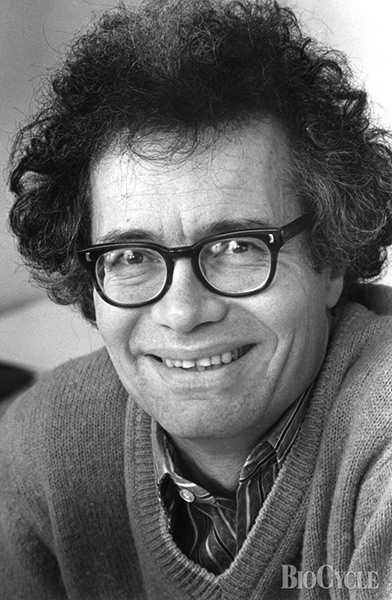

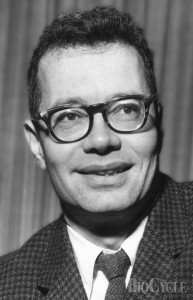

Remembering a man, and a life dedicated to communicating ideas and practices that sustain communities … and the planet.

Nora Goldstein

BioCycle June 2012, Vol. 53, No. 6, p. 34

Jerome (Jerry) Goldstein, Editor and Publisher Emeritus of BioCycle, and founder of The JG Press, Inc., died May 17, 2012. Reading his writings, letters and notes from the past 50-plus years, certain words keep popping into our minds, many starting with the letter “P”: Pioneer, Prolific, Positive, Prescient, Persistent, Passionate, Patient and Pugnacious. And then there’s a series of “C” words: Communicator, Collaborator, Consistent, Creative, Cooperative, Committed — and Community oriented in his actions, activism and thinking.

Above all, Jerry was a tireless advocate, an ecopioneer who used the tools of communication and networking to advance concepts that today fall into the catch-all category of sustainability. His style was to tell other people’s stories, to profile their projects and programs. He gave voice to their innovations and advances. And in the process, through his encouragement, promotion and support, Jerry worked to forge an industry around composting, organics recycling and anaerobic digestion that is very much alive and thriving today.

Jerry leaves behind thousands of pages of his writings — articles, speeches, editorials, book chapters, Letters to the Editor — that have influenced and shaped so many elements of resource conservation, soil preservation, composting, sustainable agriculture, renewable energy, recycling, locally grown and healthy food, and much more. But print and conference presentations were not his only communication outlets. Jerry testified before Congress and state legislatures, paid many visits to federal agencies and initiated campaigns — all to influence public policies that would benefit or might hurt composting, recycling, organic agriculture, renewable energy, food quality, energy consumption and urban and rural renewal.

For decades, people would comment that Jerry’s ideas were “ahead of his time.” And some still likely say that today. But here’s what is different. In communities around the globe, examples abound of Jerry’s life work — utilizing sewage sludge to fertilize soils, recycling papers, bottles and cans, composting food waste and other organics, using compost to build healthy soils, starting enterprises to deliver these services, creating nonprofits to carry out community initiatives, implementing green job training programs and more. Along the way, Jerry prodded and pushed, inspired and initiated, mentored and monitored, networked and nudged, created and communicated. And he always did it with a smile, a gentle manner and frequently, with humor.

This tribute to the Life and Legacy of Jerry Goldstein only scratches the surface of his influence and accomplishments. Just before deadline, we received a note from Gene Logsdon, a long-time cohort of Jerry’s (and another fabulous communicator). Gene had read an interview in Acres U.S.A. with Andre Leu, the new president of IFOAM, the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements, which began in 1972. Preceding the interview, editor Chris Walters gives a short history of IFOAM. He writes that the organization started in Versailles, France in 1972 “during an international congress on organic agriculture, organized by a French farmers’ organization and attended by the leading lights of the early organic movement: Walter Chevriot, Lady Eve Balfour, Kjell Arman, Pauline Raphaele and Jerome Goldstein.”

Wrote Gene when he sent us this mention in Acres U.S.A.: “Seldom have I seen Jerry get much public credit and yet he was right there moving mountains right along with the other major players.”

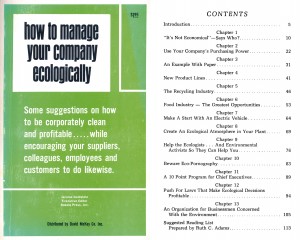

Managing Companies Ecologically

“How can you manage your company ecologically? Where do you start? What is involved? More to the point, is it possible to manage your company ecologically? Being an optimist and having decided to plunge ahead, I maintain that you can manage your company ecologically — or at least, in a much more ecological manner than in the past. There are many, many things that can be done — once you’re sensitive to the problems of the environmental crisis.”

So began the Introduction to “How To Manage Your Company Ecologically”: Some suggestions on how to be corporately clean and profitable …. While encouraging your suppliers, colleagues, employees and customers to do likewise,” written by Jerry in 1970. Chapter 1 was titled, “’It’s Not Economical’ — Says Who?” Like so much of Jerry’s writings, “How To Manage Your Company Ecologically” is as relevant today as it was over 40 years ago. One of our favorite passages starts with the headline, “Can GENERAL MOTORS Become GENERAL MASS TRANSPORTATION?” Here’s an excerpt:

“I talked to a small group of people the other night on ‘environmental living.’ Collectively, we tried to figure out what that term might mean. One thing seemed to be using your car less and using public transportation more. The problem — there was very little public transportation in the area and that was slow and expensive. So the evening was just talk.

“What needs to be done to get us to use public transportation? A high-speed ‘train’ that’s low-cost, comfortable, on-time and runs often. A law that prevents cars from going into the city unless it’s by special permit for medical reasons. That’s all.

“And how will that happen? Easy! Give General Motors the contract and the money to design and run the pilot line from Allentown to New York …. It’s self-defeating to contemplate the development of a mass transit system in this country without figuring out a way for General Motors and the other carmakers to profit from such a development. Once General Motors becomes General Mass Transportation, many separate pieces of the mass transit jigsaw fall into place. The lobbies, the politicians, the jobs, the stockholders, the banks, and so on and so forth …

“If GM is to become GMT, they’ll need some help from you. … Write your elected representatives; write the Chamber of Commerce; write the heads of corporations who should be involved in the development of a mass transit industry. If enough people want it, there’s got to be profits in the commercial development of such a system. But as long as you and I go along with the status quo, we’re helping to build more highways and more cars and more oil wells. It’s not so much a question of building cleaner cars. It’s easing us into a better way of getting transported. What’s good for GMT must be good for GM.”

In Business And The Triple Bottom Line

In January 1978, Jerry left Rodale Press after a 25-year career as Executive Editor of Organic Gardening & Farming and Executive Vice-President of the company. He started The JG Press, Inc., where he was joined by his wife, Ina Pincus Goldstein, and two daughters, Rill Ann Goldstein Miller and Nora Goldstein. The JG Press acquired the rights to Compost Science, which Jerry had edited since the publication was founded in 1960. The name was changed to Compost Science/Land Utilization. In 1981, the magazine was renamed BioCycle.

Prior to leaving Rodale Press, Jerry was working on a book about “careers to live by, jobs with meaning for you and the future.” While he wrote a number of chapters for the book, it wasn’t completed prior to founding The JG Press. Shortly after starting his company, Jerry began working on a new magazine concept, In Business. His inaugural editorial in the Premier issue in Spring, 1979, stated: “Originally, our editorial idea was to concentrate on ‘alternative’ ways of making a living on your own — businesses based on such things as solar energy, appropriate technology, natural foods, waste recycling, wood stoves, small-scale farming, community renewal. But as we delved more deeply into the world of small business, we came to realize how much every small businessperson has in common — how words like ‘alternative’ and ‘innovative’ and ‘counter-trend’ apply to the spirit of the people and the quality of the effort. That spirit, more than the kind of business itself, is the connecting fabric we see for shopkeeper and builder, for printer and repairman, for publisher and plumber …. for us all.”

Imbedded in Jerry’s vision for In Business, as well as BioCycle and The JG Press overall, was a concept that today is commonly known as the Triple Bottom Line — people, planet and profit. In May 1975, Jerry gave a speech at MacDonald College (part of McGill University) on soil management, organic waste utilization and the role of organic matter. Number 2 on his list of key messages: “Growing awareness of the interrelationship of social, economic and environmental concerns.” Loosely translated, social (people), economic (profit), environmental (planet).

Three years later, in a letter to a direct mail copywriter, dated July 10 1978, Jerry discussed his plans to launch In Business in early 1979. “The title is IN BUSINESS, with the subtitle “Working for the Future. … Major features will be case studies of businesses which we feel signify the “IN” in In Business — Innovative, Independent and “In,” in the sense of being relevant environmentally, socially and economically (in the long run).” Indeed, the eventual subtitle for In Business was the magazine for Sustainable Communities and Enterprises.

After 30 years of publication, The JG Press discontinued In Business with the December 2007 issue. In the editorial, Jerry wrote: “We have often reflected on the origins of In Business magazine — how we believed in the need for a publication that blends idealism with pragmatic decision-making, so that a business would be around for a long time to come. From the beginning, sustainability was an intricate link between ideals and pragmatics — that it just makes sense to recover resources, to grow and eat healthy food, to develop cars that are energy efficient and more.”

The Organic Force

Just about every day, we read or hear about local (and typically organically grown) food supplied by farmers on the perimeter of, or even in, the cities. In 1973, Jerry edited, “The New Food Chain: An Organic Link Between Farm and City,” which included essays by Wendell Berry, Jane Jacobs, Robert Rodale, Peter Barnes, Gene Logsdon and others. Jerry wrote the first chapter titled, “Organic Force.” In a July 2008 BioCycle editorial recalling “The New Food Chain” he said, “It is remarkable how this collection of ideas and insights are as timely today as they were in the late 1960s and early 1970s. It is startling to realize how we have come so far — organic food and agriculture is a multibillion dollar industry — and yet we have not come far enough, especially with regard to recycling organics back to soil.”

The following excerpts are from the chapter he wrote on the Organic Force: “The organic idea is basically a simple idea. It only takes a very few words to describe what organic means in the garden … or what it means on the farm. The explanation begins with the soil, gets into the compost heap, the natural cycle, the need to return garbage and sludge and wastes back to the land, the hazards of pesticides and artificial fertilizers to the environment, and the personal health benefits that go with eating quality, nutritious food.

“Yet more and more in the past few years, some grandiose concepts have been getting mixed in with the compost heap. Though it’s still the same old compost heap as it always was, in the 1970s the heap has come to mean something more. It still is simple. But now, instead of only rating the heap for its ability to make a soil fertile, we talk about it in such terms as social practice and harmony with the environment. To many people, it’s still just a pile of garbage and manure — true, a controlled pile on its way to becoming humus — but nevertheless, just a pile. To others, it’s a vision of a society in harmony with the environment …

“The organic concept is a forerunner of how an economic base can be given to idealistic concepts. Organic force is developing models for the survival of mankind. It shows how ecology can be blended into daily living without doing anything special. This organic force may very well be our best reason to be optimistic at this time.”

Green Jobs

In February 1976, Jerry wrote an article titled, “New Jobs In the Compost ‘Industry’: From compost toilets to composted sewage sludge, the modest-but-persistent developments in organic waste handling show the way to economic and environmental happiness.” The first paragraph of the article noted the importance of new job creation in an election year. “The job market is just as dismal just about everywhere you look now. One survey after another reveals shortages of employment opportunities in factories, in construction, in offices, in classrooms. From now until November, each and every presidential candidate will be answering questions about how, if elected, he will solve the problems of too few jobs.

“Several years ago a movie called The Graduate included a scene where the affluent executive whispered a one-word ‘secret-to-success’ to the young man in search of a career. The word was ‘plastic!’ Today, in recognition of the failure of the plastic strategy to bring us happiness (whether it be economic, social or environmental happiness), it may be the perfect time for someone to whisper a new seven-letter word into the ears of presidential candidates — C-O-M-P-O-S-T. …. Early indications are that compost is beginning to edge in front of plastic as the new growth industry. The signs can’t be seen on the stock exchange or in banking circles, but they are unmistakable…”

Jerry’s editorial in the April 2008 issue of BioCycle was titled “Good Green Jobs.” Here’s how it starts: “The Pennsylvania primary is a couple weeks away, and the airwaves and mailboxes have been filled with ads and literature from the three candidates vying for their party’s presidential nomination. The Clinton and Obama campaigns, in particular, continually highlight the role of “green jobs” in the country’s economic revival and environmental vitality. Employment sectors mentioned include energy and climate change. A mailing from the Obama campaign is a case in point. Under the heading, Economy & Jobs, it states: “Create new ‘Green Jobs’ through comprehensive energy independence and climate change plans.”

Several paragraphs later, the editorial sends the same message as Jerry communicated 32 years earlier: “The recycling, composting and renewable energy (from organics recycling) industries’ capability to create and sustain green collar jobs has been proven many times over. Recovering materials in the waste stream and converting them into high value products requires labor, and always has — especially when contrasted with landfilling and waste combustion. This is one reason that state governments regularly cite job creation as a significant accomplishment resulting from support of local recycling and composting programs.

“The companies listed in this issue’s Equipment and Systems directory are selling their technologies and services to public sector and private sector buyers who in turn are building the infrastructure to sustain composting, organics recycling and renewable energy programs. In turn, these programs and projects are creating and sustaining Green Collar Jobs. Now that is a campaign platform we can all support.”

National Soil Fertility Program

What are now BioCycle Conferences were launched in 1971 under the auspices of Compost Science and Organic Gardening & Farming. The Fifth Annual Composting And Waste Recycling Conference, April 25-26, 1975 was in Washington, DC. The opening speaker was Russell Train, Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency. In a summary of the conference, Jerry wrote: “In Washington, DC, the more than 300 registrants at the Fifth Annual Composting and Waste Recycling Conference: Composting, Fertilizer and Food Production, heard Russell Train, Environmental Protection Agency Administrator, call for an end to the status quo in waste disposal. “The use of organic waste in agriculture will become an economic necessity, rather than only an ecological nicety,” said Train, who added that the use of feedlot wastes and municipal sludges could satisfy about 6.5 percent of our national nitrogen requirements — at a dollar value of some $400 million annually to farmers.”

After discussing several other conferences held in Spring 1975 related to agricultural waste management, Jerry made the following suggestion: “After all that good talk on composting and organic waste recycling, the thought emerges of how vital it is for the U.S. to develop a National Humus Program. Humus becomes the critical yardstick by which to measure how seriously the excellent scientific research on wastes-in-agriculture is put into practice. …

“As we enter the Bicentennial Year, let’s suggest to our politicians and policy makers that we should include in the celebration the vow to build up the soil humus content of the nation with all kinds of organic wastes. Perhaps we can even get our candidates in 1976 to include a Humus Plank in their presidential platforms. …. Two hundred years should be more than enough time to begin laying the foundation for a permanent agriculture in the U.S. By translating organic wastes into soil organic matter, a major step will have been taken.”

Ten months later (February 1976) a “Special Action Issue” of Environmental Action Bulletin (EAB) was titled, “The National Soil Fertility Program,” expanding on the concept of the National Humus Program. The issue included a “self-mailer” that readers could use to send comments to the two Congressmen, Rep. Fred Richmond (D-NY) and Rep. James Jeffords (R-VT), who agreed to shepherd the program through the House Agriculture Committee. The self-mailer explained that The National Soil Fertility Program (NSFP) “shall be our national policy to encourage the return of soil-building organic matter to our country’s farmlands and to reclaim that land rendered unproductive by mining, abandonment, erosion and other consequences of our society’s climb to affluence.”

Rep. Richmond, the only member of the House Agriculture Committee at the time representing a totally urban constituency, noted that “the consumers definitely have a real stake in farming and farm policy. And that means a soil policy. The NSFP will directly affect urban residents. Fertile soils mean that less fossil fuel input is necessary to produce any given crop and, with the price of energy the way it is, this will translate into food at a moderate cost … We also must convince the city administrators to accept their place in the nation’s total food chain. In a truly national food policy, cities must recycle both solid wastes and sewage sludge back to the land.”

The wrap-up by Jerry on the NSFP is startling in its prescience: “The National Soil Fertility Program emphasizes that organic waste should be used under a priority system that puts composting first. To burn it is to condemn our nation’s soils to a continued loss of organic matter, increased soil erosion, and a loss of the vitality and life-sustaining force of those soils.”

We have had an association with Jerry since 1975 and have commented many times that this industry would not be here if it were not for his vision, foresight, and steady dedication and persistence to stay the course. He was truly a pioneer the likes of none which never will be surpassed. Because of Jerry’s guidance, mentoring, and example his vision will live on in his family’s capable hands.

Joan and Les Kuhlman, Resource Recovery Systems International, Inc.

Fast forward to February 19, 1977, when an update appeared in EAB on the NSFP legislation: “During 1976, major provisions of the National Soil Fertility Program were successfully inserted into the Democratic Party’s platform, with backing from then-candidate Carter. Now the program has reached legislative form …. The following wording is from Sec. 6, par. 56 of H.R. 75, sponsored by Rep. E. de la Garza (D-TX), a ranking member of the House Agriculture Committee. The bill is also known as the Land and Water Resource Conservation Act of 1977:

“[The bill calls for] investigation and analysis of the practicability, desirability, and feasibility of collecting organic waste materials, including manure, crop and food wastes, industrial organic wastes, municipal sewage sludge, logging and wood manufacturing residues, and any other organic refuse, composting or similarly treating such materials, transporting and placing such material on to the land to improve soil tilth and fertility. The analysis shall include projected costs of such collection, transportation and placement in accordance with sound, locally approved soil and water conservation practices.”

Bulletin readers were encouraged to send letters of support for H.R. 75. Wrote Jerry: “A deluge of letters will help ranking Ag Committee members see that our soils have a constituency willing to fight for their protection and health.”

In honor of Jerry Goldstein’s life work, we will bring back his campaign for a National Soil Fertility Program. Now, more than ever, his visions must become part of the permanent foundation of global sustainability.