Gregg Hayward

Scrubbing system (above) removes hydrogen sulfide, moisture and then siloxanes from the biogas prior to being used by the cogeneration engines. Pump trucks offload fats, oils and grease (FOG) into large storage containers (left). FOG is slowly injected into the digesters. Photos by Doug Pinkerton

In 2007, the City of Gresham, Oregon’s Mayor, Shane Bemis, signed the US Council of Mayors’ Climate Action Agreement. Growing out of that declaration, the City began envisioning new ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and increase operational efficiency to save money. Upgrading all street lights to LED, which has saved Gresham $700,000/year, and upgrading the 20 million gallon/day Wastewater Treatment Plant (WWTP) to energy net zero are some of the big wins.

“We’ve had a lot of fun figuring out how to put this project together,” explains Alan Johnston, Senior Engineer and driving force behind the journey to net zero. “When I first started working for the City in 1991, I was absorbed in figuring out how to run the facility. But as I came to better understand the system, and learned about new technology, I became interested in trying to find ways to make the plant more efficient, while still doing its job. These facilities consume massive amounts of electricity (the WWTP is one of the largest energy users in the city), and I wanted to find ways to change this.”

Anaerobic digesters were installed at the plant around 1990. Biogas was fed, without any treatment, to a 250 kW generator. “It was old technology, and only helped power about one-quarter of the plant,” notes Johnston. “We wound up turning it off in 2002 when it burned out.” In 2005, the City installed a 400 kW combined heat and power (CHP) cogeneration engine with a modern biogas scrubbing system.

The Net Zero journey began in 2009 when the WWTP received a grant from the Oregon Economic Development Commission to study ways to increase the environmental and operational efficiency of the treatment plant. An outcome was a study on the benefits of accepting fats, oils and grease (FOG) to remove them from the waste stream and instead use them to generate electricity. The study delved into the potential return on investment (ROI) of the project. The conclusion was that it would be cost-effective with an ROI of 7 years based on revenues generated by a FOG tipping fee at the facility and avoided electrical utility fees.

“This document was what we passed around to get interest from City management and elected officials,” says Johnston. “They came on board with it, and it became part of the capital improvement plan for the treatment plant.” Investment began in the 2010 capital improvement cycle where net zero became a real goal. The aim was to make improvements cost-effective and bring the plant into net zero energy use range. A formal Energy Management Team was created, and it established a goal of achieving Energy Net Zero at the WWTP within 5 years (by 2015). The Energy Management Team met monthly to assign appropriate tasks to staff and ensure the energy net zero goal was met. In February 2015, on schedule and on budget, the very first energy net zero month occurred. The WWTP generated more electrical energy on site from renewable biogas cogeneration and solar power than the plant consumed. The facility is now in its fourth year of operation as a net zero WWTP.

Several consultants were hired to help do studies to prove the feasibility of the plant’s net zero goal, along with design work and construction. Johnston oversaw the project, and currently oversees the management of the WWTP program. Once the energy net zero path forward was figured out in 2010 with support from management and staff, five major capital upgrades were phased in over a five-year span.

- Phase 1 (2010): Installation of a 420-kW solar system

- Phase 2 (2011): Power conservation project that reduced plant-wide power consumption by 17 percent

- Phase 3 2012): Installation of a 10,000-gallon FOG receiving station

- Phase 4 (2014): Expansion of the FOG receiving station to 30,000 gallons

- Phase 5 (2015): Expansion of the cogeneration system from 400 kW to 800 kW (two, 400 kW cogeneration engines)

One of two 400 kW Caterpillar engines. Photo by Doug Pinkerton

Integrating With Utility

Passing through the gate at the WWTP today, one is met by a large array of solar panels, a very visible note that energy production is happening. While phasing in the solar array, Johnston worked hand in hand with Portland General Electric (PGE), the area utility provider. They, along with the Energy Trust of Oregon and the Oregon Department of Energy, helped fund about 40 percent of the overall cost of the energy-related capital projects.

The Energy Trust of Oregon’s model is a vital piece of the puzzle; energy users across the state, both residential and commercial, pay a small additional fee on each utility bill. That fee is added to a fund that supports the Energy Trust, which uses the money to provide monetary incentives for commercial, residential and city projects that increase energy efficiency or produce sustainable power. These include free energy conservation toolkits for homeowners, and rebates for a wide array of commercial and industrial energy efficiency upgrades.

Johnston collaborated with PGE and the Energy Trust to work out the details of incorporating an electricity-generating system into the WWTP’s grid. The plant generates the energy it needs most of the time, more than it needs some of the time, and sometimes relies on power for the grid. On average, the WWTP generates about 10 percent more electricity than it needs. Because the electricity is produced with renewable biogas, it has environmental attributes that can be used to lower the carbon footprint of the City.

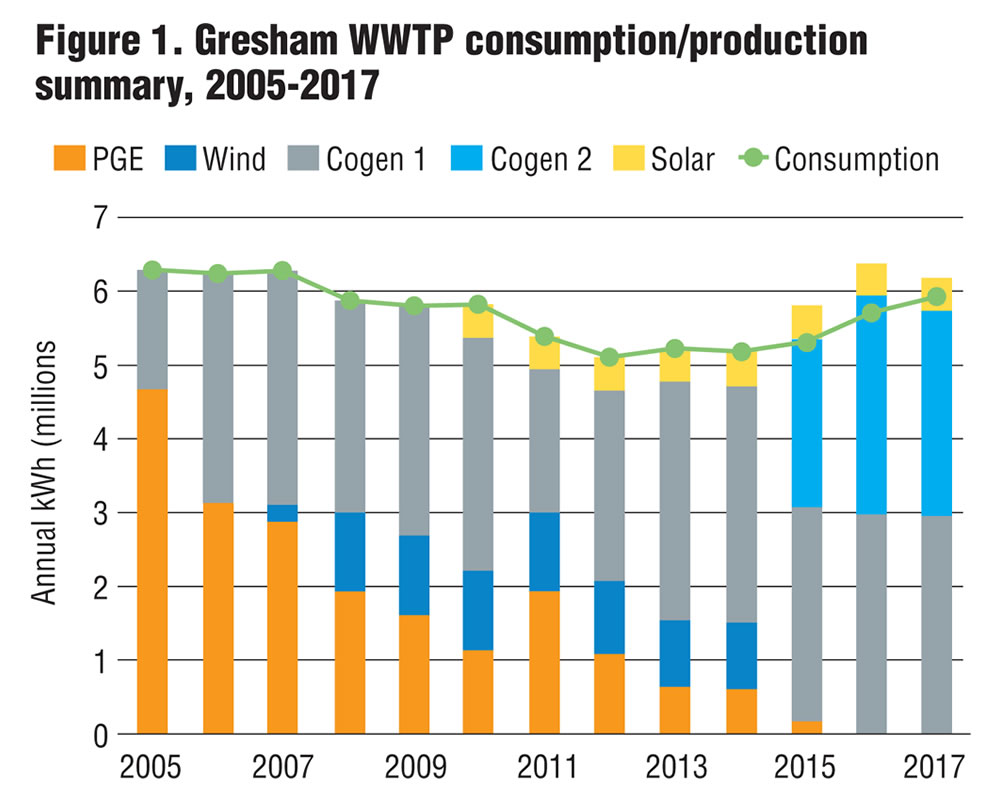

Figure 1. Gresham WWTP consumption/production

summary, 2005-2017

Grease Benefits, Project Payback

Every day, several pump trucks drive around Gresham and the Portland metro area collecting FOG from restaurants and commercial kitchens. The pump trucks offload at the WWTP into large FOG storage containers. The FOG is slowly injected into the plant’s anaerobic digesters. “FOG has a lot of energy stored in it, about 12 cubic feet of biogas produced for every gallon injected into the digesters,” explains Johnston.

The biogas is then pumped through pipes into two massive yellow 400 kW Caterpillar engines. The two cogenerators produce the 6 million kWh/year needed to operate the entire WWTP. This energy runs multiple processes throughout the WWTP that aerate, mix and treat wastewater, eventually discharging the clean water to the nearby Columbia River.

The numbers really do tell the story, he adds. “We had a $50,000/month energy bill from PGE. Now we have a $4,000 monthly bill but are also generating $350,000/year in revenue from FOG tipping fees, hence the relatively quick 7-year payback.” The numbers are also equally impressive in terms of greenhouse gas reductions. Being in the hydropower-rich Pacific Northwest, it’s possible to achieve a light greenhouse gas (GHG) power mix, but looking at it on a national average, this project reduces overall carbon impact significantly. Purchased power has seen a reduction of 3,100,800 kWh since 2007, equivalent to 2,308 MT CO2e of GHG emissions (Figure 1).

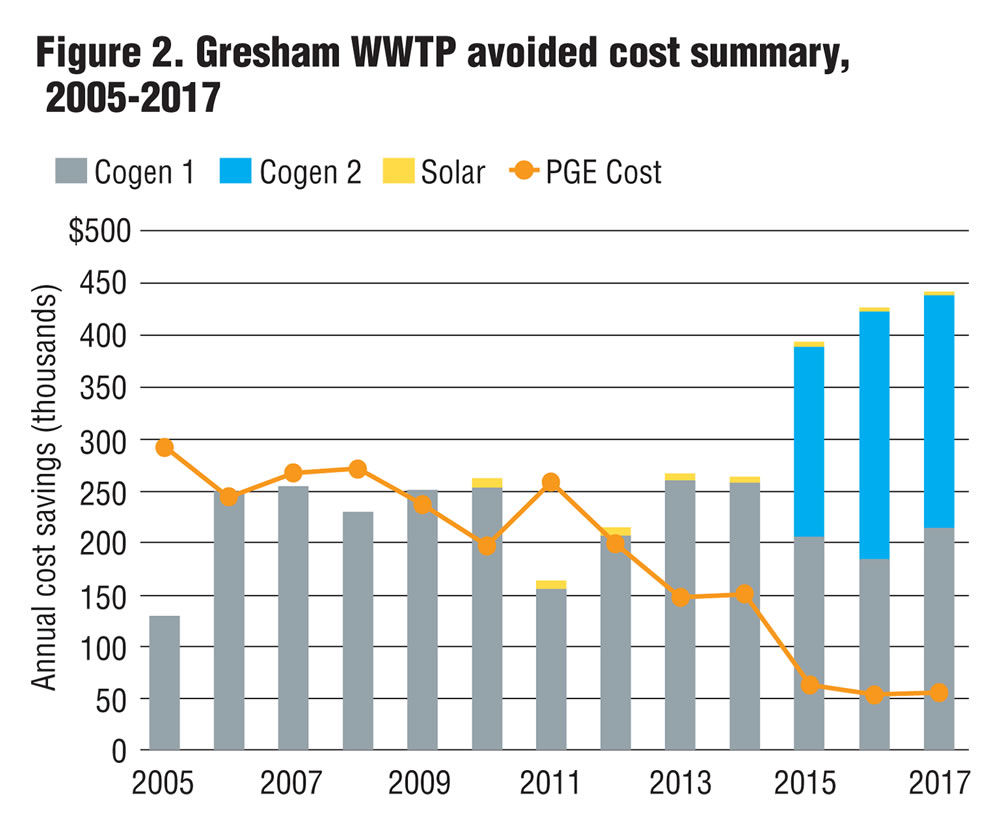

Figure 2. Gresham WWTP avoided cost summary, 2005-2017

Figure 2 shows the avoided costs resulting from the switch to 100 percent renewable energy. The City of Gresham has saved about $4.9 million and avoided $2.1 million in utility costs since 2006. The $4.9 million includes FOG revenues. The two cogeneration engines and the solar array account for $3.4 million in avoided costs. “We look at the WWTP story as a huge win for the city, and an inspiring model of how other businesses can think in the short and long term about how they can become both more financially and environmentally sustainable,” says Shannon Martin, Recycling and Solid Waste Manager.

Replicability

Concepts that have been learned and applied in Gresham can be used elsewhere, especially at medium to large wastewater treatment plants, notes Johnston, “The main function of what is done in our Energy Net Zero Wastewater Treatment Plant can be done in many municipalities around the country. Adding FOG to a municipal WWTP makes sense if you have some extra capacity in your existing anaerobic digesters or are looking at expanding your digesters. Being in a central, easy to reach location for haulers helps. These are all things to consider.”

He adds that one of the first steps is to study your area, and demonstrate the ROI. “Figure out what your tip rate would be to make the system pencil out and see if that rate makes sense in your local market,” he says. Gresham staff looked at and projected future electric utility rates and FOG tipping fees and were able to create a financial model. Management and staff were a bit skeptical of the cost-effectiveness of almost $10 million in projects over five years. However, the detailed accounting of the payback, costs, grant opportunities, avoided utility costs and FOG tipping fee revenues prepared by the staff led to approval of the capital projects. “We estimated at the beginning that almost 40 percent of our capital projects could be paid for with grants from the Energy Trust of Oregon and the Oregon

Department of Energy,” he adds. “In the end, we got 38 percent or $3.5 million in grants for the projects.”

Johnston emphasizes the critical role of energy efficiency. “Always, first and foremost, save energy. It’s the biggest bang for your buck. Before we started the FOG receiving and cogeneration projects, we did three efficiency projects — low energy turbo blowers, fine bubble diffusers in aeration basins, and linear motion mixers in digesters — that dropped the plant’s overall energy usage by 17 percent.”

Finally, he notes, work with your local and state partners to modernize the regulations to allow for innovation and efficiency. “Some states still don’t allow export of power within the grid. Some years ago, Oregon changed the net meter rules that allowed us to export to the grid.”

Gregg Hayward is the City of Gresham’s Business Sustainability Coordinator. Alan Johnston can be contacted at Alan.Johnston@GreshamOregon.gov.