Marsha Johnston

King County, Washington’s display at a farmers market, which included information on how to keep the produce being purchased fresh, was popular and effective to recruit participants for its Food: Too Good To Waste (FTGTW) Challenge.

Photo courtesy of King County Solid Waste Division

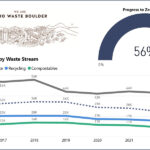

Modeled after the United Kingdom’s “Love Food Hate Waste” program, the West Coast Climate & Material’s Management Forum’s (Forum) Food: Too Good To Waste (FTGTW) initiative created a toolkit with strategies and tools to guide households on how to reduce wasted food. The Forum is a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency-led partnership of western cities and states. The FTGTW initiative is being tested in pilots around the country. Seventeen FTGTW pilots in 15 communities are “Taking The Challenge,” using community-based social marketing (CBSM) to recruit, retain and provide consumers with tools and strategies to reduce food waste. The pilots took place from fall 2012 through 2014.

CBSM, which involves direct contact with people to drive behavioral changes through community initiatives, was used in the FTGTW campaigns to stress 5 key waste prevention strategies:

- Get Smart: See how much food and money you’re throwing away. This involves doing a baseline household measurement to understand how much food (and money) participants were throwing away.

- Smart Shopping: Buy what you need.

- Smart Storage: Keep fruits and vegetables fresh.

- Smart Prep: Prep now, eat later.

- Smart Saving: Eat what you buy.

The campaigns ranged from small pilots to broad-scale media campaigns and used a variety of outreach, engagement tools and recruitment methods, including tables at farmers markets, food film nights at public libraries and direct letters. Campaign partners included local solid waste departments and nonprofits with broader missions. Implementation costs ranged from several thousand dollars to over $100,000.

The U.S. EPA hosted a webinar in February about the pilots and the findings. The initiative’s primary objective, explained Ashley Zanolli with U.S. EPA’s Region 10 office and Forum co-leader, is to educate consumers that the best environmental strategy for food waste is to avoid it in the first place and to provide the tools to do so. Viki Sonntag, founder of Ecopraxis, an economist and FTGTW’s lead researcher noted, “Overall, the campaigns were moderately to highly successful. Some of our organizers, based on past experience, thought behavior change programs might be hard, but the CBSM approach proved both great receptivity to prevention behaviors and that people find it easy to make these changes.”

Most surprising, Sonntag added, was the extent to which measuring household food waste activated participants’ natural tendency to avoid waste. Further, the FTGTW Challenges proved highly effective, with a post-challenge survey showing 93 percent of participants saying they were more aware of food waste and 96 percent strongly agreeing or agreeing that they would continue to use the tools. In fact, Sonntag noted, only multiple tools for different audiences, not media campaigns, are sufficient to reinforce behavioral change.

Furthermore, the pilots produced greater reductions in preventable waste, which is defined as edibles that are either spoiled or simply discarded, than in total waste, which can be either edible or inedible. By weight, campaigns reduced preventable waste by between 11 to 48 percent and by volume from 27 to 39 percent. Maximum total waste reductions by weight and volume were 30 percent and 27 percent, respectively. Some pilots recorded slight increases in total waste, likely due to high weights and volumes of corn husks and watermelon rinds during summer pilots in Iowa, for example. Overall, Sonntag said the pilots proved that it is possible for a household to reduce preventable waste by over 50 percent by weight, which they estimate equates to a 20 percent reduction in total food waste.

Among the challenges to successful food waste campaigns, organizers found it difficult to identify networks through which to engage young adults, and that adding composting to the food waste prevention objective could be complicated. “A lot of the people had already been exposed to community education about composting, so when a few campaigns tried to introduce FTGTW, things got kind of muddy,” Sonntag said, adding that often participants were less clear about the benefits of food waste prevention as compared to composting.

Iowa City, Iowa held an open house as part of its FTGTW Challenge to enable face-to-face contact with participants, who received a kitchen scale (lower right), countertop collection bin and compostable bags.

Photo courtesy of Iowa City.

Case Studies

The February webinar hosted by U.S. EPA also featured three of the FTGTW campaigns — King County, Washington, Iowa City, Iowa, and a pilot coordinated through the Rhode Island Food Policy Council. Of the three, King County was the FTGTW veteran, having run a small pilot in 2012, and a big media campaign in 2013 that produced a series of how-to videos with a local chef and grocer, PCC Natural Markets. “King County really hit their stride in this third year,” noted Sonntag, of the county’s campaign last summer, “engaging different groups, training master composters, doing peer-to-peer networking and tabling at farmers markets.”

Karen May, program manager at King County Solid Waste Division, said its farmers market display was popular and effective for recruiting FTGTW Challenge participants. “We featured vendor produce with tips about how to keep their food fresh,” May explained. “We also had in-depth, quality conversations with people about food waste prevention, distributed Fresh Paper samples [a product that retards produce spoilage], stickers and FTGTW shopping lists, and used an apple-shaped chalkboard where people noted food waste prevention actions they agreed to take, which we photographed and posted on our Facebook page.”

Ultimately, 53 King County households completed the 4-week FTGTW Challenge, resulting in a 75 percent retention rate, compared to around a 50 percent average among all of the pilots. “We believe we had a healthy retention rate because we offered incentives and prompted participants weekly with emails, offering tips, encouragement and the chance to win a prize each week, such as clear glass food storage containers, a white board for the fridge, etc.,” added May.

While all campaigns reported that recruiting participants was more difficult than they imagined, Iowa City had the highest recruitment rate of 17 percent, getting 52 out of 300 homes in five neighborhoods to participate in its 6-week pilot last June-July. “We spent a lot of money on outreach and education, which is probably the reason for our higher participation rates than other communities,” said Jennifer Jordan, recycling coordinator for the city, reporting that staff time and “education” accounted for over $10,000 of the program’s $11,104 total cost.

To get people to return their pre- and post-pilot surveys, Iowa City sent letters with postage-paid return envelopes, left door hangers and sponsored an open house in each neighborhood. The open house provided face-to-face contact with participants, who received a kitchen scale, countertop collection bins and bags and information packets.

Iowa City’s most interesting findings included: Gardeners had a higher amount of food waste than non-gardeners; Vegetarians and vegans had double the amount of waste than omnivores; and Participants rated Smart Shopping the easiest and Smart Prep the hardest. Were the City to do the FTGTW Challenge again, Jordan noted they would reach out to more than the 300 homes and do longer baseline and measurement periods.

With the smallest survey population of ultimately 50 people, Rhode Island’s four test groups reduced the most preventable food waste, between 48 and 70 percent during its 6-week pilot. Dave Rocheleau, who was head of the Healthy Environment Working Group of the Rhode Island Food Policy Council, said the working group was already focused on zero waste when it learned of FTGTW. A chef, Rocheleau taught participants how to cook with maximum yield, which he said was “quite successful.”

The Council translated all of the FTGTW tools into Spanish and targeted one Spanish-language community. It also partnered with the Providence Housing Authority’s low-income community. In addition, it consciously recruited “friendlies,” as “we wanted people who would give brutally honest feedback,” Rochereau explained.

All three pilot locations plan to continue FTGTW initiatives in 2015. May noted King County will continue farmers market outreach, encourage the Challenge through local networks and pilot an Imperfect Produce campaign to enlist supermarkets to sell misshapen or off-spec but still-nutritious produce to customers at a discount. King County’s total budget for this year’s program is $91,000.

Iowa City plans further FTGTW outreach, including monthly tabling at farmers markets, and “Friday Food Films” at the Iowa City Public Library and open houses. It also is evaluating the cost-benefit of a residential curbside organics collection program. Rhode Island’s next steps for 2015, said Rocheleau, are pursuing funding, doing a workshop series, training trainers, continuing to work with the Housing Authority and adding a composting component.

The EPA notes that the Food Too Good to Waste toolkit is scheduled to be posted to EPA’s national Sustainable Materials Management website by this summer. At that point, FTGTW will become a tool of the Food Recovery Challenge, a U.S. EPA program that partners with organizations and businesses to prevent and reduce wasted food.

Marsha W. Johnston is Principal of Earth Steward Associates in Arlington, VA and a Contributing Writer to BioCycle.