An extensive data collection undertaking has yielded an improved picture of wastewater treatment plants in the U.S. with operating anaerobic digesters and if and how the biogas generated is utilized.

Maile Lono-Batura, Yinan Qi and Ned Beecher

BioCycle December 2012, Vol. 53, No. 12, p. 46

How many wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) have anaerobic digestion? How many are utilizing the biogas? What percentage of these facilities are feeding additional substrates into their digesters? How is the biogas being used — is it flared, used to drive process machinery, heat the digester, or injected into a natural gas pipeline? These are some of the questions asked of the approximately 1,200 wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) currently operating anaerobic digesters across the United States during a survey conducted in the fall of 2011 and winter and spring of 2012. With seed funding from the Water Environment Federation (WEF), the North East Biosolids & Residuals Association (NEBRA) and Black & Veatch led a team of approximately 20 industry representatives to gather data, state-by-state, for what has become a free online database of biogas production at WWTPs.

Preliminary results of this survey were unveiled during the Northwest Biosolids Management Association’s (NBMA) 25th Anniversary BioFest in late August 2012; more complete data were presented at BioCycle’s 12th Annual Conference on Renewable Energy From Organics Recycling in late October, shortly after the launch of the new website created specifically for this project: www.biogasdata.org. The current initial website, version 1.1, was supported by Cambi, the New York State Energy Research & Development Authority (NYSERDA), and the National Biosolids Partnership and produced by 350 Technologies LLC.

The data gathering and resulting website are intended to provide policymakers, market analysts, project developers and water quality professionals with key information about the potential for biogas production at WWTPs as a renewable fuel. Biogas can be used in place of natural gas in boilers and engines to produce heat and electricity in combined heat and power (CHP) systems. “The goal was to develop and present a consensus-driven data set — data that everyone in the field could rely on,” says Lori Stone, Global Practice and Technology Leader at Black & Veatch, one of the principal investigators on the project. “It took hundreds of phone calls to wastewater treatment facilities to ensure the accuracy of the data. The teamwork made the daunting task more manageable.” In addition to NEBRA and Black & Veatch, the core project team included the Mid-Atlantic Biosolids Association (MABA), American Biogas Council, California Association of Sanitation Agencies, NBMA and BioCycle, with help from engineers at HDR and Hazen & Sawyer.

The Need for Better Biogas Data

There are four major sources of biogas production: landfills, farm digesters, industrial facilities (e.g. food processors such as Stonyfield and Tropicana) and WWTPs. In recent years, data have been compiled and reported regarding two of these sources: U.S.EPA Landfill Methane Outreach Program (LMOP), which tracks projects using methane from landfills across the U. S. (594 operational projects as of June 2012; www.epa.gov/lmop/); and U.S.EPA AgStar program, which provides information on farm-based digestion projects (an estimated 192 as of September 2012; www.epa.gov/agstar/projects/index.html.

But information on industrial digestion projects is difficult to compile, in part because of proprietary information. And, until now, estimates of biogas production at WWTPs have been only approximate. For example, in 2007 and 2011, the U.S.EPA-led Combined Heat & Power Partnership reported its estimates of biogas production and potential from the nation’s WWTPs, which was the best information available at the time. According to its analyses, as of June 2011, “CHP systems using biogas were in place at 104 WWTFs, representing 248 megawatts (MW) of capacity.”

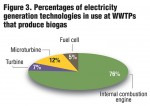

While further data analysis is needed to understand what the new www.biogasdata.org data can add to improving this kind of information, it is at least clear from this most recent undertaking that there are nearly 300 electricity generating systems in operation at WWTPs in the U. S., most of which involve utilization of heat (i.e., are CHP systems) — far more than EPA had estimated. Project team members noted that even EPA’s estimates of the number of WWTPs with operating anaerobic digesters seemed to be low.

Compiling the Data

The biogas data project started in the fall of 2011, with $25,000 from WEF and a spreadsheet of WWTPs with AD, donated by InSinkErator. The company had hired a summer intern to check websites of WWTPs greater than 5 MGD, to confirm if they had operating AD; 858 were confirmed (although some of these data later proved wrong as websites are often not up-to-date). Conference calls were held with the project team and an advisory group convened by WEF in order to reach consensus on what data were to be collected initially (Phase 1 data) and what the “wish list” for additional data might contain.

An initial online database into which project team members could enter data was created. Over the next eight months, the project team worked to confirm the list of all WWTPs in their assigned state(s). The data collection protocol included these steps:

1. Contact the regional U.S.EPA biosolids coordinator and/or the state biosolids coordinator and obtain any data they may have. It is rare to have lists of AD facilities, but sometimes there are lists of all WWTPs in the state, with critical contact information. Also inquire about other people in the state who may be familiar with AD facilities at WWTPs (e.g., consulting engineers).

2. Using the list in the initial online database which indicated which WWTPs were thought to have AD, start calling the largest of the facilities, not only to obtain their data, but also to see if they know about other AD operations in the state.

3. Continue calling all WWTPs thought to have AD, to confirm and collect data about what they do with the biogas (Phase 1 data). Also contact all or some of the largest facilities thought not to have AD, to confirm. The data collectors thus built an understanding of AD and biogas use in each state.

4. For a few states, project team members contacted all facilities greater than 1 MGD or greater than

5 MGD, including those with AD and those without AD. Thus, the level of confidence in the final data from such states is very high. Other data collectors went only so far as to confirm

the complete list of WWTPs with operating AD.

5. As a final data check, the final list of AD facilities was shared again with one or two experts in the state, e.g., the biosolids coordinator, to ask if they could think of additional facilities that have AD or saw any errors.

6. Each data collector provided notes on their particular data collection process for each state and estimated the level of confidence they had in whether or not they had compiled a comprehensive listing of facilities with AD. These notes are compiled in a spreadsheet.

This process was built on the years of experience BioCycle and other team members have had in compiling data. Despite the hopes for a simpler, more efficient process, the reality remains that, in this field where reporting by biogas project managers is not required, quality data can only be obtained through direct contact with facilities.

The data being collected was deliberately basic. The consensus was that it is better to have comprehensive, complete data regarding basic details rather than collect partial data on many different details. Thus, the primary interest was to determine which WWTPs have operating digesters and/or send their solids to AD. For facilities with operating AD, the Phase 1 data collection effort included: Facility contact information; Average daily and design flows; Type of digestion (e.g. mesophilic); Whether or not outside waste was being fed directly into the digester(s); How the gas is managed (e.g. flared, for heat, for electricity, etc.); and Basic type(s) of technologies used for power generation, if any. While the project team and advisory group wished to request more data, such as actual biogas production volumes, adding additional fields to the data collection process would have extended the project months more. As noted below, there is a need for “Phase 2” data collection.

Results

The data compiled by this project and presented at www.biogasdata.org positively confirmed that the wastewater solids (sludge) from more than 1,238 or more U. S. WWTPs undergo anaerobic digestion (AD) and produce biogas. Almost all of this wastewater biogas production occurs at facilities that treat from one to hundreds of millions of gallons per day (MGD) of wastewater. Most of these plants have their own operating AD systems, but some send their solids to another WWTP where they are processed by AD. Table 1 lists the number of WWTPs in each state with operating AD and/or that send their solids to AD.

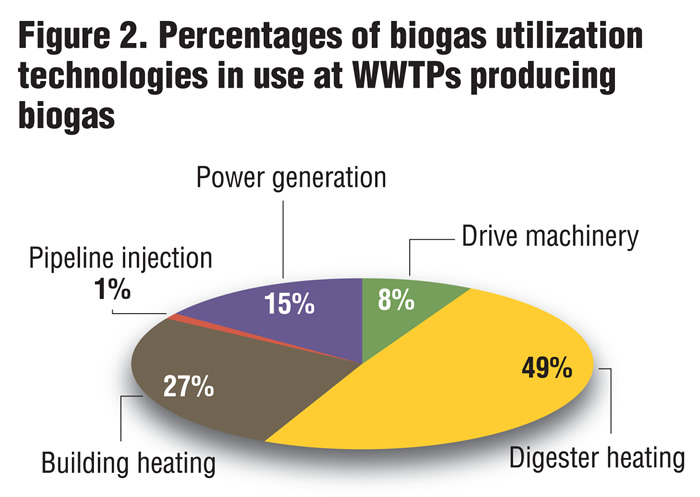

The figure also depicts the relative level of uncertainty ascribed to the data from each state. For several states, the project team is 100 percent certain that it has the complete list of AD facilities — it’s easy for states like Alaska and Maine, which only have one each. For other states, the level of certainty is lower, as indicated by the length of the red bars at the top of the graph. For example, data for Maryland and Texas are particularly limited and should be considered with a grain of salt. Future efforts are planned to improve the data in these and other states for which the confidence is lower.

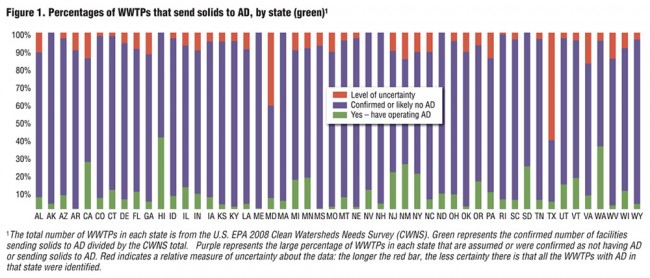

The known number of WWTPs with AD (and/or that send solids to AD) allows calculation of clear percentages regarding how the biogas is put to use (Figures 2, 3). In terms of whether or not surveyed facilities feed outside waste into their digesters, the data indicate that 17 percent receive substrates from off-site that are fed into their digesters.

The Potential

The data also sheds light on what is not being done. Nearly two-thirds of the 3,200 major WWTPs in the U. S. (those greater than 1 MGD) do not send solids to anaerobic digestion and produce biogas. In addition, there are almost 12,000 minor facilities (less than 1 MGD in size), and only a small number of these operate anaerobic digesters. While efficiencies of scale are important, there are some minor facilities successfully producing and utilizing biogas, and smaller size AD facilities are common on farms and in other situations. There is clearly potential for considerably more biogas production from wastewater.The use of biogas at WWTPs is also underdeveloped. The data show that one-third of the treatment facilities that produce biogas do not put it to use for energy, and more than 870 are flaring at least some of the biogas produced. (Several WWTPs contacted noted that they release biogas directly to the atmosphere; the methane contained in it is a greenhouse gas with more than 21 times the warming impact of carbon dioxide.)

Looking Ahead

The new website database, www.biogasdata.org, will continue to undergo minor enhancements to improve how the data is presented, sorted and reported. An additional report on the Phase 1 data should be available for download from the site by year’s end. Further significant additional functionality of the website, including finalizing full editing, data review and approval, administration, and data validation systems, is on hold, pending further planning and funding. Additional reporting features, including downloading to CSV files, is also planned, if and when the project continues.

A Phase 2 of the data collection project would include, for example, measured or estimated total biogas production at each WWTP, details about types of technologies in use for biogas treatment and energy production, existence of decommissioned digesters, local cost of electricity, etc. Other biosolids management data (e.g., technologies used, use or disposal practices, etc.) and inclusion of data from other countries in North America could be included as well.

Maile Lono-Batura is Executive Director of the Northwest Biosolids Management Association (NBMA), Seattle, WA; Yinan Qi is a Project Engineer with Black & Veatch, Kansas City, MO; and Ned Beecher is Executive Director of the North East Biosolids and Residuals Association (NEBRA).