Oregon Department of Environmental Quality releases findings on psychological, socio-economic and structural drivers that contribute to generation of preventable wasted food in households.

Ashley Zanolli

BioCycle September 2017

While shopping in grocery stores was considered part of most people’s normal routine, many respondents viewed farmers’ markets and gardens as an enjoyable “activity” or “experience.” Photo courtesy of BioHiTech Global Inc.

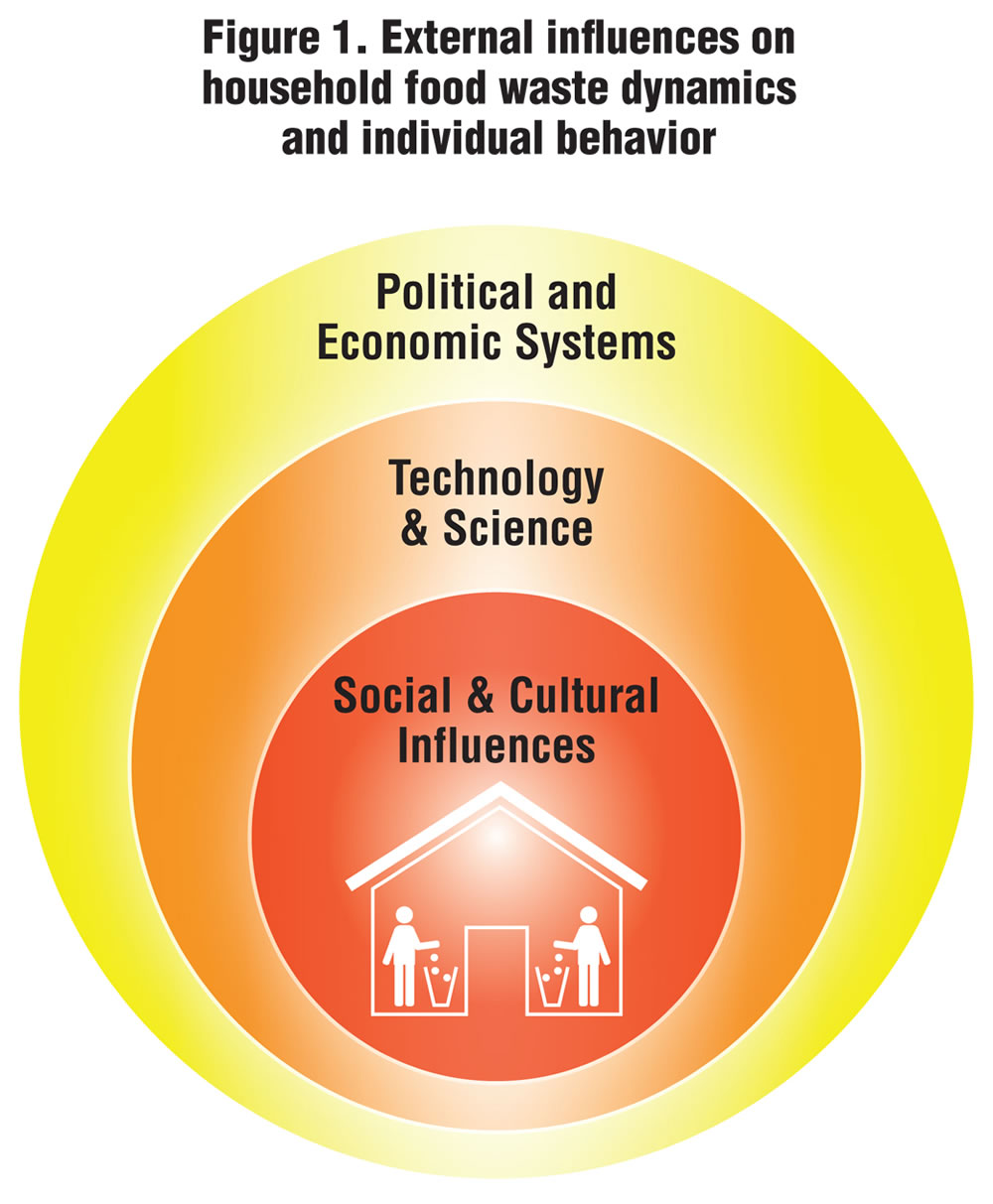

In July, DEQ completed the first part of this research project, a qualitative study to understand the informational, psychological, socio-economic and structural drivers that contribute to the generation of preventable wasted food in households. Figure 1, created by Laura Moreno of the University of California, Berkeley, one of the qualitative study researchers, illustrates how “individual” behavior is influenced externally by household members, social/cultural influences, technology and science, and political and economic factors. It captures the complexity of behavior and the role that the larger food system plays in affecting household food waste dynamics.

The qualitative study consisted of hour-long, open-ended interviews with 32 Oregon residents. Interview questions focused on a range of food-related topics, including shopping, cooking, eating, storage, composting habits, household make-up and dynamics, and knowledge and perspectives on food waste.

Figure 1. External influences on household food waste dynamics and individual behavior

Source: Laura Moreno, UC Berkeley, Energy and Resources Group

Aspirational Relationships

As one survey respondent put it, “I want to like bell peppers, but I don’t like them as much as I should like them, and they don’t get eaten.” Often, good intentions go awry, which was a prevalent theme in the study. Failure to follow through on these intentions often leads to wasted food.

Aspiring for a healthier lifestyle (e.g. eating more bell peppers) was a common theme. To achieve this goal, most people wanted to cook more for themselves at home using healthier ingredients instead of eating out, ordering in, or bringing prepared food home from the grocery store. However, many people noted that the healthy food was not eaten because of time stress or food preferences. As a result, the healthy food is often discarded in place of something that tastes better or works better in a time crunch.

Another common behavior was delaying food disposal in order to alleviate guilt and anxiety related to wasting food. Several respondents reported that they placed excess food in the refrigerator or freezer with the aspirational intention to eat it later. However, the saved food was frequently forgotten or neglected and slowly decayed or developed freezer burn, rendering it inedible. By not discarding the food directly to trash or compost and instead saving it for later, some immediate guilt around wasting food is alleviated.

Study participants also aspired to do better meal planning to reduce waste, save money, or even to improve their “relationship” with food. While many respondents actively engaged in meal planning (or had previously tried and failed), some continued to waste food because they struggled to adhere to their plans. Respondents noted that during stressful events or when time is limited, they are more likely to eat out, order in, or eat premade meals instead of preparing meals at home, even if they have food to eat at home. Other reasons are impulse purchasing and schedule unpredictability.

Location Matters

Buying items while walking down a crowded grocery store aisle versus browsing the inviting displays at a farmers’ market had a different effect on respondents, both in how they felt about the shopping experience and how they valued the food itself. Grocery stores were cited as the most convenient and visited option, however, the experience was listed by some respondents as stressful, sometimes leading to respondents altering purchasing habits to reduce the number of shopping trips they had to make.

While shopping in grocery stores was considered part of most people’s normal routine, many respondents viewed farmers’ markets and gardens as an “activity” or “experience” and associated greater enjoyment when shopping at those locations. Reasons for enjoying shopping at farmers’ markets included feeling a closer connection to nature, having a connection to the grower, and getting food that was perceived as more “natural” and generally tasting better.

Respondents often valued food from the farmers’ market more highly than food from the grocery. This preference, however, could result in different wasting behaviors. For example, one respondent noted that they would savor the food and therefore ration it, which sometimes resulted in the saved portion spoiling and being discarded. Some respondents noted that foods purchased on an impulse at farmers’ markets were often forgotten because they weren’t considered as part of the meal plan for the week.

Size Matters

Quantities available to purchase as a result of how foods are packaged or sold was a major theme throughout the study. Single person and small households indicated that provisioning or preparing the correct portions of food could be difficult, especially when they don’t enjoy eating the same meal for several days. Delivery minimums also generated uneaten food. As one respondent said, they don’t over order food on purpose, but when there is a minimum for delivery, “You gotta order a pizza and a side.”

For people cooking at home, portion sizes available at grocery stores, quantities provided in recipes, and the size of cookware were all mentioned as barriers to preparing a smaller amount of food (e.g. how do you make a casserole for one person in a normal casserole dish?) One respondent mentioned that when they buy pasta sauce, they aren’t able to use the can in one sitting and by the time they are ready for more pasta, the sauce has already gone bad. This preference for variation in their diet was a common contributor leading to wasted food, and items often ended up “lost in the refrigerator,” or as one person described it, the place where “food goes to die.”

Several respondents placed excess food in the refrigerator or freezer with the aspirational intention to eat it later. However, saved food was frequently forgotten, eventually rendering it inedible.

Commonly Discarded Items

When asked to self-report which food items were most commonly discarded, the responses echoed previous findings, such as those around “healthy food” spoiling and leftovers going bad. Buying in bulk also created challenges. In households with young children, portions of kids’ meals were commonly wasted, and parents noted that both the preferences and appetites of their children often varied widely, making it difficult to predict how much and what to buy. One parent said that cherry yogurt was often tossed in their household since it’s the one flavor in a variety pack their children won’t touch.

Other commonly discarded items included partially-consumed beverages left out too long, such as a cup of coffee that’s gone cold or soda that’s lost its carbonation. “Food fads” were another cause of waste, which happens when a food item suddenly surges in household popularity, is over-purchased and then quickly forgotten when the individual tires of it.

“Hidden” Waste

Among respondents who are either currently diverting discarded food to composting or who have in the past, there was a common preference for composting over throwing food in the trash. A sentiment frequently shared was “you either use it, compost it, or it goes to the dogs. So nothing ever really gets wasted.” Another person added, “Sometimes you can’t eat the [salad] greens fast enough and they get slimy. But those just go in the compost, so it’s not really considered waste.”

Composting has been successfully promoted as a more environmentally appropriate alternative to landfilling wasted food, and this is reflected by the general support and excitement that people expressed about composting. While composting is diverting discarded food from landfills, could it also contribute to increased waste by alleviating some of the guilt associated with discarding food? In interviews, people indicated that they felt much better about discarding food to composting, while others justified over purchasing with the fact that they could compost the excess food if it didn’t get used.

Moreover, composting was also commonly described as separate from the trash, so the amount wasted may be effectively “hidden” from view. This may prevent people from accurately characterizing their discarded food and thus limit their ability to identify methods to reduce wasting in the first place, something that points to the need to effectively combine prevention and composting messages so that they work together, and not at cross purposes.

Oddly Shaped Fruit And Other Findings

The interviews produced additional findings that DEQ will investigate in subsequent research. For example, many respondents commented on the aesthetics of food, such as being more forgiving of oddly shaped or blemished produce if they knew it was grown organically. Additionally, some people mentioned that when they purchase conventional produce, they took more time to scrub and peel those items. The food safety messaging about peeling some produce may contradict suggestions for food waste prevention that promote eating the peels.

Another theme was seasonality as a factor in wasted food. While the types of food that are eaten and discarded during certain times of year (e.g. watermelon during the summer) are well known, some respondents shared that they were less likely to compost when it’s cold or rainy. As a result, there may be a seasonality in whether food waste is diverted from disposal, with a lower diversion rate in cold and rainy months. These themes, as well as themes related to the impacts of date labels on food purchasing and busy, unpredictable schedules, are explored in greater detail in the report.

What’s Ahead

The act of discarding food is simply the last step in a series of behaviors that may be spatially and temporally disconnected from the actual “disposal” to composting, garbage, animals, or other destinations. As a result, understanding the “reason” why food is discarded can be difficult and involve a large variety of factors.

The findings from this study illuminate key themes that are applicable to the larger topic of wasted food and related household behaviors. These findings have helped shape subsequent DEQ research, which is currently ongoing and will be shared in future issues of BioCycle.

Ashley Zanolli is Senior Policy and Program Advisor at Oregon DEQ. This study was conducted by Portland State University’s Community Environmental Services and the University of California, Berkeley, under the guidance of DEQ staff. The full report, including methodology, is available on the Oregon Department of Environmental website (link at BioCycle.net). For more information, contact Zanolli.Ashley@deq.state.or.us.