Sally Brown

The virus that causes COVID-19 is SARS-CoV-2. In Part I, I discussed that much of what we know about COVID-19 centers around the behavior of viruses from the same family as SARS-CoV-2, and increasingly some of it from the virus itself. The last section of Part I explained how this virus is wrapped up in an envelope and that outside of your body, enveloped viruses, almost certainly including SARS-CoV-2, are frail and delicate things.

That knowledge informs the focus of Part II — putting SARS-CoV-2 in the context of municipal wastewater treatment and composting. The first thing to consider is whether there is a real possibility that any of the virus, let alone a gang of these hijackers, could make it into the wastewater plant or the compost feedstocks. We know that there is some fecal shedding of SARS-CoV-2, so the answer there is within the realm of possibility on the wastewater.

Following The Flush

Let’s follow the feces through the system to start — follow the flush so to speak. There have been many studies on presence and persistence of different coronaviruses in feces and a few on SARS-CoV-2 that focus on whether the different viruses are present. The tools used to detect a particular virus in an environmental sample typically test for presence and not for viability. In other words, they are sufficient so that you can spot enough of the package or contents to know that it is present, but not sufficient to see if it can cause harm. Different and much more expensive tools are necessary to see if it can cause harm.

A range of other coronaviruses that mainly strikes the respiratory system have been spotted in feces. So has SARS-CoV-2. Different studies found the virus in 26% to 64% of the samples tested. One study said that despite being able to recognize the virus, the contents were busted. Two other studies found infective virus but didn’t say how much. To me, that says that on leaving the tank, there is some possibility that infective viruses are present.

Now, I have had that wonderful experience of using the toilet at the wastewater plant where the travel time to the system is measured in minutes, not days. Most people haven’t. Unless you happen to be Ed Norton of Honeymooners fame. The potential for exposure during the journey from the toilet to the treatment plant is minimal. If you have been following the literature on this lately, you may have seen a few articles about the presence of the virus in sewer systems. These articles are not about testing raw sewage for exposure potential. They are about seeing if testing sewage could be a way to track potential outbreaks and spread of the virus. This is an emerging and exciting field of research called wastewater based epidemiology (WBE). The tests are for pieces of packaging or contents — not to see if drinking the sewage would make you sick. It would, SARS-CoV-2 or not.

Other studies have tested survival time of the sisters, brothers and cousins of SARS-CoV-2 in tap water and primary effluent (the liquid fraction after primary treatment or settling of wastewater). Put a human or feline coronavirus in filtered tap water and stick it in the fridge and that virus will survive for months to a year. At room temperature, those viruses are gone in less than two weeks. Put them in primary effluent (far from tap water but a lot cleaner than wastewater plant influent) and they are gone in less than 3 days. Compare these to less fragile viruses and you’ll see a big difference. Polio virus (one that comes without the envelope) lasts over a week in effluent. This suggests that the potential for infective viruses, if they in fact do exist in feces, have minimal potential to make it to the treatment plant. Remember that influent is full of plenty of good and bad guys ready to devour these fragile envelopes.

Research is ongoing as to whether these viruses survive the treatment process and make it to the biosolids. This is being done at the University of Arizona at Dr. Ian Peppers’ lab. Here the exact SARS-CoV-2 virus is being looked at. It will take time to get the exact answer about this specific virus. However, remember that this whole treatment process was developed to destroy fecal-borne pathogens. The standards for land application of the biosolids are based on destruction of these pathogens. Testing is typically based on fecal coliform or salmonella. These are used as surrogates that are easy to test for the wide range of potential bad guys.

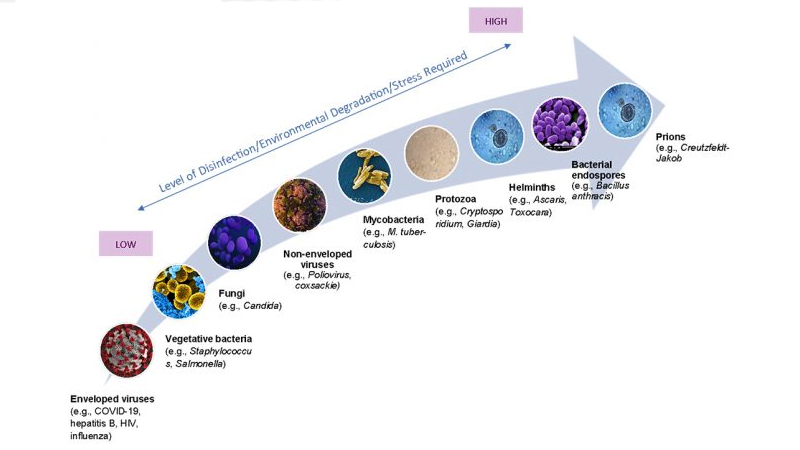

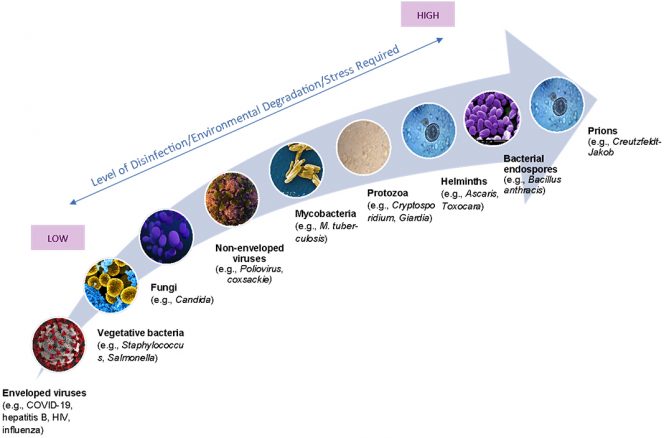

If you go back to the ranking of frailty described in the illustration in Part I (above) showing how fragile the different bad guys are, you can see that there are much tougher bad guys that these systems have been repeatedly shown to kill. Enteric virus concentrations are reduced from 5 to 10x with mesophilic anaerobic digestion and 100 to 10,000x by composting. These are the guys that start out in your intestines in the first place — so enter the wastewater system in much higher concentrations. They are also much harder to kill. Do we know for a fact that SARS-CoV-2 is killed during wastewater treatment? A hard-core scientist will say ‘no’ because that particular virus has not been tested under those specific conditions. A practical and well-informed scientist would say ‘almost certainly’ or not a chance in hell that SARS-CoV-2 would survive these systems if it got there in the first place.

If you go back to the ranking of frailty described in the illustration in Part I (above) showing how fragile the different bad guys are, you can see that there are much tougher bad guys that these systems have been repeatedly shown to kill. Enteric virus concentrations are reduced from 5 to 10x with mesophilic anaerobic digestion and 100 to 10,000x by composting. These are the guys that start out in your intestines in the first place — so enter the wastewater system in much higher concentrations. They are also much harder to kill. Do we know for a fact that SARS-CoV-2 is killed during wastewater treatment? A hard-core scientist will say ‘no’ because that particular virus has not been tested under those specific conditions. A practical and well-informed scientist would say ‘almost certainly’ or not a chance in hell that SARS-CoV-2 would survive these systems if it got there in the first place.

How About Compost And Compost Feedstocks?

How About Compost And Compost Feedstocks?

To even begin to worry about whether SARS-CoV-2 will be a concern for any stages of the composting process you have to have a very vivid imagination. First you have to figure out a way for the virus to get there in the first place. One potential scenario is that an infected and asymptomatic individual breathes really heavily on their yard trimmings or food scraps, or even worse sneezes or coughs on them. Another scenario where the virus can get into the food scraps is eating corn on the cob. The same saliva that is in the sneeze likely gets on the corn as you eat. Surfaces have been a big concern with this virus. There’s information out there that says the virus can stay intact and active on stainless steel for 2 to 3 days and 24 hours on cardboard.

This suggests the potential to get sick from touching a surface that someone had sneezed on (fomite transmission). We all know about washing our hands ALL OF THE TIME. This is why. However, no one really knows how likely transmission via surface contact actually is. The Centers for Disease Control recently redid its website on this, downplaying the surface pathway as a realistic transmission route. It remains a possibility, likely a very remote one. If you think about it, the potential for the virus to even enter the composting process through the pathways (scenarios) described above is pretty distant. Those involve indirect transmission — getting infected droplets on the food scraps and then having someone come in contact with those same scraps. Here the scraps are the effective surface. Then there is the question of how long that active virus would stay active.

You can use the information from wastewater treatment to put this into some perspective. A virus hanging out with very few friends and no enemies on stainless steel is a very different situation from that same virus hanging out with several billion bacteria and other microbes in a bag of compost feedstocks. Even before those scraps or branches reach a bin or pile, they are hosting a fair share of microbial activity. In other words, persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in these environments would be similar to persistence in wastewater — pretty low. As those moldy food scraps sit in the collection bin, the likelihood of survival goes down by the hour. Note: I am saying this based on the behavior of SARS-CoV-2 in dirty water. To my knowledge it has not been identified or studied in food scraps. This is very low on the list of things to study because it is a potential route for transmission only in the most vivid imaginations.

Exposure From The Pile?

Say your imagination is working overtime. The next big stretch for your imagination would be how you would come into contact with that miraculously surviving virus in the middle of the compost pile. Remember here that viral load is a factor. You don’t just need one of these bad boys to make you sick; more likely you need several hundred. You would have to lay your hands on these feedstocks and then touch your nose, eyes or mouth. The very thought should make you realize how unlikely this scenario actually is. The one potential route of transmission here is when you dump the bin of feedstocks, or assemble a compost pile. Would any surviving intact virus become aerosolized and you could inhale those bioaerosols?

Again here, we can look at wastewater and municipal biosolids. And again here, we can look at the research done by Ian Pepper. Many years ago, he and his team studied the potential for bacteria to travel attached to small particles as biosolids were being land applied. Class B biosolids has been treated to kill most, but not all, of the potential pathogens. Dr. Pepper and his crew traveled the country collecting air samples from land application sites. They found minimal to no risk even in cases where they spiked the biosolids with detector organisms (4 in 10,000).

The other common sense thing to remember here is that it is well understood that rotting food can make you sick. That is why almost all states require food scrap composting to reach time and temperature requirements for pathogen kill. If you work with composting, you should wear a mask and WASH YOUR HANDS.

In the case of SARS-CoV-2, the potential for compost feedstocks and the composting process to be a viable route of exposure is pretty much the same as for me to win the lottery with or without buying a ticket. Exposure to infected individuals in areas of low airflow (indoors) seems to be the primary route to infection. They don’t intend to be, no one does, but your fellow composters are who you need to be concerned about. That means work outside and if you are working closely with someone, wear a mask.

Sally Brown, BioCycle’s Senior Advisor and long-time Connections columnist, is a Research Professor in the College of the Environment at the University of Washington.