Nate Clark

Compost Pedallers “burn calories instead of fossil fuels,” a motto that speaks to its core principle of strictly using the bicycle to transport food scraps. Photo courtesy of Compost Pedallers

Community-scale composting has become somewhat of a buzzword in the organics recycling industry. At its core, community-scale composting is the notion that organics are processed as close to the sources where they are generated to capture the benefits of both the process and the finished product for the community. In practice, that can take many different shapes, from composting in the backyard to composting operations in or near the community it services, with all or a portion of the finished compost returned back to the community for food production, storm water management, soil remediation and more. Community-scale composting also encompasses collection services that facilitate organics diversion in their community. These operations have been effective in engaging citizens in the organics recycling process.

Community-scale composting is often perceived as having limits to its processing capacity, growth, equipment use, etc. Increasingly, however, these composters and collection enterprises have developed innovations to provide their service to as many members of their community that wish to engage with them, no matter the size of that community. This article highlights three innovative companies that have developed tools to enhance their businesses’ ability to service more generators, divert larger quantities of organics, engage more citizens and, overall, help make their communities more resilient.

Yard sign outside the Blue Dahlia Bistro indicates the restaurant is a composting subscriber (top). Ray Mitrano, a Compost Pedallers staff member, weighs a collection bin before emptying to calculate “Your Impact” and Loop points (bottom). Photos courtesy of Compost Pedallers

Compost Pedallers

Austin, Texas

Dustin Fedako has been communicating the benefits of composting for years. “While I was applying to graduate school, I had a job as a door-to-door salesman for a residential composting service,” Fedako explains. “I would talk to thousands of people about waste and the amount that can be diverted through composting, and I was surprised by the amount of people living in Austin (TX) that were either not composting, or didn’t even know what composting is.” Austin has a reputation as a progressive city, exemplified through its “2040 zero waste goal” established in 2011. Fedako didn’t understand why, despite the growing demand for waste diversion, so many people still weren’t composting.

“What I came to realize is that there is not really an affordable and convenient solution for composting here in Austin,” Fedako recalls. “I started dreaming up what my ideal composting program would look like: It would be simple and engaging, motivating people to participate because they enjoy the process — instead of making it a chore that they have to do.”

From this dream, Compost Pedallers, a subscription-based residential and commercial food scraps collection service, was born in December 2012. Residential subscribers sign up online, and within one week, receive a starter kit that includes source separation training materials (i.e., flyers and refrigerator magnet stating what is/is not compostable) and a 5-gallon collection bin. Residential subscribers are serviced once a week, and are asked to leave their bin on the front porch or step. “It is a valet-style service,” Fedako explains. Bins are washed before being returned to residents.

Prior to beginning service, interested commercial subscribers receive a free consultation and waste audit so Compost Pedallers can get an understanding of the organization’s waste stream. “This enables us to set up a food scraps diversion program that is customized to the organization and fits its needs,” he says. When a commercial entity signs up for service, it is provided training materials (similar to residential customers) to hang in the kitchen and/or office. Compost Pedallers also conducts source separation training for employees who work with the food, along with any other staff. Commercial subscribers are given 5-gallon collection bins or a “Slim Jim” tote for inside collection, and 32-gallon roll cart(s) to deposit material into outside. Compost Pedallers currently services just over 500 residential and 50 commercial customers, and has diverted around 250,000 lbs of food scraps from the landfill since it started two years ago.

Materials are pedaled from the point of collection to the nearest “CompHost” — anyone in the Austin community who is interested in growing food or growing soil, and has the ability to process a certain volume of organic material through composting. “A ‘CompHost’ can range from a 3-acre commercial urban farm to somebody who is harvesting worms in their garage,” explains Fedako. Currently, Compost Pedallers partners with almost 30 gardens and farms. The company intends to grow that number as the subscriber base grows. Taken together, this network of “CompHosts” is referred to by the Compost Pedallers as the “Organic Smart Grid”. “Austin is becoming the ‘silicon hills’, with tons of tech companies locating here,” he adds. “People understand things in terms of smart grids, and we wanted to play on that in a fun way.” Compost Pedallers is in the beta testing phase for a proprietary technology that will help monitor its growing network of “CompHost” sites using smart phones and QR codes.

Innovative Customer Benefits

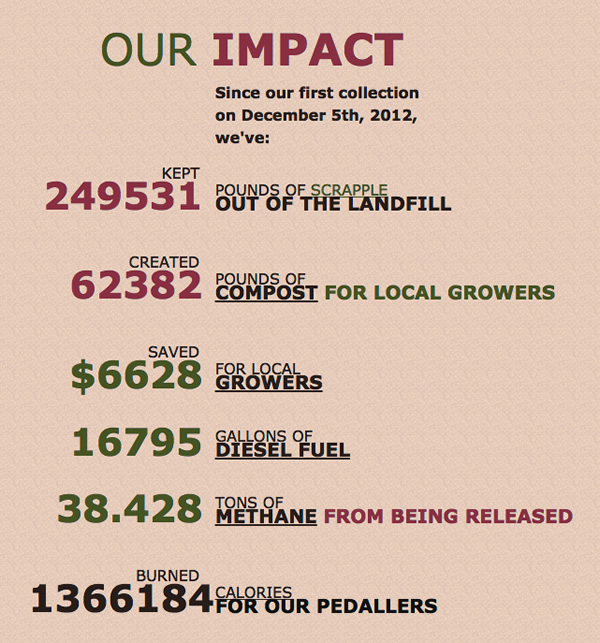

To encourage participation in food scraps diversion programs and organics recycling in general, proponents tend to hail the environmental benefits of these practices over sending the same material to the landfill. But when a household or business subscribes to a food scraps collection service, these benefits aren’t always apparent. To remedy this situation, Compost Pedallers has developed a tool to do just that. All subscribers have a profile that they can log into on the company’s website. During collection, containers are weighed before being emptied, and that weight is added to the subscriber’s profile. Once signed in, the customer has access to a section titled “Your Impact.”

Compost Pedallers tracks individual (via Your Impact data tracking) as well as the collective “Our Impact” that the business has had since opening. “Scrapple” is the term used for the food scraps collected.

“The Your Impact webpage gives individual subscribers statistics on how many pounds they have diverted to composting; how many pounds of finished compost that equates to; the amount of money that compost saves local growers; the amount of methane diverted from the atmosphere as a result of their participation; and how many calories that they have burned for a Compost Pedaller,” explains Fedako.

“We want to give subscribers a real-time score card to track their own progress, compare it with friends, and share that impact with other people.” He notes that Your Impact is especially beneficial for commercial customers. “With our commercial customers, we often work with the Director of Sustainability [or someone with a similar title], and they are always looking for more compelling ways to tell the company’s story of sustainability,” he adds. “Your Impact is a very concrete way to do that.”

But Fedako started the Compost Pedallers with the goal of making composting accessible to everyone, knowing that not every citizen cares about methane reduction and sustainable food production. “There are a number of people that we talk to about our service and its benefits, and when we get to statistics about climate change and other issues, their eyes glaze over,” says Fedako. “We wanted to find a way to engage those people as well.” He started with a compost give-back program that many food scraps collection companies practice, but found a number of subscribers don’t have a need for compost. “We went back to the drawing board, and this led to the idea of offering rewards,” he adds. “‘The Loop’ is what we came up with.”

The Loop is a point per pound rewards program — one point per pound of food scraps. When subscribers log into their profile on the Compost Pedallers website, they have access to the online Loop Store, which has free goods and deals from local businesses that are offered for a set amount of Loop points. Twelve businesses currently participate, and there is a waiting list of additional businesses interested in joining. Offers include a free cup of coffee (8 Loop points), one week of yoga (135 Loop points), and even a free bicycle (750 Loop points). “The Loop changes the way we interact with customers who are less environmentally-inclined,” notes Fedako. “It changes the conversation from methane to a free bicycle, free food, free groceries. Our goal is to utilize these types of offerings to reel customers in, and once they have experience with the program over time, help them to make the environmental connections. We are a gateway drug into a more sustainable lifestyle.”

In addition to encouraging subscriptions with the Compost Pedallers, The Loop also supports the local economy by driving traffic into local businesses participating in The Loop. “In exchange for offering free or discounted goods/services, Loop partners receive the marketing value that comes from the exposure of putting their business in front of our growing membership,” explains Fedako. “Compost Pedallers’ subscribers are 500 of the ideal customers for these businesses, and we also highlight partners on our website and social media.”

Gainesville Compost’s custom-built scrap hauling trailer includes a dumping mechanism to assist staff with lifting full totes that can weigh upwards of 200 lbs. Photo courtesy of Gainesville Compost/Kanner Karts

Gainesville Compost And Kanner Karts

In 2011, Chris Cano was a year out of college, and spending a lot of time in the garden at the home he shared with friends in Gainesville, Florida. “It was a small area, but I was learning to grow a lot of food and getting excited about growing food,” Cano remembers. “I would have friends over for dinner all the time, sharing the produce I harvested, and it was a meaningful experience. Part of this experience was making compost from our own kitchen waste. It really amazed me how you can turn waste into fuel for a garden.”

Cano discussed his interest among friends who were chefs or employees at restaurants. “I would tell them, ‘Hey, you know what I am doing [composting], and I want to do more. Can you bring some of the kitchen waste from the restaurant so I can make more compost for my garden?’” he says. “I was selfishly motivated.” One of Cano’s friends, a prep chef, would deliver the kitchen scraps via a bike and trailer. “I had two reactions to this: 1) A disturbing feeling about how much waste I was receiving that would have otherwise gone to the landfill, and 2) The realization of potential — what was being wasted can be valuable to the garden,” he adds. “It was obvious something could be done about it.”

In September 2011, Cano decided to take action. He started a pilot commercial food scraps collection program branded Gainesville Compost: From Waste to Food. Inspired by his friend, Cano asked to borrow the bike trailer to collect food scraps. “I made a flyer that I put on a website that explained the concept of turning food scraps from restaurants into soil to grow more food for the same restaurant, thus closing the loop,” explains Cano. “I promoted the website and sign up page by networking through friends. Five restaurants signed up for the original pilot.”

The program grew and Gainesville Compost is now a residential and commercial subscription-based food scraps collection service with over 30 residential and 20 commercial customers. Residential subscribers receive 5-gallon bucket(s) for collection, and commercial customers have the option of 32-gallon or 64-gallon tote(s) with wheels. All subscribers are serviced weekly. Collection containers are weighed prior to emptying to produce monthly waste diversion certificates to notify generators about how much material they are diverting; containers are washed before being returned.

Gainesville Compost processes all of the collected organics at numerous community composting partner locations, part of a broad “pedal powered community compost network” it has created (See “Entrepreneurs See Opportunity in Food Scraps Collection,” March/April 2014). Community composting partners include restaurants, community gardens, and other organizations that participate by hosting a composting unit on site that is managed by Gainesville Compost staff. The company currently has 10 community composting partners with plans to grow the network in 2015.

Collection Trailer Manufacturing

Customers have options when purchasing Kanner Karts, including size, color, and inclusion of a ramp with support legs to roll items directly onto the trailer. Photo courtesy of Gainesville Compost/Kanner Karts

Bicycle-based collection continues to be the food scraps transport mode for Gainesville Compost, however the design and construction of the trailers has come a long way since Cano borrowed his friend’s for the pilot in 2011. That trailer functioned but had limited carrying capacity and a weak frame. “I was only able to haul (maybe) four 5-gallon buckets at a time,” Cano notes. “I had a dream of being able to work with someone that could help me create innovations around the bike trailer aspect. I was collecting food scraps from some vendors at the local farmers’ market, and was approached by Steven Kanner, who told me he had been working on developing bike trailers for his own utility, including transporting groceries, picking up building supplies, and even once to move all his belongings from one apartment into a new home.” Cano was intrigued by the prototypes of bike trailers Kanner had posted on Facebook. “I reached out to Steven, and we started to conceptualize our first design around a food scraps collection bike trailer,” he adds.

The two cofounded Kanner Karts, which manufactures industrial bike trailers in three standard size models: 4-, 5- and 6- feet long, all 30 inches in width. Kanner also became a co-owner of Gainesville Compost. All trailers are built on a frame with 500-lbs carrying capacity. Kanner Karts buyers may add a ramp on the back with support legs to enable users to roll the items they wish to carry directly onto the trailer. “Customers have options when they purchase a Kanner Kart — even the sizes are suggestions to help make decisions easier,” explains Kanner. “We want to help people achieve whatever bike-transport ambitions they may have. If they have an idea in mind, I will work with them to see if it is viable.”

Kanner’s inclination to custom-build carts is what led to development of the Gainesville Compost food scraps collection trailer, currently the only one in existence. “What we built for Gainesville Compost is a scrap hauling, side loading trailer, with an 1.5-cubic yard aluminum tank for emptying collection containers into,” notes Kanner. “The dumping mechanism on the side latches on to totes, making them easier to lift. A full 32-gallon tote can be upwards of 200 lbs.”

The trailer has enabled the company to save money on the cost of collection containers. “Before we had to buy two containers for each restaurant subscriber, but with the tank-style cart, we just have one container on site, which we empty, clean and return during service,” explains Cano. He adds that removing one container per subscriber has resulted in less clutter at the community composting partner sites, where the filled buckets were transported. This is important in an urban setting where space can be limited. Gainesville Compost utilizes the aluminum-tank style trailer mainly for its higher-volume, commercial subscribers. “We have our logo and the logos of commercial customers on our food scraps collection trailer,” adds Cano. “It is basically a huge mobile advertisement for our business, and the businesses we service, helping us on marketing.”

Wesley Durrance, a Gainesville Compost staff member, stands next to a steel, 3-bin composting system manufactured by Kanner Karts, available at bikecompost.com. Photos courtesy of Gainesville Compost/Kanner Karts

Standard Kanner Karts are also used for collecting food scraps in containers. “When we are in a public setting (i.e. a farmers’ market) where dumping buckets can be a nuisance, we will collect containers in a standard Kanner Kart,” notes Cano. These carts have been purchased by bike-powered food scraps collection companies across the U.S., including Carter’s Compost in Traverse City, MI; Well FED Compost in Atlanta, GA; and Common Ground Compost in New York, NY.

Cano and Kanner’s unique partnership has enabled Gainesville Compost to grow, and also build a movement around bike-powered composting. Their website “bikecompost.com” provides resources for other companies interested in food scraps collection by bicycle, as well as directions on where to purchase Kanner Karts, and other tools the two develop. “We have a vision to help companies get bike trailers, and set up their own kinds of operations,” explains Cano. “Bikecompost.com is a way where we can meet others to educate and enable them to do bike-powered composting.” Kanner adds that beyond trailers, he has also developed a steel 3-bin composting system that has performed better than the pallet 3-bin systems Gainesville Compost used previously. The steel units are also available via the bikecompost.com website.

Community Composting

Rochester, New York

Steven Kraft and Brent Arnold began composting in a friend’s vacant lot, processing organics that they generated, as well as material from some neighbors and a small restaurant. When the volume of feedstock they were accepting quickly outgrew the capacity for the site, the two realized the potential value in what they were doing. “Brent and I put together a website where we asked for contact information and the question, ‘Are you interested in seeing a residential food scraps collection service in Rochester (NY)?’,” explains Kraft. “We did a small Facebook marketing campaign to direct residents to the website. Within two weeks, 350 people responded expressing interest — at that point, we knew it was a viable business.”

The idea turned into action in Spring 2013, when Kraft and Arnold launched Community Composting, a subscription-based food scraps collection service for the residential and commercial sectors. Customers are directed to sign up on the Community Composting website, at which point they are sent a welcome email that explains how to participate in the service (i.e., what materials are/are not accepted). Subscribers are given a branded 4-gallon bucket with a locking lid for collection, and an option for selecting the number of buckets and pick-up frequency. “The vast majority of residential subscribers are on a one 4-gallon bucket, weekly pick up plan,” notes Kraft. For the recently added commercial sector, Community Composting also offers 32-gallon totes. The company has over 170 subscribers, mainly in the residential sector, and has diverted over 110,000 lbs of food scraps from the landfill.

All hauling is done with a GMC 3500 Dually truck with a dump body on the back. Community Composting recently added an Isuzu NPR dump body truck with a Perkins cart lifter to service the commercial sector subscribers. Both trucks have pressure washers to clean buckets after servicing. The collected material is taken to the Vermigreen composting facility in Farmington, NY, as well as a variety of local processors in the Rochester region, in an effort to minimize the distance between source of material and where it is processed. As an incentive for signing up for service, subscribers are offered a choice of three reward options distributed in the Spring and Summer months: Finished compost; An edible kitchen plant grown at a local greenhouse; or Donating the compost share to a local garden.

The dashboard on the backend of Community Composting’s website displays all of the applications that facilitate business operations.

Web-Based Innovation

At the heart of Community Composting’s operations is a subscriber interface, billing and routing software developed by Arnold and Kraft that enables the business to operate dynamically and effectively. “We have designed applications within the website to take care of the logistical problems that we face,” explains Arnold. “We custom build every tool so it functions how we want it to.”

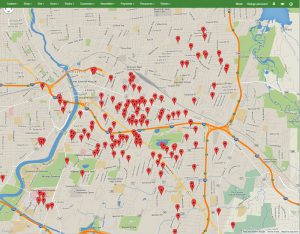

Community Composting’s website includes an “Active Customer Map,” that plots subscribers’ locations on a Google Map. Drivers have the ability to click a location and view individual customer profiles.

Subscriber Interface

When customers sign up, they are entered into the Community Composting system. Subscribers receive a personalized account login to access the customer portal on the website; information entered corresponds to specific sections on the back end. Subscribers are asked for the subscription type they would like (e.g., once a month, biweekly, weekly), as well as further details such as where they plan to put their collection buckets. On the back end, new subscribers appear in the “Needs Assignment” application, notifying operators to add the customer to a route. Additional features for subscribers include the ability to see the collection schedule for the next six months, so they can select dates they are going out of town and do not need service. The website automatically takes them off the route for those weeks, and credits their account the appropriate amount of money back. Subscribers are also informed about how much organic material they divert each week.

Billing

To make billing easy and efficient, Community Composting only accepts credit cards for payment; these are processed exclusively through a secure portal on the website. The website enables Community Composting to track payments via the credit card, and ensure that customer credit cards are valid so operators are aware that a customer has paid for service that week. When a customer has an overdue payment because their credit card doesn’t work, the website system automatically sends them an email. If the customer fails to respond, the system automatically takes them off the collection route for that week. This credit card system also makes refunds “a breeze,” explains Kraft. “By limiting people to the credit card model, it is easier for us and them.”

Routing and Driver Logistics

The website is also designed to make routing and customer monitoring more efficient for drivers. Community Composting has two separate routes for alternating weeks, labeled as “A” and “B.” These routes remain fairly consistent each week. When a new customer signs up or a customer skips a previous week, they appear as a “0” on the routing section of the website, indicating that they need to be assigned a position in the route. Kraft and Arnold will add these subscribers to the route in positions that make the most sense for driver efficiency. For example, Kraft and Arnold will adjust routes based on the way they understand traffic to flow. “We have routes organized so that drivers go to particular areas very early in the morning to avoid traffic,” Arnold says. Whenever Kraft or Arnold adjust a route, it is automatically updated through the website so that drivers have a constantly up-to-date route.

Each driver carries a tablet computer during collection, and each truck is equipped with a wi-fi hotspot. When a driver arrives at a pick up location, they will open up that individual customer’s profile that indicates where the collection container is located. The driver also has a notes section for individual subscribers where they can indicate if a customer has contamination in their container. Kraft and Arnold report that, to date, they have experienced no problem with contamination, but feel this feature will be useful when they increase their commercial customer base, as larger generators can have more problems with contamination in the organics stream.

The driver will also input estimated weight of the pick up (as well as indicate if the customer did not put out a container for pick up). This information is used to generate customer reports that include customer success rate (number of pick ups where container was collected/number of attempted pick ups). “When a customer’s success rate is consistently low, we will call them and say, ‘You aren’t using our service, and it is costing both of us money. Is our service something that you wish to continue?’,” notes Kraft. “This ensures we are not wasting the time or resources with subscribers that do not wish to participate.” He adds that many subscribers cite absent-mindedness as a reason for their lack of participation.

When drivers move on to the next location, they will check off the previous one. Kraft and Arnold have the ability to constantly track the driver along the route, indicated by a pick up location turning from black to green (meaning the driver has been to the location). “This is very useful when it comes to accountability,” explains Arnold. “If a customer calls and complains that we did not service them, we can reference our tracking system.”

The website has a number of other applications that are effective for operating a food scraps collection service. For example, the “Subscribers” and “Active Buckets” sections keep track of current subscribers and buckets in the field. The “Expense Pie Chart” allows them to track the company’s books internally, so they constantly know how much is being spent. “All of these applications are intended to keep our business dynamic, so changes can be updated in real time,” Arnold says. Adds Kraft: “Brent and I are constantly realizing the ability to improve functionality, and make the system better.” They want to find ways to help other food scraps collection services through this software, either by selling it as a package or licensing it to companies. “We are solving issues other services have as well,” they note.