Two-year pilot program to collect residential and school source separated organics is into its second year. This update reviews progress, challenges and next steps.

Bridget Anderson

BioCycle January 2015

Residents in the pilot program receive brown 13-gallon bins with a latching lid and wheels to collect organics (food waste and yard trimmings). Bins are placed on the curb to be serviced by the New York City Department of Sanitation (DSNY).

New York City’s (NYC) two-year pilot program to collect source separated organics — food scraps, food-soiled paper and yard trimmings — separately from refuse is now officially one year old. Through September 2014, this program, run by the NYC Department of Sanitation (DSNY), has expanded its service to approximately 100,000 households and over 350 schools, in addition to a few agencies and institutional sites. The goal of the pilot is to determine the viability of adding organics diversion as another source separated “recycling stream” to NYC’s waste management system.

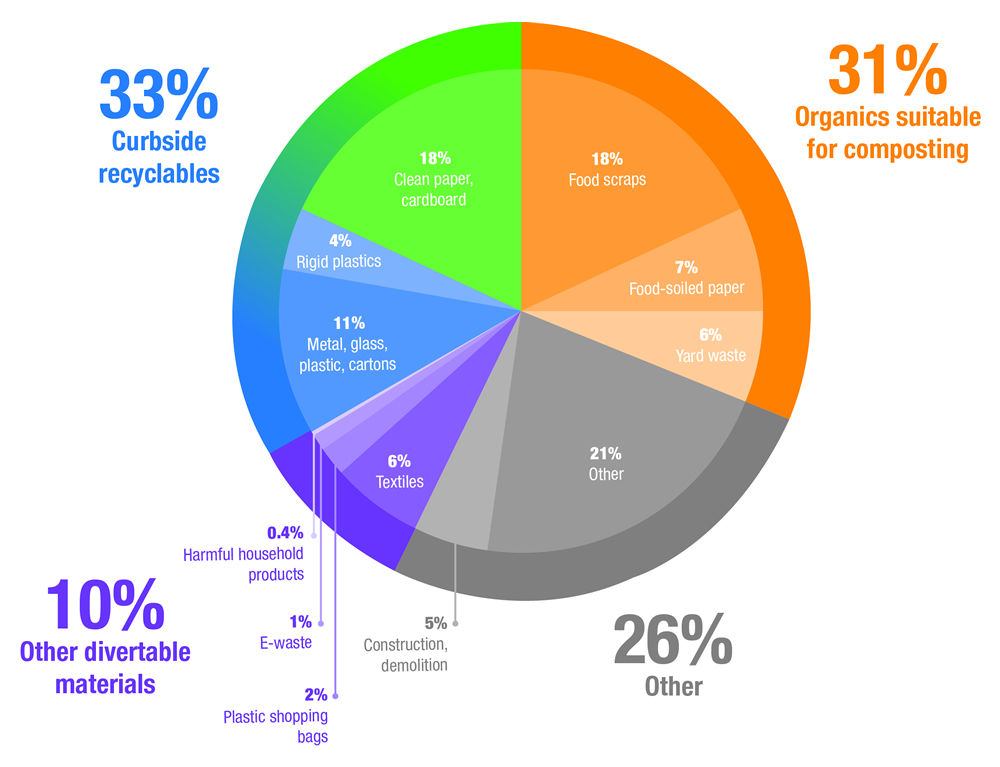

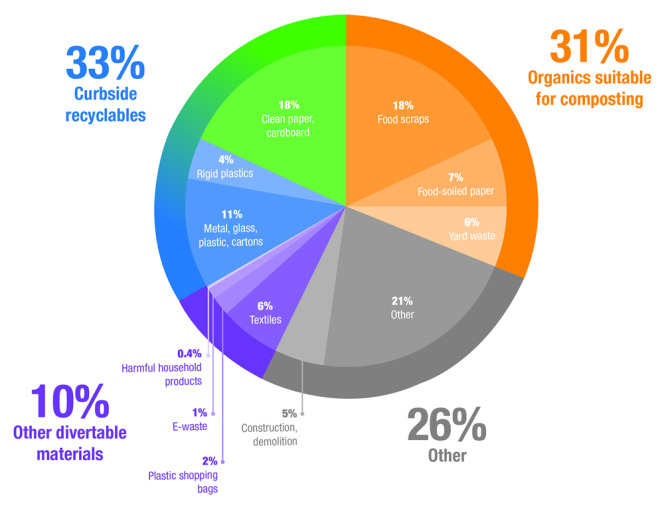

DSNY operates under a city mandate to achieve a 25 percent diversion rate by 2020. To date, the recycling rate is just over 15 percent. While NYC continues to work to increase recycling of traditional materials (paper and cardboard, and metal, glass, plastic and cartons), it cannot include recycled fill material and other items that are commonly counted as diversion by other cities in their diversion rate. After traditional recyclables, organic waste suitable for composting is the next largest portion of the waste stream, comprising about one-third of NYC residential curbside waste (see pie chart). Compost made from NYC’ source separated organics (SSO) has proven beneficial uses and is in demand both locally and regionally. These organics can be used to help achieve the city’s diversion mandates.

For any SSO management program to be viable, there needs to be front-end participation in sufficient quantity and quality, a sustainable collection mechanism, and back-end processing that can handle the composition and quantity of incoming loads of material. Each of these steps is critical to the overall system’s efficiency and effectiveness.

The passage of Local Law 77 of 2013 to conduct the pilot program pushed NYC to tackle the front-end participation while relying on existing processing capacity in the region. This means that inherently the back-end processing of the material would be limited by the facilities that exist and may or may not be efficient or effective during the pilot period. However, to build a long term system to process NYC organics, an understanding of what the material is going to look like, both in terms of quantity and composition (contamination), is required. Once the front-end feedstock can be forecasted, then the question becomes what the system (or systems) to manage that feedstock should look like, and if it can be done in a way that is cost-effective and environmentally preferable to alternatives.

While the residential pilot and school programs both collect organic waste and seek to maximize tonnage collected and minimize contamination, each has a very different set of operational considerations, challenges and opportunities. None of the challenges is unique to NYC, nor are they insurmountable with continued vigilance to make suitable tools available and to institute sufficient outreach and training, as well as to build the proper infrastructure to accommodate the anticipated behaviors.

Residential Pilot

Residents participate in organics collection on a voluntary basis; they are encouraged but not required to participate. After a year, the participation rate hovers at about 16 percent (increasing during leaf season, decreasing somewhat during the coldest winter periods). Through September 2014, the residential program has collected over 3,350 tons of material, raising the overall diversion rates of the participating populations between three and seven percent over traditional recycling only. People who participate are strong supporters of the program, and DSNY receives many comments about how, after recycling fully and separating organics, they have very little refuse left. DSNY also receives many inquiries from residents about when the service will come to their neighborhood.

DSNY trucks used to collect organics are wrapped with educational outreach messaging to promote the pilot program. This truck wrap reads, “Give your leftovers to plants, not landfills.”

New York City is the densest city in the country with a high diversity of housing stock. More than 40 percent of households are in apartment buildings with 10 or more units. About a quarter of households are single family homes or duplexes. The 10 current pilot neighborhoods are located in areas of the city with relatively low population density and housing stock that is comprised primarily of single-family homes and small apartment buildings. These lower density areas are more similar to the structure of cities with existing successful source separated organics programs than the high density areas of NYC. DSNY chose to try to replicate the strategy of those programs as a starting point for a NYC program.

Residents in pilot areas are provided with brown 13-gallon organics bins with a latching lid and wheels to set out organic material for collection by DSNY. (Apartment buildings with three to nine units receive one 21-gallon bin to share.) Each household is also provided with a small kitchen container to collect food scraps.

The majority of material collected from residences is yard trimmings (including leaves and lawn trimmings) and a significant amount of food waste. Apartment buildings primarily set out food waste. The contamination rate by weight is very low among the residential loads, though plastic bags, the most prevalent contaminant, are problematic for the processors.

Year two of the residential pilot will focus on increasing participation and managing the use of plastic bags, discussed more below.

School Program

DSNY partnered with the NYC Department of Education (DOE) in the 2012-2013 school year to roll out organics collection in public schools. A small handful of private and parochial schools also volunteered to participate. Through September 2014, the school organics program included about 350 schools, and collected over 3,160 tons of material. (In October 2014, the program more than doubled to include 720 schools; results are not yet available.)

The schools in the program vary widely in the quantity and quality of material set out for collection. The private schools — and a minority of the public schools — diligently separate food waste from recyclables and refuse in the cafeterias and kitchens and set it out on the proper collection days. They also find it a useful educational opportunity.

For the majority of public schools, however, the program has been a heavy lift both for the custodial staff and for the students, teachers and administrators. In particular, educational facilities that house multiple schools and large student populations struggle to coordinate operations, train and motivate staff, and get students to properly sort their organic waste in the limited timeframe and high traffic of the lunch period. Traditional recycling is also a challenge for these schools.

DOE schools in the program are required to participate, whether or not they want to, which provides insight into the high levels of contamination in the organics loads collected by DSNY. While relatively low by weight, foam trays, plastic cutlery and plastic wrappers are the largest contaminants in the school organics loads. Many loads are indistinguishable from refuse. DOE is working to procure compostable trays, serviceware and bags, but in the meantime, the labor needed to sort the organics from the contamination has been a heavy burden for the processors.

An organics load from the DOE schools participating in the NYC pilot program shows high levels of contamination. Foam trays, plastic cutlery and plastic wrappers are the top contaminants

in the loads.

Year two of the school program will focus on strengthening DOE’s ability to institute systemic changes, such as the switch to compostable trays, and improve training.

Organics Processing

As mentioned, DSNY has had to rely on existing outlets to handle and process the organics loads from the residential pilot and the school program. About a quarter of the material is processed at a DSNY-managed composting facility on Staten Island, one of NYC’s five boroughs. This facility, currently permitted to take food waste on a limited pilot basis, primarily composts leaves and woody material using open windrows. DSNY pays its contracted vendor, WeCare Organics, to manually separate contaminants from the organics loads, a process that takes multiple hours daily.

For a short period, a small portion of the school program material was delivered to a Waste Management, Inc. (WMI) facility in Brooklyn, where the organic fraction was turned into a slurry and taken to the Newtown Creek wastewater treatment plant run by NYC’s Department of Environmental Protection for addition to the plant’s anaerobic digesters (AD). WMI staff manually removed not only inorganic contamination but also the woody and paper portions of the organic material, as this was not acceptable in the AD system. After the testing period, it was determined that pure food waste, such as what might come from restaurants, would be a more appropriate target feedstock for this facility.

The remaining material was trucked to the Wilmington Organics Recycling Center (Peninsula Compost) in Delaware, the only other facility in the region with the infrastructure to preprocess the material to remove contaminants. The closing of Peninsula Compost in October 2014 has led NYC to use other regional composting facilities. To date, while these facilities have capacity to take NYC’s organics, they do not have infrastructure to do extensive presorting to remove large amounts of contaminants, such as exists in the school loads.

DSNY is working on both front-end and back-end solutions to minimize and remove contaminants. On the front-end, finding a good “carrier” for food waste that is not a plastic bag has been one of the primary challenges to the residential program. New Yorkers do not uniformly use bins or carts to manage their refuse and recycling; rather, they use bags. So the task of managing the brown bin — keeping track of it and keeping it clean — is new to many and considered a barrier to participation for some.

Though the pilot program has pushed the strategy of going “bag free,” there is a strong perception that plastic bags are the best mechanism to keep the process of organics separation “clean and tidy.” While compostable bags are sold in stores as an alternative to traditional plastic bags, and pilot areas received either sample compostable bags or coupons to purchase compostable bags, a majority of residents do not want to pay extra for these bags and prefer to line their bins with clear plastic recycling bags or use the shopping bags that they receive for free, even though the program prohibits them. DSNY is increasing its education and training opportunities for residents to learn best practices for organics recycling.

On the back-end, compostable plastics break down at the processor. However, unless the entire system switches to compostable, organics loads mixed with traditional and compostable plastics will still require plastic to be sorted out before composting. Preprocessing equipment and technologies exist that can handle both the residential and school organics, and DSNY is determining the siting opportunities and financing options to incentivize development of such infrastructure.

Year two of the pilot (and beyond) will focus on improving the front-end contamination, determining preprocessing options, and planning for long term processing needs.

Bridget Anderson is the NYC Department of Sanitation Deputy Commissioner for Recycling and Sustainability.