Rhys Roth

This article is based on excerpts from a report, Infrastructure Crisis, Sustainable Solutions: Rethinking Our Infrastructure Investment Strategies by Rhys Roth, Director, Center for Sustainable Infrastructure at The Evergreen State College. It was released in November 2014. Meet Rhys Roth at the Opening Plenary of BioCycle’s 29th Annual West Coast Conference, April 13-16 in Portland, Oregon. www.BioCycleWestCoast.com

This article is based on excerpts from a report, Infrastructure Crisis, Sustainable Solutions: Rethinking Our Infrastructure Investment Strategies by Rhys Roth, Director, Center for Sustainable Infrastructure at The Evergreen State College. It was released in November 2014. Meet Rhys Roth at the Opening Plenary of BioCycle’s 29th Annual West Coast Conference, April 13-16 in Portland, Oregon. www.BioCycleWestCoast.com

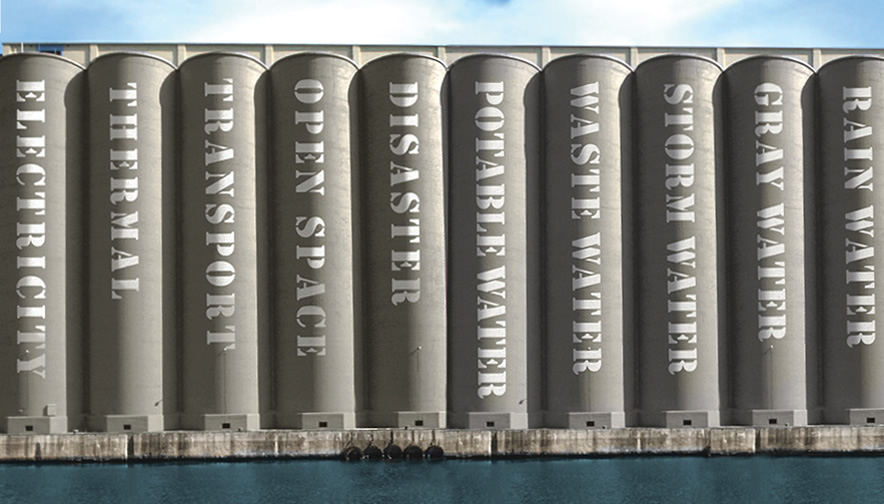

Today, for the most part, our communities’ infrastructure systems are developed and managed separately, by separate utilities and agencies. Sustainable infrastructure, on the other hand, blurs boundaries between our energy, transportation, water and waste systems to implement complementary strategies that benefit more than one system. Among our most important, and difficult, challenges will be reforming institutions and their funding mechanisms to enable and incentivize integrated, whole-system solutions that benefit our communities the most.

During the first half of 2014, the Center for Sustainable Infrastructure (CSI) at The Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington, formally interviewed 70 of the Pacific Northwest’s top infrastructure innovators and thought leaders about how to achieve a future for the region and beyond where sustainable, resilient and affordable infrastructure systems provide vital services accessible to all, supporting healthy, prosperous, beautiful, and cohesive communities. Distilling the prevailing themes and key insights, the purpose of the report — “Infrastructure Crisis, Sustainable Solutions: Rethinking Our Infrastructure Investment Strategies” — is to provide inspiration and guidance to the region’s current and future infrastructure leaders, policymakers and change agents.

Integrated Solutions

Integrated solutions benefit more than one infrastructure system, plus deliver a generous range of other economic, social and environmental benefits. Integrated solutions take many forms, and require breaking through institutional silos (Figure 1). “Conventionally, we design infrastructure within its silo, rather than looking for opportunities to optimize between systems,” says Aaron Berg, President and Founder of Blue Tree Strategies. Water utilities, for example, might not consider tapping their pipe infrastructure for gravity-fed energy generation, even though this will slow the water’s flow downhill which, at certain times of year, is valuable for the utility.

Another example: shifting to electric vehicles. “The transportation and electric industries tend not to talk to each other,” says Angus Duncan, President of the Bonneville Environmental Foundation.

Integrating infrastructure systems also closes loops in communities. “In nature nothing goes to waste,” explains Steve Moddemeyer, Principal with CollinsWoerman and a leading advocate for closed loop infrastructure systems. “Instead waste becomes the feedstock for other systems.” He describes closing loops in urban systems as “identifying productive reuse of waste products at the smallest scale reasonable.”

Moddemeyer also points out that roughly 30 percent of a typical city is covered by streets and sidewalks, so the public owns, via the street right-of-way, much of the community’s most valuable urban real estate. Beneath those public streets lie an assortment of critical infrastructure pipes — for sewer, water, wastewater, storm water, natural gas, and sometimes electricity and telecommunications cable. If a single business controlled several systems concentrated on its real estate, it would be unthinkably bad management not to closely coordinate maintenance activities across business lines. Yet the infrastructure upon and under the public’s wealth of high value real estate is managed by separate utilities and agencies, each with their own mandates, budgets, planning and work cultures, making close coordination the exception rather than the rule.

Investing In Nature

According to the World Resources Institute (WRI), over the next 15 years, $10 trillion will be invested globally in water infrastructure alone (WRI, 2013). “Natural infrastructure,” an interconnected network of natural areas, open spaces and constructed features such as green roofs, green streets, bioswales, and constructed wetlands, planted in rich water-retaining composted soil, is poised to make a major contribution. Natural infrastructure can reliably augment the functions of conventional engineered systems (“gray infrastructure”), often at much lower cost by shrinking the need for water filtration plants, reservoirs, chillers, and dikes and levees (Gartner, 2013).

“Restoring natural processes in coordination with built infrastructure,” says Callie Ridolfi, President of Ridolfi Inc., an engineering firm specializing in sustainable practices, “can improve performance, enhance adaptive capacity and resilience, and create cost-effective infrastructure solutions.” The WRI studied six U.S. cities, which saved 60 percent on their water infrastructure investment using natural infrastructure strategies. In addition, these systems increased the longevity of conventional systems (WRI, 2013).

Green storm water management tools, such as bioswales that use compost in the engineered soil mix, are poised to make a major contribution to sustainable water infrastructure over the next 15 years. Photo courtesy of Seattle Public Utilities

While investments in natural infrastructure can save money on water infrastructure, rebuilding natural systems simultaneously spreads benefits throughout the community. Important community co-benefits of natural infrastructure extend from storm water and flood management to protection of clean water supplies, local climate control and energy savings, biocarbon capture, cleaner air, improved habitat for a variety of native species, and enhanced beauty and comfort in urban communities.

The co-benefits of investing in nature are not merely nice add-ons but integral to Oregon Metro’s $15 million Nature in Neighborhoods Capital Grants program, managed by Mary Rose Navarro. “If this grant program simply focused on urban nature, we would be failing to capitalize on the opportunity to fully invest in our communities,” says Navarro. “Projects need to be thoughtfully and creatively conceived to achieve multiple benefits such as economic development, local job creation, workforce development, and community cohesiveness.”

Smart Energy, Smart Water

Saving energy saves water, as does switching from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources. Nuclear, coal and gas (especially deep shale gas) energy facilities require enormous amounts of water — 48 percent of all U.S. water withdrawals in 2000, according to U.S. Geological Survey (U.S. DOE/NREL, 2006) — while wind and solar PV require very little water. A typical coal plant, for example, can require seven times more water in its lifetime than the annual consumption of the entire city of Paris, according to Michael Liebriech, CEO of Bloomberg New Energy Finance (Liebreich, 2012). Reliance on huge supplies of cool water is a significant risk factor for these power plants, as well as the Northwest’s hydropower facilities, into the future, especially as climate change impacts hydrologic patterns.

Saving water, in turn, saves energy. Drinking water and wastewater systems alone consume an estimated 3 to 4 percent of all energy in the U.S., resulting in 45 million tons of greenhouse gas emissions, according to the U.S. EPA (USEPA, 2013). A recent study by the Pacific Institute of the potential for water-use efficiency in drought-stricken California found that solutions harnessing existing, cost-effective technologies in four areas — urban, agriculture, water recycling and storm water capture — can save roughly a third of current statewide demand (Pacific Institute, 2014).

Water systems consume a lot of energy, but can also be tapped for energy. For example, wherever water flows downhill through pipes there is potential energy, and new miniturbine technology, such as that pioneered by Portland-based Lucid Energy, could make it profitable for water utilities to tap it. Wastewater utilities are increasingly harnessing methane generated at their treatment plants via anaerobic digestion, as well as deriving value by transforming the carbon and nutrient-rich biosolids that are left over after the treatment process into a marketable, biologically-rich soil amendment.

Forward-looking communities are also pulling out heat embedded in the wastewater flowing through sewer pipes to meet hot water and space heating needs. A recent feasibility study prepared for the Washington Department of Corrections found sewer heat recovery technology could save $250,000 a year in diesel fuel costs at the Clallam Bay Corrections facility, enough to pay back the capital and installation costs in less than four years (www.sewageheatrecovery.com/; International, 2014).

Wastewater utilities are increasingly harnessing methane generated at their treatment plants via anaerobic digestion as well as deriving value by transforming the carbon and nutrient-rich biosolids into a marketable soil amendment.

Photo courtesy of City of Gresham

Paying The Bill

We clearly have abundant opportunities to change how we spend and invest in our infrastructure to develop smarter, more affordable, sustainable and resilient systems. So why is sustainable infrastructure still the exception rather than the rule? The thought leaders interviewed for this report identified many reasons why the status quo is tenacious. One example is the typical approach to awarding infrastructure construction contracts to the lowest bidder. “If your job as a contractor is to respond with the lowest bid for construction, you’re not incentivized to care about minimizing operating expenses over the 30-year lifespan,” says Chris Taylor of the West Coast Infrastructure Exchange.

Infrastructure finance expert Karen Williams of Carroll Community Investments, LLC adds, “Traditional procurement leaves the vast bulk of the risk with the public owner, even though the owner is not in primary control of design, construction, and long-term performance risks.” Williams notes that these risks discourage innovation: “Agencies usually avoid innovation in favor of long-proven methodologies, even if the innovative solution might result in a better performing product.”

The basic business model by which our utilities and infrastructure agencies are funded may pose a fundamental barrier to innovation. Currently, revenues to pay for road, water, electricity and waste infrastructures depend heavily on rates or taxes paid by customers based on sales volume. The more resources consumed or waste produced, the more revenue is generated to pay for the capital and O&M costs of infrastructure services, an approach that has worked reasonably well in the past. The shift toward sustainable infrastructure investments, however, that actively encourage conservation, distributed systems, and alternative technologies can shrink sales of gasoline, water, and power, and reduce solid waste tipping fees. “This creates a profound disincentive to fully investing in affordable and sustainable infrastructure solutions,” he adds.

“As policymakers and regulators, we absolutely have to crack this nut.”

The electricity sector has been leading the way in “decoupling” utility revenues from total throughput, so that utilities can collect revenue from their smart, cost-effective investment in conservation services, even though conservation will reduce sales of their primary product. “The utility of the future will predominantly bill for services instead of volume,” notes Steve Moddemeyer of CollinsWoerman.

Most thought leaders cited institutional silos as a key challenge, including simply communicating across silos. “People coming from different fields and perspectives can speak almost a different language,” says Ecotrust’s Brent Davies. Funding channels for infrastructure can discourage integration as well. “The funding programs are pigeon-holed, which stifles innovation,” notes Chris Watchie, Director of Trans-Watch. Divided responsibilities can mean it is no one’s job to develop integrated strategies to optimize the whole system. As the Bullitt Foundation’s Steve Whitney points out, “You’ll have a watershed with 14 jurisdictions and 25 taxing districts. It makes it really, really hard to do anything at scale.” Another reason it is difficult to comprehensively rethink our infrastructure systems is “the diminishing capacity of government to finance infrastructure, and to be the primary driver establishing vision and direction to do big bold projects,” says Tony Usibelli, Director of the Washington State Energy Office.

Current tools also do not reflect the full range of environmental costs and benefits of our infrastructure choices. The lack of a price on carbon emissions is a leading example of an “external cost” that is not reflected on the economic balance sheet today. “Strong climate policy, including putting a cap and price on carbon emissions, accelerates innovation on the ground by sending the right market signals to level the playing field with the fossil fuel industry,” says Eileen V. Quigley, Director of Strategic Innovation at Climate Solutions. “Just look at the groundbreaking innovations in energy efficiency and renewable energy in states with strong climate policy such as California and Massachusetts.”

Similarly, the health benefits of sustainable infrastructure choices, such as cleaner air and water, are not adequately weighed by our economic assessment tools, nor are the benefits of healthy natural systems. Valuing the benefits of natural assets correctly is essential to enable financing to flow toward protecting and enhancing these systems. As Earth Economics’ David Bakter points out: “We need to change accounting rules so that green infrastructure’s value is fully recognized on the bottom line of the balance sheet. Right now its value as an asset is counted as zero.”

Ten Guiding Principles For Innovation

Distilling the prevailing themes and key insights from the thought leader interviews, the Center for Sustainable Infrastructure offers infrastructure agency leaders, elected officials, and community planners the following 10 guiding principles for sustainable infrastructure innovation.

Go For The Triple Crown: Fiscally Sound, Resilient And Sustainable

There are growing constituencies for infrastructure change. Some are focused most urgently on how we can finance a ballooning “infrastructure deficit” and deal with increasing costs for operations; others on making our systems quicker to recover in natural disasters and emergencies; and still others on the crucial environmental performance of infrastructure systems. The good news is that there is a rich array of opportunities and new infrastructure strategies that offer strong and simultaneous affordability, resilience and sustainability benefits.

Consider Broader Alternatives

Smart investors seriously consider alternatives as part of their due diligence. Before committing real money to business-as-usual infrastructure projects and programs, smart public infrastructure decision-makers consider it a wise investment to draw on the best innovations out there to thoroughly compare a portfolio of options that provide the most benefits for the cost — including cost-effective investments in reducing demand.

Encourage Silo-Busting

Virtually all our communities are heavily invested in multiple infrastructures — everything from streets and bridges, to electricity, natural gas and heating services, water supply, sewers and storm water, and waste collection, recycling and disposal. Very often planning and investment for these systems are departmentalized, and as departments grow they often grow compartmentalized, too, which can lead to missed opportunities for multiple benefits and increased overall value. When we consider these systems as parts of a larger interacting whole, valuable synergies emerge where, for example, waste from one system can become a resource for another.

Build A Better Business Case

Once infrastructure planners narrow the project or program options to the top few, it’s crucial to weigh the full benefits and costs, and to do it on a life-cycle basis — meaning for not only construction but also operation and maintenance over time. But benefits and costs should not be limited to the department charged with managing one particular infrastructure system. Smart investments will save money, manage risk, and accrue benefits to other departments, and serve broader community goals. Considering capital and operating budgets simultaneously is key. The full range of benefits, costs and risks — to the department, to government as a whole, and also to the broader community — all need to be carefully evaluated and documented with well-designed business cases to compare investment options one against the other.

Educate, Engage and Inspire

Infrastructure systems are the most costly and enduring capital assets any community joins together to invest in. With legacy systems often aging and under stress, and with serious constraints on the public purse, citizen support for needed infrastructure investment is increasingly crucial. Earning that support requires effective communication and public engagement, which in turn must rest firmly upon a compelling vision of where we are going, why it’s so important, and why the strategy is smarter and more cost-effective than the standard way of doing business.

Build Community Prosperity

Infrastructure spending is paid by and benefits the whole community. It is widely recognized as a job generator and important to local business and economic vitality. Evaluating the community’s strategies for infrastructure in light of its economic development goals can reveal opportunities and strategies to in-source infrastructure jobs and lift up segments of the community too often left out. Higher education can build the critical pipeline of local talent by designing technical training and advanced degree programs that build skills important to sustainable infrastructure.

Choose For A Changing World

Infrastructure decision-makers must increasingly be future-casters. Capital projects this year will often be paid for over many years and in operation even longer. It’s vital to make sure we are building infrastructure systems well-adapted to our changing world — from technology revolutions to major environmental stresses, from shifting living patterns to changing lifestyles and demographics as one generation ages and the next one grows up.

Integrate Smart Systems

Today people carry devices in their pockets packing information, communications, and monitoring capabilities unimaginable a generation ago. Advanced technologies are transforming many industries, but for our infrastructure systems, unrealized opportunities abound. Infrastructure managers, tapping private sector expertise, can harness low cost monitoring and real-time management technologies to improve service and achieve cost-saving efficiencies.

Partner With Nature And Enhance The Community

A community’s most beloved places are often where natural features and beautiful structures are richly present. Increasingly, water, wastewater and storm water utilities find that investing in natural systems can provide increased functionality and save money compared to relying solely on traditional hard infrastructure approaches. And when conventional infrastructure investments do make the most sense, investing in beautiful design can turn an “ugly” industrial-looking facility into a valued community asset.

Value Capacity And Expertise

Successful infrastructure innovation that delivers long-term cost savings and a host of better outcomes requires sophistication and deep expertise. Centers of expertise can help ensure local agencies don’t reinvent the wheel and access the best data, tools, policies, and case studies from the broader marketplace. New procurement strategies may also be key: Rather than staging the typical ‘low-bid war’ to hire the cheapest contractor, new approaches can incentivize private sector innovation and sustainability, reduce risk of cost overruns borne by the public, and reward quality performance over time. Within organizations, translating a new vision into the day-to-day priorities of staff may require revamping job descriptions, performance metrics, and training.

Implementing The Principles

Two ideas emerged from the thought leader interviews for implementing these principles in a comprehensive way:

- Community Leaders: Develop a 10-year Sustainable Infrastructure Strategic Plan for the community that encompasses the various infrastructure systems. Because infrastructure is central to the future of a community’s economy, fiscal health, sustainable land development and quality of life, creation of an infrastructure strategic plan can provide a central focus aligning both implementation efforts and the various other local plans. It can also provide a platform for the agencies and utilities managing different infrastructure systems, both local and regional, to harmonize their plans with the community’s goals and aspirations. “This kind of planning answers the questions, ‘are we doing the right project?’ and ‘are we doing the project right?’,” says infrastructure finance expert Karen Williams.

- Infrastructure Managers: Adopt the disciplined practices of Sustainable Asset Management. Traditional asset management tools uncover investments that control the total cost of ownership over the lifecycle of the system’s infrastructure assets. Sustainable Asset Management adds two crucial elements to the discipline: Integrated strategies that reveal solutions benefiting more than one infrastructure system, and “Triple Bottom Line” metrics that measure not only financial factors, but also important social and environmental considerations.

References

- Gartner, Todd, “A Critical Moment to Harness Green Infrastructure – Not Concrete – to Secure Clean Water,” World Resources Institute. January 10, 2013. www.wri.org

- International Wastewater Systems, Feasibility Study Report, Project: Clallam Bay Corrections Center, Clallam County (WA). Submitted: September 22, 2014. www.sewageheatrecovery.com

- Liebreich, Michael, “Water May Top Up the Case for Renewables,” VIP Briefing, Bloomberg New Energy Finance, September 27, 2012; www.bnef.com

- Pacific Institute, “A Sustainable Water Future for California.” http:// pacinst.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2014/06/ca-water-future.pdf

- U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, “The Wind-Water Nexus,” Wind Powering America Fact Sheet Series. April 2006. http://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy06osti/37790.pdf

- U.S. EPA, State and Local Climate and Energy Program, “Energy Efficiency in Water and Wastewater Facilities.” 2013.

- WRI, “Natural Infrastructure for Water.” 10/13. www.wri.org/our-work/project/natural-infrastructure-water