Here are tips for how composting facilities can design their own odor characterization tool.

Katrina Mendrey

BioCycle February 2014

According To Michael McGinley, Laboratory Director at St. Croix Sensory, Inc., the only bad odor wheel is the odor wheel that isn’t used. “It’s a powerful tool for knowing your facility inside and out,” he notes. “But it’s also a simple tool and doesn’t require a consultant.” Odor wheels were originally developed for the wine industry by researchers at the University of California Davis. The concept of an odor wheel is that smells are organized categorically to help the user move from the broad, e.g., sweet or putrid, to the specific.

At composting facilities, odor wheels can help staff identify odors to respond to complaints or identify when there might be an issue with a specific pile or process. “The odor wheel is an important part of getting to know your facility and sources of odors,” says McGinley. “That way over time you get to know if something has gone awry. If you’re getting complaints you can look around your facility and get an impression if things seem different or if people are complaining about different characteristics. You can identify better what might be the source of those smells.”

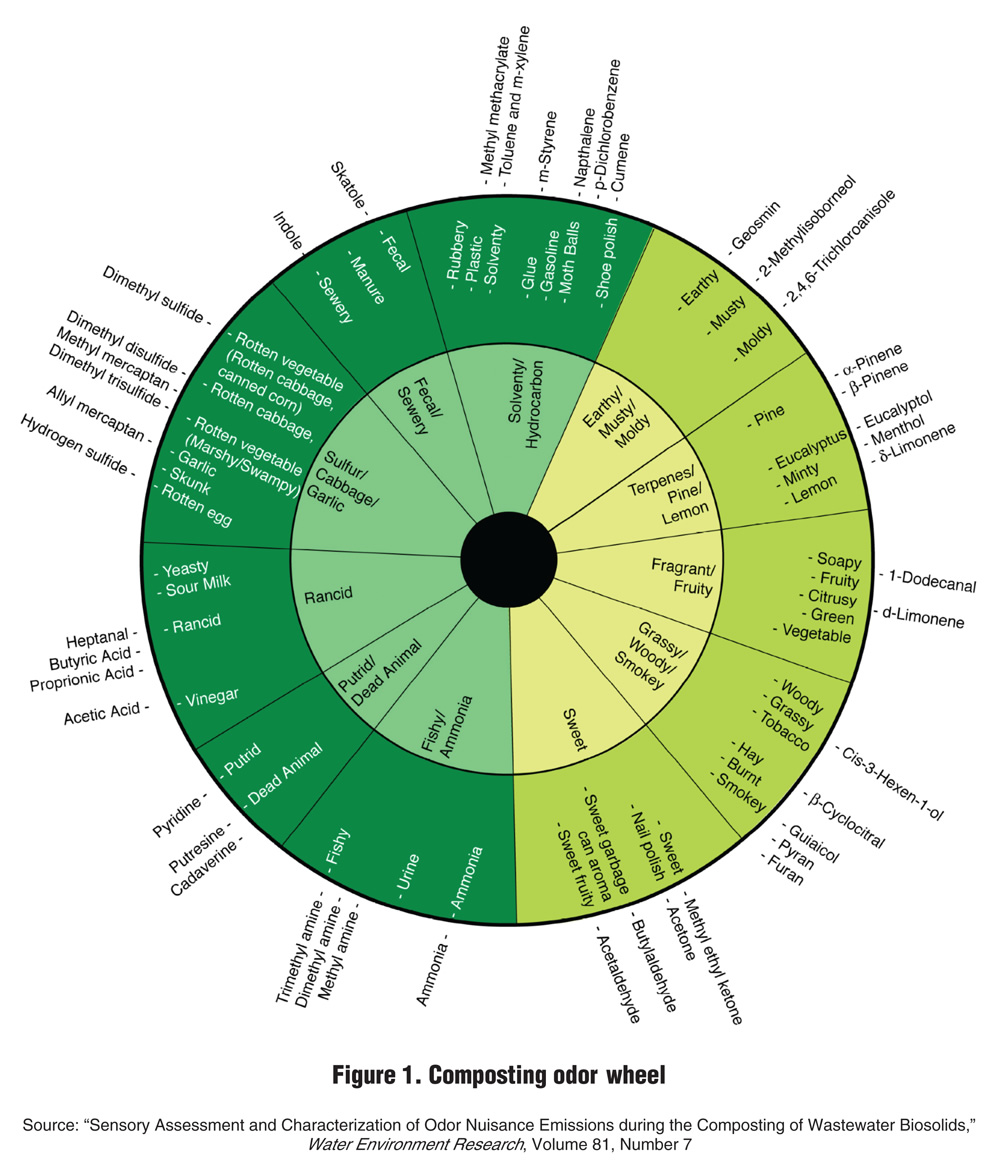

Figure 1. Composting odor wheel Source: “Sensory Assessment and Characterization of Odor Nuisance Emissions during the Composting of Wastewater Biosolids,” Water Environment Research, Volume 81, Number 7

Existing odor wheels for composters offer a good starting point for developing a facility specific wheel. St. Croix has a basic wheel of odor descriptors (available at www.fivesenses.com) that use broad categories such as “Fishy” or “Earthy” to then describe more specific smells like ammonia or yeast. A compost specific wheel, such as one developed by I.H. (Mel) Suffett, Ph.D. at UCLA (Figure 1), uses compound names as the final descriptor to identify smells.

Customizing An Odor Wheel

The process for making a customized odor wheel for a composting facility is iterative and inclusive. McGinley suggests beginning in a conference room where staff can brainstorm odors they know they have smelled. Step two is to go out into the facility to identify odors. Taking it a step further, sampling piles using a glass jar or plastic bag, can be a helpful way of isolating odors for better characterization in an odor neutral area. Once odors have been categorized, they can be further characterized by classifying their strength using an agreed upon scale (i.e., 0- 5 or “undetectable to unbearable”) or identifying if there are multiple odors present based on the more specific categories provided by the wheel.

“Ultimately your goal for the final product is something that can be used by everyone and that creates a common language for your facility to identify and discuss odors,” explains McGinley. Once the group has identified smells and categorized them into an odor wheel or table, the next step is to use it. “Don’t let the process go stagnant,” he adds. “Update the wheel when new odors are identified and to train new employees on how to use it.” One way he suggests doing this is to incorporate the wheel into daily routines, such as when checking pile temperatures.

Odor wheels can also be helpful when paired with other odor measurement devices such as the Nasal Ranger®, a hand-held field olfactometer that measures Dilution-to-Threshold values of ambient odors associated with a facility. The odor wheel will help characterize the odors measured more specifically, notes McGinley.

In addition, odor wheels can be helpful tools in community outreach. Providing neighbors with a way of communicating bothersome smells in a language that can be understood by the composters allows for more effective management of odors onsite. This also gives neighbors a sense that they are being heard. McGinley cautions, however, that composters should not give neighbors odor wheels unless they plan on actively engaging them in the odor monitoring process.