Dan Sullivan

Related article in this issue: DuPont Label Says “Do Not Compost” Grass Clippings

Related article in this issue: DuPont Label Says “Do Not Compost” Grass Clippings

The active ingredient was aminopyralid, developed and marketed by Dow AgroSciences in products bearing various brand names including “Milestone” and “Forefront.” A Whatcom County, Washington, extension agent told BioCycle that label restrictions limiting the off-farm export of manure from farms on which the herbicide had been applied presented challenges, particularly in regions where dairy farms are not large enough to land apply all the manure they produce.

Milestone’s label states: “Do not spread manure from animals that have grazed or consumed forage or eaten hay from treated areas within the previous 3 days [of application] on land used for growing susceptible broadleaf crops.” That label goes on to explain that such manures may only be safely applied to pasture grasses, grass grown for seed and wheat and warns: “Do not plant a broadleaf crop in fields treated in the previous year with manure from animals that have grazed forage or eaten hay harvested from aminopyralid-treated areas until an adequately sensitive field bioassay is conducted to determine that the aminopyralid concentration in the soil is at a level that is not injurious to the crop to be planted.”

Problems began to emerge when farmers and gardeners in northwestern Washington state used compost made with manure from farms on which aminopyralid had been applied (one farmer reported more than $200,000 in crop losses). Dow officials said there would not have been a problem had the label directions been followed. Problems with aminopyralid were also reported in North Carolina in 2008, the same year Dow voluntarily suspended sale of the herbicide in the United Kingdom (UK) after backyard and community gardeners reported plant damage from tainted compost. After it was reintroduced in certain parts of the UK last spring with tighter manure-management restrictions in place, continuing problems seemed to indicate that the herbicide had remained persistent in the previous year’s manure piles.

Ongoing Problems

Ongoing Problems

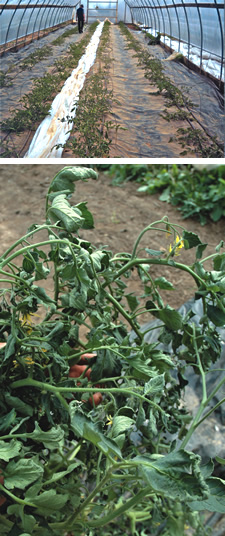

During reporting for the accompanying article on Imprelis, BioCycle happened across a commercial composter as well as a farmer who worked manure from a single horse into the soil in two hoophouses. Each reported experiencing problems with aminopyralid. The composter declined to go on the record because he was concerned about jeopardizing his organic certification. (Whether it’s an accident or not, if an agricultural operation becomes contaminated with an unapproved synthetic chemical, that portion of the facility may be required to undergo a three-year recovery period before it can be recertified for organic production.) Elvin Burkholder, a Pennsylvania Mennonite who says he farms as organically as he can manage but is not certified, agreed to this interview but was unable to disclose specifics of his settlement with Dow. Burkholder, owner of Shady Acres Produce in Fleetwood, Pennsylvania, lost two hoophouses full of tomato plants and now must figure out how to amend or replace the soil in both of them. (A hoophouse is a greenhouse with a plastic roof stretched over flexible piping.)

“Some seedlings grew surprisingly much and then started growing a tip curl,” Burkholder says. “They didn’t snap out of it.” Fortunately, he never got around to working the horse manure into a third hoophouse and has other producing structures to see him through. “I bought hay at the auction, fed it to my horse and put the manure in the barn,” Burkholder says, adding that he purchased hay in spring 2009 that had been cut the previous year and fed it to his horse into that winter. He says he continued to stockpile horse manure in his barn until he was ready to work it into the soil in his hoophouses this spring. “I took the manure out of the barn, piled it up by the greenhouses and two or three weeks later worked it into the soil; it was not really heated or composted.”

Once crop problems surfaced, Burkholder investigated and found that the hay he’d purchased in 2009 had been sprayed with Forefront, which contains the active ingredients aminopyralid and 2,4-D.

Once crop problems surfaced, Burkholder investigated and found that the hay he’d purchased in 2009 had been sprayed with Forefront, which contains the active ingredients aminopyralid and 2,4-D.

Dow came out to the farm and took samples of the soil, the green fruit and the plant, which were sent to a lab. “I was surprised the soil came back showing nothing – they only took three probes,” he explains. “What I’ve heard is that it [aminopyralid] doesn’t move around much in the soil. The fruit came back with nothing, which surprised me because it deforms the fruit, and the plants showed 2.1 parts per billion. Some of the worst plants were really stunted; they got a foot high and just sat there.” The better plants grew high but did not have good foliage, he adds. “The flowers looked normal, but the fruit deformed when it was green with a small nibble that got bigger. It doesn’t look like a tomato but an upside-down pear.”

Without going into detail, Burkholder says Dow’s either/or offer of compensation won’t cover his losses. “I had been told they would either reimburse some of the costs or change the soil. I told them I’d like to change the soil, but if I don’t get reimbursed for my losses this season changing the soil won’t help.”

“The way I understood it, the label says the grower should have told me he was using it on his hay. If the grower would have told me I would have said, ‘What’s that?’ What I was told by Dow is that they are not actually legally responsible for it.” Burkholder says he’s heard of other growers in nearby Lancaster County experiencing difficulties with tomatoes, soybeans and alfalfa hay that sound suspiciously like the problems he’s been experiencing.

Amended Label

Dow AgroSciences spokesman Garry Hamlin explains that the company has amended its federal labeling to address compost- and manure-related challenges and has provided supplemental labeling for grower access in certain states to address unique agricultural practices in various regions. “What we find is where you have a concentration of confined animals – that typically means a dairy, but it can mean other things – you can have problems in this arena,” explains Hamlin. “In essence, this situation is addressed by new federal labeling that prohibits moving treated hay off-farm.”

In certain areas, where density of confined animals is less of an issue, growers can get supplemental state labeling that does allow them to move hay off-farm, says Hamlin. But the supplemental labeling is a special case and is not available to growers in many states. For instance, it is not available in Washington State – where, Hamlin says, moving hay off-farm could cause problems because of the type of agriculture practiced there. The federal label is what appears on the container – the supplemental labeling does not – and in states where the supplemental labeling is not authorized, moving hay off-farm is not allowed.

What that boils down to in Washington state – and other states where farms have large numbers of animals but not enough land to manage a closed-loop system – is limited use of the product. “We have prohibited use other than on standing pastures,” says Hamlin. The situation was similar in the UK, he adds. “UK agriculture is very different than what we find in the U.S. We asked the UK government if we could withdraw the product until we could revise labeling to preempt these types of things from occurring. The product has been available for sale in the UK since last year. There have been some issues with manure produced under the previous label, but by and large those issues are done.”

What that boils down to in Washington state – and other states where farms have large numbers of animals but not enough land to manage a closed-loop system – is limited use of the product. “We have prohibited use other than on standing pastures,” says Hamlin. The situation was similar in the UK, he adds. “UK agriculture is very different than what we find in the U.S. We asked the UK government if we could withdraw the product until we could revise labeling to preempt these types of things from occurring. The product has been available for sale in the UK since last year. There have been some issues with manure produced under the previous label, but by and large those issues are done.”

The label on agricultural products containing aminopyralid now also includes a pictograph (see page 4). “We said ‘Okay, fine, we’re going to draw you a picture,'” says Hamlin. It comes down to a matter of both following directions and asking the right questions, he adds. “If someone is getting free manure from their neighbor as an uncharacterized input and nobody has asked any questions, you may have a problem. If you’re getting hay from someone who didn’t read the label, you may have a problem. And unless you know about the supplemental labeling and are in an area where it actually applies, you can’t use this product if you’re going to be cutting hay and moving it off-farm.”

“We looked at a similar situation with hay and clopyralid many years back. We worked with the hay growers associations; they very much felt a need for the product and understood that if it was not used in an approved way, they were not going to have it. The problem was successfully dealt with not only because of sound regulation and sound labeling but also because we had key users who valued the product and were committed to using it the right way. The hay growers were very focused in working with us; they didn’t want it to be an issue.”

For Pennsylvania Mennonite farmer Elvin Burkholder – whose business card for Shady Acres Produce boasts “Fresh, Local, Nutritious, Chemical-Free” – the unwelcome guest aminopyralid continues to be an issue. “I told [Dow officials] they shouldn’t be allowed to sell it and that I thought they had to prove that it was safe,” Burkholder told BioCycle. “They said the EPA approved it as safe if it’s used according to the label. They might call that safe, but I don’t. It kind of woke me up.”

Related articles from the BioCycle Archive:

- Dow Restricts Use Of Aminopyralid, March 2011

- Persistent Pesticide As Organics Recycling Foe, August 2010

- Composters Off Bifenthrin Black List, May 2010

- Certified Organic Compost Under The Gun In California, March 2010

- Clopyralid Levels Decline, But Controversy Continues, May 2004

Mother Earth News: Keep your garden safe from killer compost