The football stadium, home to the USC Trojans and the LA Rams, went from zero to an average of 83 percent diversion in two seasons. Organics are key to this success.

Marsha W. Johnston

BioCycle June 2017

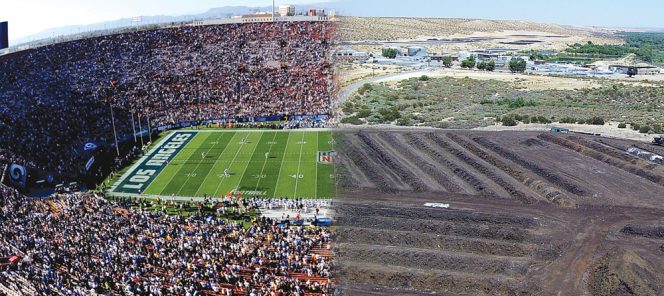

The Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum (Coliseum) opened in June 1923 as the USC Trojans’ home field. In 1932, it hosted the Summer Olympics. And 90 years later, in 2013, the Coliseum’s management got serious about implementing zero waste practices. “When I got here, we weren’t even really recycling,” recalls Brian Grant, USC’s director of operations at the Coliseum since September 2013, the same year USC took over management of the stadium from the Coliseum Commission comprised of city, county and state officials. “We went live with Zero Waste on September 5, 2015, and went from zero percent diversion to zero waste in two football seasons.” On average, in 2016, the stadium had an 83 percent diversion rate.

The feat got the attention of the PAC-12 Conference, which awarded USC First Place in the Fall 2016 Zero Waste Bowl Challenge that it conducts with the Green Sports Alliance. “It is hugely significant for a couple of reasons,” says Jamie Zaninovich, Deputy Commissioner and Chief Operating Officer of the Pac-12 Conference, which is holding the nation’s first summit on greening collegiate athletics just prior to the 2017 Green Sports Alliance Summit this month. “One, because they were able to accomplish it despite the logistical challenges of having an NFL and a high-level collegiate team in the same facility. Second, this is an iconic building. It is not a LEED Gold facility built five years ago. We have had success around the conference with older buildings in Boulder and Cal [University of California, Berkeley], which won the Zero Waste Bowl a couple of years ago. But it takes a little bit more elbow grease in those older facilities to make it work.”

USC’s Sustainability Department had been pushing zero waste at the stadium for a few years, explains Halli Bovia, program manager. While it secured a sponsor partnership with Glad Corp. to pilot a successful Zero Waste Tailgate event in 2011, and piloted several zero waste events at the Coliseum, it took the arrival of Grant to launch an all-out assault. Grant, who had started a recycling and composting program for the University of Minnesota’s 50,000-seat stadium, was the “keystone,” Bovia says. “When he came on board, the university really made it a priority,” adding that USC has set a goal of 75 percent waste diversion by 2020 over its three campuses, various centers, and all Coliseum operations.

USC’s and the Coliseum’s Zero Waste Initiative partners include Athens Services, its waste hauler, and Legends Hospitality, the stadium’s concessionaire, along with BASF, EcoSafe Zero Waste and Waxie. Together, they accelerated stadium greening. “I’m a big proponent of designing with the end goal in mind,’” notes Grant. “It was more efficient to go to the end of the line rather than to take it step by step. It made no sense to do recycling and then incorporate organics at a later date.”

Most service ware at the LA Coliseum has been switched out with compostable products such as cups (top) and cutlery, and paper and fiber-based trays, clamshells and bowls. The Coliseum’s zero waste team opted to go with only compostables and recyclables bins (bottom) in the consumer-generated waste areas. Photos ©Mirza Hasanefendic and by Jason Sanders, EcoSafe

Zero Waste Playbook

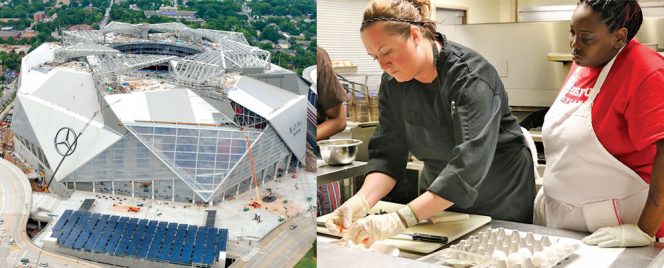

The Coliseum was not built for waste diversion when it was commissioned in 2013, whether it be facilities for zero waste, pre game kitchen prep or post game sorting of compostables and recyclables. For example, says Gian Rafaniello, Legends Hospitality’s general manager for the Coliseum, the few noncompostable or nonrecyclable items it is unable to replace are predominantly prepackaged food products from manufacturers. “A lot of the newer venues have kitchens with more storage, so they can fry their own tortilla chips, for example, and serve them in bulk. Because of our lack of fryers and storage, we have to use a prepackaged product.”

The Coliseum now averages between 10 to 15 percent of such items. “We have about half-a-dozen products that we would like to change out as soon as possible, such as kettle corn bags and some plastics,” explains Grant. “It’s mostly the national brands that are dictated by a national headquarters that we have trouble with, such as Red Vines® and M&Ms®. We’re pushing to minimize the amount of those items we sell.” He expects such national brands will begin reexamining their packaging as more sports venues green their operations. In the meantime, most end up in the compostables stream and get picked out in the waste sorting area.

However, some national brands surprised the team. “We totally thought the Chick-Fil-A® bag was noncompostable, but the company presented us documentation that it is completely compostable,” he adds. “It’s great when you find suppliers like that!”

EcoSafe, which manufactures compostable liners using BASF’s certified compostable biopolymer ecovio, trained concession stand managers, including all of the local vendors in the Coliseum concourse that subcontract to Legends. “We trained them on the program, bin set-up in their stand and what materials go in each bin,” explains Jason Sanders, EcoSafe’s National Manager of Zero Waste Programs. “Then they trained their staff.” Jeff Farrell, USC’s Coliseum Facility Operations Manager, coordinated with the Zero Waste team to give each stand a compostable and recyclable liner, and a one-page document with the program’s guidelines and most recent weekly diversion statistics.

“At the beginning it was tough because we were asking vendors to buy their own products,” adds Sanders. “All of the sub-vendors were purchasing from local restaurant supply stores, which didn’t typically carry compostable products. The biggest challenge was finding compostable cutlery, followed by straws and soft drink lids.”

At this point, most service ware items have been switched out for paper and fiber-based trays, clamshells and bowls, and compostable cutlery and portion cups. Subcontractor noncompliance with the program is “largely on knives, forks and spoons,” notes Rafaniello, adding that the challenge is the additional cost. “We are paying 50 percent more for compostable products than other materials. We’re always trying to find a product that works for us [functionally] and cost-wise.”

At every game, EcoSafe and USC Sustainability audited subvendors on the materials they were using. “If fully compliant, they would get an award next to their menu board showing that they were a zero waste vendor,” says Sanders, noting that subvendors were around 90 percent compliant by the end of last season. This year, the team is discussing a plan to streamline subvendor service ware purchasing by keeping the products on site.

After games, bags of compostables and recyclables are sorted in a designated area of the stadium to remove “true trash.” Photos ©University of Southern California

Postgame Sorting

To facilitate postgame waste sorting, the zero waste team decided early on to go with only two bins in the consumer-generated waste areas: Compostables and Recyclables. “Getting people to make an ecologically friendly choice is hard, so we’ve worked hard to engineer a system where the patron doesn’t really have to make a choice that is friendly to already understood principles [such as recycling],” explains Grant, who adds that people know what goes into recycling bins, making it easier for them to understand that everything else goes in the compostables bin. Items that are “true trash” are sorted and weighed to count against the diversion percentage and hauled by Athens for disposal.

The limitations of the Coliseum’s old infrastructure quickly became apparent after every game when it came time to sort the average of 18 tons of collected material. “Our waste collection point has changed three times in the last three years,” notes Grant. Initially, an area at the adjacent Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena was used for sorting and to store dumpsters. But that venue went under construction to become a new soccer stadium. Then, says EcoSafe’s Sanders, “We had to reinvent and rebuild our sorting location and process.”

The result: A new concrete-floor, cinder block-walled, gated off 1,750-sq.ft. compound next to the Coliseum’s delivery gate that was built in 2016. After every game, a crew of 80 to 100 does a first sweep of the 93,600-seat stadium to pick up compostables that didn’t make it to the bins, and brings them to the sorting area. It then does the same for recyclables. The same crew collects the bags of compostables and recyclables, which also are taken to the sorting area.

Once all contamination is removed, sorters put organics into green 40-cubic yard compactors. Photo by Jason Sanders, EcoSafe

Once all contamination is removed, the recyclable and organic waste streams are loaded into one of four new 40-cubic yard (cy) Marathon “ram”-style compactors. On average, says Grant, about 60 percent of the 18 tons of material from LA Rams games are recyclables — mostly beer cans. Conversely, with no alcohol sold at USC games, 60 percent of the material from Trojan games is organic, mostly food scraps but also fiber and paper-based containers that Athens accepts. Consequently, after USC games, three compactors are used for organics and one for recycling, while the opposite is true for Rams games — three for recyclables and one for organics. Trash is handled in 3-cy dumpsters; recyclables are mixed and compacted together.

Composting Facility

After every game, compacted organics are picked up and trucked 95 miles away to American Organics, Athens Services’ composting operation in Victorville, California. Loads go to a dedicated sorting line where American Organics’ staff conduct a third manual sort, pulling off noncompostable soft plastics, such as film and shipping-related plastics not caught in the waste sorting, according to Sanders.

After every game, organics are taken by Athens Services to American Organics, its composting facility in Victorville (CA). Photo courtesy of American Organics

To date, American Organics has had no trouble with the biodegradability of the compostable products used at the Coliseum, and contamination rates — primarily from conventional plastics not sorted out at the Colisuem — were lower than the 2015 facility average of between 10 and 20 percent, adds Cilloniz. Compost is sold primarily to agricultural growers and donated to civic events.

Program Costs

According to USC’s Grant, the zero waste program could have cost more than $45,000/year, but instead is only about $30,000. Costs have been offset by the Coliseum offering partnership deals to the vendors and Athens. “We developed partnerships with the program to provide financial assistance or cost reductions on products,” he says. “We developed signage with partner logos in areas of the stadium where patrons interact with our zero waste program, so that every time patrons participate in the program they associate our partners with the success of the program.” He adds that the Coliseum also gets $16,000 to $20,000 in commodity credits from Athens based on the volume of recyclables collected during the year.

During the 2017 football season, the Coliseum’s zero waste program will continue to expand and be refined, e.g., by identifying more affordable compostable service ware, sourcing compostable alternatives to nonrecyclable packaging and devising new ways to engage the public on the initiative. “Our intention has always been to develop a working zero waste model at the Coliseum that can be easily replicated at other sports and entertainment venues,” notes EcoSafe’s Sanders. “A commitment that all LA venues for the 2024 Summer Olympic Games would be certified zero waste facilities would be a huge plus in the city’s bid.”

Jeanette Hanna, Biopolymers Market Development Manager for BASF North America, concurs: “The story at the LA Memorial Coliseum is a great example of multiple stakeholders coming together to create a pioneer program that is important for developing infrastructure to effectively manage organic waste on larger scales. Additionally, in some cases, it is the first opportunity for consumers and fans to participate in organics diversion; it’s an important educational tool.”

To that end, concludes Grant, having USC as the program manager is a distinct advantage. “Being a university-managed facility, there are people in place to help with our messaging and carry it forward to a much larger audience,“ he says.

Marsha W. Johnston is a Contributing Editor at BioCycle and an Editor at Earth Steward Associates in Arlington, VA (mwjohnston1@gmail.com).