What began as a search for compost evolved into an enterprise processing food scraps, dairy and horse manure, coffee chaff and wood chips.

Molly Farrell Tucker

BioCycle May 2012, Vol. 53, No. 5, p. 18

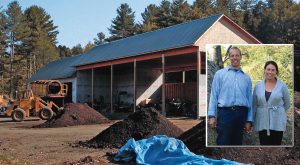

Scott Baughman and Lisa Ransom (inset) started Grow Compost in 2009. A 5,000 sq. ft. compost barn is used to store finished product and bagging equipment.

Baughman and Ransom always used compost in their vegetable and flower gardens on the farm and found it difficult to find compost for their organic gardens. “After doing some research, Scott and I learned that 30 to 50 percent of the materials going into the landfill were nutrient-full organics,” says Ransom. “It seemed so wasteful for those nutrients to be thrown away rather than returned to the soil. We felt moved to change the dynamic of waste in our community.” The couple decided to open a composting facility on seven acres of their land.

Ransom and Baughman completed a five-day composting course at the University of Maine Compost School in Monmouth, Maine in October 2008. That fall, they also met with the Vermont Agency of Natural Resources’ Act 250 coordinator in District 5 (the permitting agency), several specialists from the Vermont Agency of Agriculture, a representative from the Natural Resources Conservation Service, composting experts from the Highfields Center for Composting and the administrator of the Mad River Resource Management Alliance, which manages solid waste facilities in seven Vermont towns including the Moretown landfill. “They came to our site and all of them said it sounded like a good idea,” recalls Ransom. The Highfields Center helped Ransom and Baughman develop their first management plan and define which method of composting to use, what equipment was needed, and how to deal with the space constraints.

Obtaining financing was close to impossible, says Ransom. “Financing was and continues to be very tight. Banks are not familiar with the particularities of composting. We were teaching them about the industry as we were learning business practices ourselves. We pieced together financing from banks, friends and family.”

The permitting process was also difficult. “The permitting issues around compost were very unclear in Vermont,” says Ransom. “We knew that we would need to obtain all of the possible permits that were, or could some day, be required,” adds Baughman. They made a point of talking to all of their neighbors, including the landfill. “The neighbors have lived next to the landfill for more than 20 years and there are similar concerns with composting, such as traffic, vectors and odors,” she says. There was no opposition to the permit.

Their company, Grow Compost of Vermont, was registered with the State of Vermont in December 2008. They started site work in fall 2009 and Baughman began collecting food scraps and farm residuals. The first batch of compost was ready for sale in late fall 2010.

Grow Compost was the first composting facility in the state to receive an Act 250 Land Use Permit. (Act 250, known as the Land Use and Development Act, established nine District Environmental Commissions to review large-scale development projects to ensure that they meet 10 criteria designed to protect the environment, community, and state of Vermont.) “Scott and I knew we needed the Act 250 permit even though the state hadn’t clearly defined the parameters of the Act,” says Ransom. This spring, the state of Vermont adopted new composting regulations, creating three classes — small, medium and large. “We are now classified as a ‘medium size’ facility,” she adds. “Because we had obtained all necessary permits ahead of the new regulations, we were fully compliant with the new rules.”

Requirements for medium-size facilities are as follows: 1) Have a compost management area of less than 10 acres in size and 2) Compost the following materials: a) More than 10,000 cubic yards (cy)/year of leaf and yard waste; or b) Compost 40,000 cy/year or less of total organics of any of the following feedstocks: not more than 5,000 cy/year are food residuals or food processing residuals and not more than 10 tons/month of animal, animal offal and butcher waste.

Feedstock Sources And Collection

The facility composts farm waste as well as food scraps from restaurants, schools, businesses, hospitals, prisons, elder care facilities and local residents. All of the feedstocks come from within a 20-mile range of the facility. Grow Compost hauls some of the food scraps to the site in totes, and uses a “hook truck” to collect containers of manures and other bulk organics. The Central Vermont Solid Waste Management District (CVSWMD) Organics Program also brings materials to Grow Compost. CVSWMD collects organics for two other composting facilities in central Vermont — Vermont Compost Company, and the Highfields Center — using a truck with a tote washing system.

Grow Compost receives over a ton/week of food scraps (the equivalent of about one hundred 48-gallon totes containing 220 pounds/tote) from more than 75 generators. More comes during the winter months because the CVSWMD truck collects from resorts, restaurants and schools in the ski resort towns of Stowe and Sugarbush. Friends and neighbors also bring their residential food scraps to the composting facility. “The stream is very clean,” notes Ransom. “We do lots of training, so we don’t even get a tote’s worth of garbage in a week.” Grow Compost does not accept biodegradable bags or PLA-based compostable products.

Baughman collects manure, silage and hay from eight local dairy and horse farms. “Dairy manure with bedding is the only input that we pay for,” says Baughman. “It is a clean, consistent source of material.” The company doesn’t pay for horse manure and receives a tip fee for the food scraps. Its two main sources of carbon come in together — five to seven tons of burlap bags each week filled with coffee chaff, the skins from coffee beans, from Green Mountain Coffee Roasters’ plant in Waterbury, Vermont. “The chaff has the consistency of sawdust and is a good source of nitrogen,” Ransom says. “The burlap bags are shredded and added to the windrows and provide a slow release of carbon. We have worked closely with local coffee roasters to establish a clean stream of burlap free of nylon strings.”

Grow Compost also receives free wood chips from tree services. “A lot of trees came down during Hurricane Irene last summer,” notes Ransom. “We are in a wonderful location on Route 2 and the tree service trucks are going back and forth all the time.” The wood chips are resized at the composting facility into sawdust with a Montgomery Wood Hog unit.

Transitioning To Aerated Piles

The seven-acre composting site includes a five-acre compost pad made of crushed gravel, and two barn buildings on the remaining two acres. The 5,000-square-foot compost barn is the largest of the three barns and contains finished product, space for maintaining equipment, a bagging room and a wash bay. Ransom and Baughman plan to build an aerated static pile (ASP) system in half of the main building in fall 2012. Grow Compost received a Vermont Community Loan Fund Technical Grant and Vermont Housing and Conservation Farm Viability Implementation Award to design and engineer it. “We hope that the ASP system will recover energy and some heat, in addition to allowing a larger throughput,” explains Ransom. “We’re trying to design it to be open to whatever the technology of the future brings.”

The facility has two seasonal employees, as well as Baughman’s father Dick Baughman, who works 30 hours a week. Baughman focuses on the composting site and production and Ransom is in charge of bookkeeping, sales, marketing and running the retail shop. Grow Compost produced 4,000 cy of finished compost in 2010 and 6,500 cy in 2011. “With the aerated static pile system installed, we hope to produce over 10,000 cy/year by 2015,” notes Ransom. Inputs are increasing. “Our intention has never been to become a mega facility,” says Ransom. “Act 250 stipulates how much land can be used for this purpose. Our goal is to use our land for its best purpose and we believe that producing compost is the best use.”

Compost and soil blends are packaged in reusable garden bags in 20- and 40-quart sizes. The bagged compost is sold in retail stores, garden centers, co-ops and specialty shops.

All of the equipment at Grow Compost is vintage, and many pieces run on vegetable oil, which Baughman collects with the food scraps. Baughman retrofitted a chip recovery plant from Keene, New Hampshire into a screener. “It’s all been a challenge but also exciting, wonderful and fun,” Ransom says.

Molly Farrell Tucker is a Contributing Editor to BioCycle.