Laura Moreno

In a Donald Duck cartoon from the 1950s, Donald has an apple orchard. As he is harvesting the apples, he notices that bites have been taken out of them. He soon discovers that mischievous Chip and Dale have been eating his apples, leaving only the cores behind. Donald battles with Chip and Dale, but not before seemingly hundreds of apples are eaten leaving only the core.

Rewatching this after years of working on food waste and thinking a lot about the concept of edibility leaves me asking the question …”were Chip and Dale wasting perfectly edible food when they discarded those apple cores?” Apple cores might not be commonly eaten (though, I would bet that more people you know eat them than you think). But what about other parts of foods considered edible by some people and not others? Who decides what is edible and what is not? What about broccoli and cauliflower stalks? Chicken skin and bacon grease? Peels of potatoes or carrots? Watermelon rinds? Pumpkin seeds? Tomato cores?

Most people agree that edibility is a complex concept to address in the quantification of food waste, but some express doubt about its overall importance. Why would we care about whether potato peels and broccoli stalks are considered “edible” or “associated inedible parts”?

Here are the top three reasons why it does matter…

1. Some definitions, and thus some estimates, of food loss and waste (FLW) only include the edible portion of food (e.g. USDA and FAO). These definitions mean that the inedible portions of food are outside of the boundaries of what is considered food waste.

2. New legislation is starting to include concepts or set specific goals related to edibility and/or recoverability. For example, California’s SB 1383 requires jurisdictions to meet a goal of 20% edible food recovery. The United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goal 12.3.1 seems to be targeting the edible portion of FLW, though how it will be implemented is not yet clear.

3. Food waste prevention strategies generally focus on the edible or “avoidable” portion of FLW. An example is the Natural Resources Defense Council’s (NRDC) SaveTheFood.com website, though there is also guidance to help people eat more parts of items, such as peels or broccoli stalks, which some people currently consider inedible.

Why Bother To Measure Edibility?

While we argue that edibility conceptually matters, how much does it matter in practice? Is it just a small percentage of food items that are not clearly considered edible or inedible within a culture?

In a survey of consumers in the United Kingdom, Nicholes et al (2019), found views of edibility vary considerably even within national boundaries. Edibility is not an inherent feature of a food item, but is largely influenced by social, cultural and technological factors. A 2017 report by the UK’s Waste and Resources Action Programme (WRAP) noted that almost any food item can be made ingestible or digestible with enough technology or treatment. Additionally, people acknowledge knowing that food items are edible, but don’t eat them due to preference or routine.

The widely varying views of edibility make creating a universal classification difficult. To account for this, WRAP categorized food waste into three categories, one of which was potentially avoidable. The NRDC also categorized food waste into three categories, one representing “questionably edible” food parts, such as broccoli stalks. WRAP found that 18% of total household food waste was potentially avoidable (Gillick & Quested, 2017) while NRDC found that 11% was questionably edible (NRDC, 2017). These findings suggest that a relatively large proportion of discarded food items could be considered either edible or inedible, depending on how food parts are classified. So, why does it matter that a fairly large proportion of items fall into a category of debatable edibility?

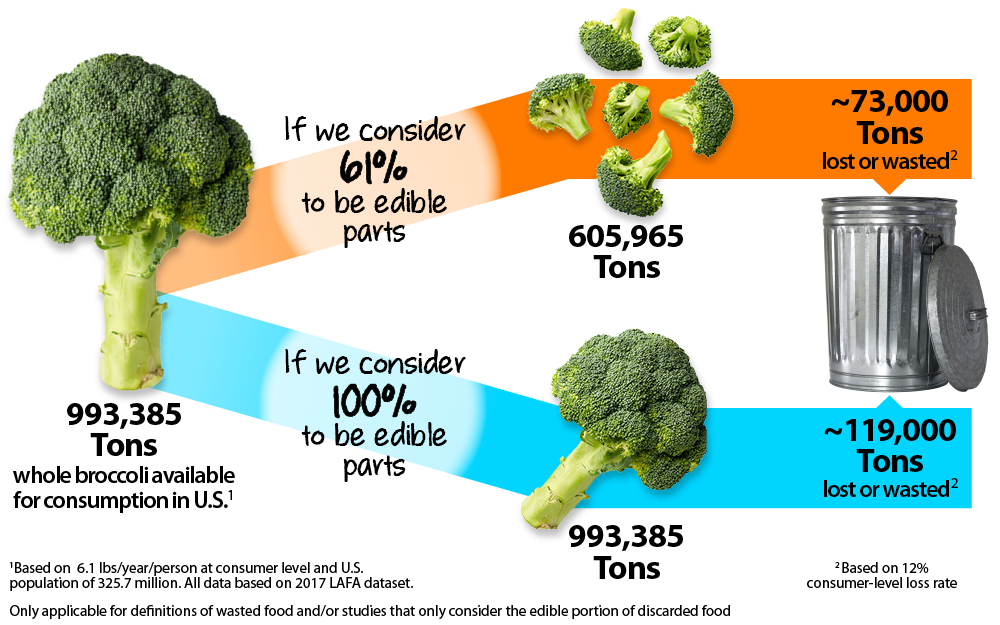

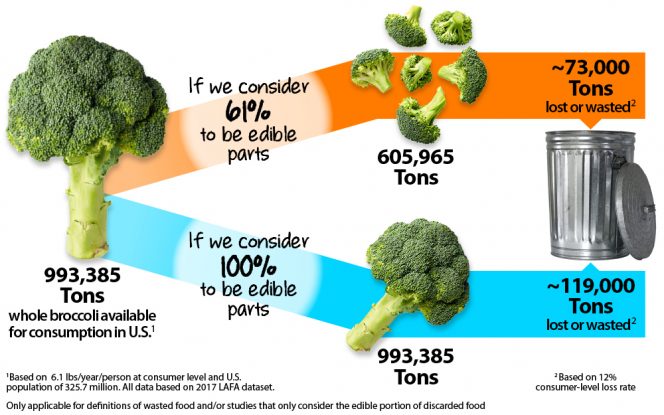

Using the great information from USDA’s Loss-Adjusted Food Availability (LAFA) dataset, let’s use broccoli as an example to illustrate the potential impact of how we classify edible and inedible parts of food. According to LAFA, it was estimated in 2017 that approximately 6.1 lbs of fresh broccoli per person were available at the consumer level in the United States. The consumer level loss and waste rate for fresh broccoli estimates that 12% of that available broccoli was not eaten, but was lost or wasted at the consumer level. If the broccoli stalk is considered edible (so 100% of the broccoli you buy at the store is edible), it would be estimated 119,000 tons of edible fresh broccoli was discarded in 2017 in the United States, assuming a population of 325.7 million.

If the broccoli stalk is considered inedible (meaning that only 61% of broccoli you buy at the store is considered edible as is estimated by the USDA), it is estimated that only 73,000 tons of edible fresh broccoli was lost or wasted in the United States in 2017. At the national level, that is a difference in estimates of 46,000 tons.

If edible and inedible parts are both considered together, what proportion of food is considered edible makes no difference. However if, as mentioned previously, a definition or study of food loss and waste (FLW) only considers the edible portion, then the estimate of wasted food could be significantly different based on the classification of food parts as edible or inedible. As illustrated with the broccoli example, considering the stalk to be inedible would result in an estimate of FLW for fresh broccoli that is 46,000 tons lower than if the stalk was considered edible.

Edibility And Wasted Food Estimates

In the absence of a standard definition, it is important to consider how edibility might influence our estimates of wasted food, including how we track progress over time and what we identify as hot spots for intervention. For example, efforts to reduce discards from broccoli stalks (e.g. retailers using stalks in slaw or soups) would not result in reduced amounts of estimated food waste if inedible parts are excluded from the definition of food waste.

A transparent and clear description of how edibility is categorized is necessary to ensure comparison between definitions and studies. Given the potential magnitude of difference, it is important that the categorization of edibility be consistent (Moreno et al., 2020). Otherwise it will not be clear if differences in estimates (e.g. tracking changes over time) are a result of actual differences or an artifact of quantification. Taking it one step further, Nicholes et al (2019) suggests creating a standard definition of edibility for a region or nation using a survey to gauge both what food parts people consider inedible and which parts they also tend not to eat.

Aside from quantification and measurement, the varying conceptions of edibility may play an important role in future initiatives and programs targeting items that can be considered either edible or inedible. For example, many people peel food items because of potential exposure to pesticide residue (e.g. Dirty Dozen) so encouraging people not to peel food items may result in conflicting messaging with public health and food safety issues. On the other hand, pushing the boundaries of edibility may also be a method to engage people who express creativity through cooking and enjoy experimentation (e.g. recipes to help people creatively and deliciously use all parts of food items).

Finally, manufacturers and retailers will continue to play an important role in maximizing the use of food parts potentially considered inedible, while encouraging people to buy the parts of food they actually eat. For example, people who don’t like broccoli stalks can be encouraged to purchase “only the florets” thus allowing the stalks to be used in other applications, such as slaws or soups.

To answer my own question about whether Chip and Dale were discarding perfectly edible apple cores…the answer is “it depends on who is counting.” However, the key takeaway isn’t to prescribe what is edible and what is not, but that researchers and practitioners consider the question of edibility in their quantification and measurement. This is not a recommendation to get people to change their views of edibility to waste less food, but to recognize that the issue of food waste is both an issue of “waste” and “food” — and how people perceive food, including its edibility, shape behaviors.

Laura Moreno is a recent graduate from the Energy and Resources Group at the University of California at Berkeley. For her PhD, she conducted mixed methods research on household-level food waste with a focus on measurement and consumer behavior.