State and local governments have explored policy avenues to reduce and manage food waste.

E. Broad Leib, K. Sandson, L. Macaluso and C. Mansell

BioCycle September 2018

The issue of food waste has significant impacts on the environment, the economy, and on food insecurity. As awareness of this problem has grown, federal, state, and local governments have explored policy avenues to reduce and manage food waste. Organic waste bans are one category of policy that has emerged in recent years at the state and local level to address food waste. Defined broadly, organic waste bans refer to policies that restrict the amount of food waste or organics that certain entities can dispose, as well as those that require diversion or subscription to an organics processing service.

By placing restrictions on the disposal of organic waste, bans can drive food waste generators to explore more sustainable practices, such as source reduction, donation, composting, and anaerobic digestion (AD). The Harvard Law School Food Law and Policy Clinic (FLPC), with support from the Center for EcoTechnology (CET), conducted an analysis of existing and proposed organic waste bans, studying the policies themselves as well as the experiences of states and localities in implementing and enforcing these policies.

The toolkit consists of six sections that cover the following topics: Existing legal landscape; costs and benefits of waste bans; decisions and considerations for designing organic waste ban policies; barriers and challenges to implementation and enforcement; other policies and programs that can impact how waste bans function in practice; and technical assistance and public education. This article provides a brief summary of the contents of each of these sections.

The Legal Landscape

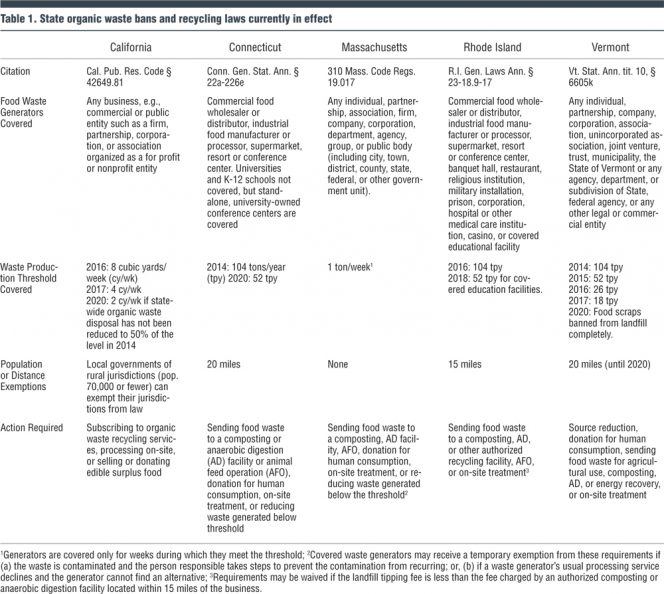

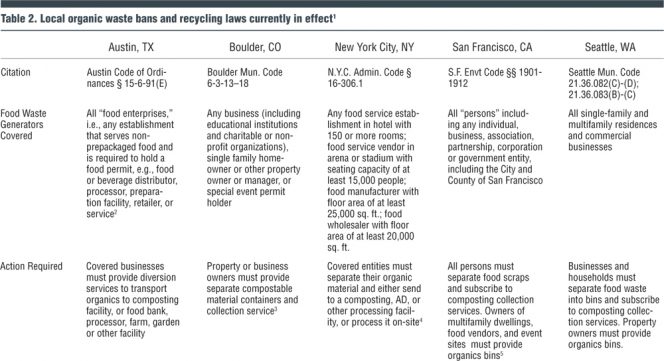

Five states and six municipalities have implemented organic waste bans or mandatory recycling laws. Most of these policies took effect within the last five years. The states are California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Vermont; the municipalities are Austin (TX), Boulder (CO), New York City (NY), San Francisco (CA), and Seattle (WA). Additionally, Oregon Metro, the regional government for the Portland area, passed a policy in July 2018 that will require some businesses to divert food scraps. The Legal Landscape section in the toolkit summarizes each of these policies, as well as a proposed organic waste ban in New York state, specifically outlining when the policy took effect, what kinds of entities are regulated, what actions those entities must take in order to comply, and how these policies can be enforced. For an overview and comparison of the different policies, see Table 1 (state) and Table 2 (local).

Costs And Benefits

The decision to implement an organic waste ban or other diversion policy necessarily involves balancing potential economic, environmental, and social costs and benefits. Two states, Massachusetts and New York, have conducted analyses of their proposed or implemented organics bans. The Cost and Benefits section examines these analyses and includes examples from other states and localities in order to identify some of the potential sources of revenue and costs associated with implementation of a state or local organics ban.

These analyses reveal several benefits of implementing a ban beyond a reduction of food waste disposal, including creation of job opportunities, reduction in hauling and tipping costs, and reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. These benefits must be balanced against implementation costs, including the costs of building new infrastructure, one-time collection equipment investment and staff training, ongoing equipment maintenance, hauling food waste from generators to processing facilities, and tipping at those facilities.

Ultimately, states and localities may see significant net economic benefits, as well as environmental benefits, from implementing organic waste bans. Some stakeholders such as food recovery organizations and organics processors and haulers may also benefit from opportunities for growth. Others, such as businesses and institutions that generate food waste, may experience initial concerns and costs associated with compliance, but may be able to offset these costs and even experience economic benefits through reductions in purchasing costs, tax incentives for food donation, and decreased disposal costs.

Designing Policy

Policies that aim to reduce the amount of food waste sent to the landfill are not one-size-fits-all. Each state or municipality that develops such a policy or set of policies must make decisions based on its geographic, economic, political, and cultural characteristics; desired outcomes; and resource constraints. This section of the toolkit outlines some of the decisions a state or municipality may face in designing an appropriate policy to reduce and manage food waste:

• To Ban or Not to Ban: A state or locality must first decide whether to pursue an organic waste ban or mandatory organics recycling law, or whether to pursue alternative solutions such as a zero waste plan or a collection of ancillary laws and programs. Factors to consider in making this decision may include the political feasibility of passing a ban, the availability of resources such as funding and staffing, and the availability of existing infrastructure for processing organics.

• Organic Waste Ban or Mandatory Recycling Law: If a state or locality chooses to pursue an enforceable organics policy, it will need to determine whether to structure its legislation or regulatory requirements as an organic waste ban or as a mandatory organics recycling law. Both are generally enforceable policies enacted through legislation or regulation, but an organic waste ban prohibits covered entities from disposing of organic waste or food waste, while a mandatory organics recycling law requires covered entities to take specific actions to recycle their organic waste, such as subscribing to a collection service.

• Types of Generators to Cover: Policymakers will need to determine what categories of food waste generators to regulate. Most organic waste bans cover only large commercial food waste generators, while some also cover institutional generators such as educational facilities, prisons, and hospitals. Some states and localities also impose requirements on residents.

• Distance Exemptions: Another decision that states and localities will need to make is whether to exempt food waste generators from a ban if they are not located within a certain distance of a facility that can process organics, such as a composting or AD facility. Several states have included distance exemptions in their organic waste bans. Including a distance exemption can make waste bans more feasible to both pass and to implement, but it can also limit the efficacy of waste bans by leaving large generators outside the coverage of the law, and may make these policies less effective at driving development of processing infrastructure across the state.

• Waste Production Threshold: States and localities may also choose to limit which food waste generators are subject to an organic waste ban based on how much waste a generator produces. States and localities have determined their coverage threshold in a number of different ways, including weight or volume of waste generated, or square footage of the food establishment. Some states also lower the waste generation threshold over time, which can reduce regulatory burdens on generators and increase political buy-in at the start, and later cover additional generators as processing infrastructure develops.

Barriers And Challenges

States and municipalities are likely to face challenges in the process of developing, passing, implementing, and enforcing diversion policies. This section of the toolkit addresses some common challenges including:

• Political Considerations: Like most policies, waste bans can raise political concerns and generate significant pushback. Several states and localities have reported that political compromises were necessary to pass their laws, or have found that political challenges halted plans to pass, implement, or expand such bans. Supporting proposed policies with economic studies and engaging a wide range of stakeholders, including food businesses, food rescue organizations, haulers and processers, can increase political support for these policies.

• Funding: Many states and localities with waste bans or zero waste plans struggle with a lack of resources and dedicated funding for operations and enforcement. Insufficient funding can hinder the efficacy of waste bans by limiting the capacity of states and localities to implement, enforce, and conduct outreach around these laws.

• Infrastructure: Many states struggle with a lack of sufficient infrastructure, including composting and AD facilities, collection equipment, and food rescue infrastructure, to support an organic waste ban. Several states have experienced significant growth in processing infrastructure since passing an organics ban, due in part to an increased willingness to invest in processing facilities once a policy exists that drives demand for these services. However, many states continue to have insufficient processing capacity to handle all of the food waste that must be diverted under their organics bans.

• Enforcement: The costs and logistics of enforcement pose another challenge to states and localities implementing organic waste bans. While some localities have sought to monitor individual generators, e.g., monitoring bins for source separation at pick up, other states have used alternative enforcement strategies, such as carrying out inspections on the tipping floors at waste transfer stations or at landfills, or intervening primarily when they receive a report of possible noncompliance.

Other common challenges states and localities face in implementing and enforcing organic waste bans include the impacts of regional market dynamics, as well as food scrap contamination.

Beyond The Ban

In addition to organic waste bans or mandatory recycling laws, there are many other related policies that can support these laws and play an important role in determining the efficacy of an organics ban. For states and localities that are unable or choose not to implement a waste ban, implementation of these policies can also help reduce food waste and facilitate increased diversion even in the absence of a full-scale ban. This section outlines several key policy options, including:

• Permitting for Composting and AD Facilities: Permitting requirements and procedures that encourage development of composting or AD facilities without imposing unreasonable costs or delays are important to support development of organics processing infrastructure. In particular, tiered permitting structures and streamlined application processes can facilitate development of composting and AD facilities. Several states, including New York and Rhode Island, have revised their permitting regulations in recent years to reduce barriers to obtaining permits.

• Pay-As-You-Throw (PAYT) Pricing Structures: Some municipalities use a PAYT model, otherwise known as unit-based or variable-rate pricing, to charge residents for collection services based on the amount of waste that they throw away. By charging residents more when they dispose of larger amounts of waste, or by altering the cost of trash disposal relative to recycling or composting, PAYT models can incentivize residents to decrease their trash generation and increase their recycling or other forms of waste diversion.

Other policies and programs discussed in this section include: grants for food waste reduction, recovery, and recycling; food rescue networks and infrastructure; hauling arrangements and contracts; zoning for composting and AD facilities; renewable portfolio standards to support biogas from AD facilities; tipping fees; and flow control.

Technical Assistance And Public Awareness

Technical assistance (TA), outreach, and public education play an important role in facilitating compliance with an organic waste ban and increasing buy-in from businesses and residents. This section of the toolkit outlines several methods and strategies for providing TA and public education.

• Technical Assistance: Technical assistance typically involves one-on-one assistance designed for generators, food rescue organizations, haulers, processors, associations, or government officials to support compliance with waste reduction laws. States and localities may choose to promote the use of TA regardless of whether or not lawmakers intend to institute a ban because these services have the potential to increase diversion even in the absence of any regulatory requirement. The availability of TA plays an important role in supporting organic waste bans and other diversion policies by increasing awareness of these policies and helping generators, haulers, and processors prevent mistakes and realize benefits as they seek to comply.

• Public Outreach and Education: Outreach and education are important to raise awareness of food waste reduction strategies, and increase buy-in and compliance with a waste ban, both among food waste generators and the general public. Awareness and buy-in from the general public can make the process of implementing an organic waste ban or related program smoother, particularly where organics bans or organic recycling mandates cover residential generators. Education and outreach directed at food businesses is also important to achieving state and local food waste reduction goals and compliance with organics bans, especially when paired with TA. Ongoing education and training can help sustain implemented diversion programs, support continued compliance, and lead to new opportunities for diversion.

Emily Broad Leib, Director, and Katie Sandson, Clinical Fellow, are with the Harvard Law School Food Law and Policy Clinic. Lorenzo Macaluso is Director of Client Services and Coryanne Mansell is a Program Specialist at the Center for EcoTechnology. The toolkit will be available on the Harvard Law School Food Law and Policy Clinic website.