Composting rule revision, utilization of compost by the Maryland State Highway Administration and consideration of food waste disposal ban are among recent developments.

Lori Scozzafava

BioCycle June 2015

The Maryland Department of the Environment notes that the recycling rate for yard trimmings was 70.9 percent in 2012, while the recycling rate for food waste was about 8.5 percent. Veteran Compost (facility above) in Aberdeen, Maryland composts food waste with ground wood.

Since the early 1990s, the State of Maryland has had active recycling programs and policies. Legislation created recycling goals that challenged Maryland’s 23 counties and the City of Baltimore to recycle. They responded by establishing programs that recovered a wide variety of materials and educating their citizens about how and why they should participate.

The progress of these programs has been tracked by the Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE) in the form of an annual survey of its counties. A report is then developed which documents the state’s total recycling tonnage (generated from residential and commercial sources.) Maryland’s latest annual recycling report boasts a 44.5 percent recycling rate for 2013 (MDE, 2014). Almost one third of the 2,797,906 tons recycled that year were organic materials that had been composted.

In 1992, a Maryland law prohibited disposal of separately collected loads of yard trimmings. Therefore, composting of this material has become prevalent in the state. MDE’s “Facts About: Composting in Maryland” states that the recycling rate for yard trimmings was 70.9 percent in 2012 while food waste only had a recycling rate of 8.5 percent (MDE, 2014). Other organic materials recycled included animal bedding, carcasses, silage, wood, grain, yeast, bark and renderings.

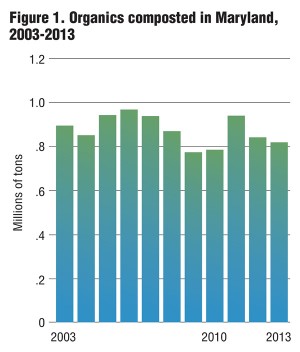

For over a decade, about 800,000 tons of compostable materials (Figure 1) have been reported as recycled, annually (about 10% of the generated waste stream.) However, this underestimates the total amount of organics recycled because of strong backyard composting initiatives in Maryland that are not reported in the total diverted.

The implications of these statistics are both encouraging and challenging. They indicate that infrastructure is in place to handle this amount of organic material. But, there has been little or no growth in the quantity diverted for a long period of time. Additionally, it represents only about one-third of the 28 percent of what the USEPA’s MSW Facts and Figures 2012 Factsheet reports as typical of the organic waste stream generated in the U.S. (USEPA, 2013). Even when the grasscycling and home composting programs of 10 counties are taken into account, it’s possible that Maryland still has about 2 million tons of organic materials being disposed on an annual basis.

Expanding Organics Recycling

The need to specifically push for more recycling of organic materials emerged in Maryland around 2010. Since then, several initiatives may help the state move more aggressively into organics recycling. According to Gemma Evans, President of the Maryland Recycling Network, “throughout Maryland there is a lot of interest in, and conversations about, the possibilities and opportunities presented by organics recycling. We have successful yard trimmings composting and mulching programs, but there is still so much that should be done to divert pre and postconsumer food scraps from landfilling and incineration.” Initiatives to move organics recycling forward in Maryland are described below.

Composting Workgroup

In May 2011, MD House Bill 817 was signed into law. This legislation directed the MDE to study composting in the state and make recommendations to the legislature on how to promote organics recycling. A Composting Workgroup was convened and by December 2012 a final report was created. It contained 15 recommendations that, according to the executive summary, are intended to “reduce barriers to responsible composting” (Land Publications, MDE). They include recommendations for legislative and regulatory initiatives, a call for development of best management practice standards and compost use guidelines, funding for compost education and specific program requests from state agencies that could promote compost use and infrastructure development (including MDE, State Highway Administration (SHA), the Department of Business and Economic Development, the Maryland Environmental Service and the Maryland Department of Agriculture).

Recycling Goals

In 2012, HB 929 — which raised the state’s recycling goals to 35 percent (up from 20%) for counties with a population over 150,000, and 20 percent (up from 15%) for smaller ones — was signed into law. This meant that jurisdictions had to expand their recycling programs and therefore, indirectly, put pressure on them to increase recycling of their organics (given the tonnages of organics still in the waste stream being disposed.)

Composting Facility Regulations

The first recommendation of the Composting Workgroup was taken up by the Maryland General Assembly during the 2012 legislative session. A bill authorized MDE to adopt regulations that govern the design and operations of composting facilities. This was signed into law. MDE then fulfilled another Workgroup recommendation by developing these regulations using model rules, created by the US Composting Council (USCC), as a template. A working group of public and private stakeholders was formed to provide input and guidance. The regulations introduce a new chapter into the MD Code of Regulations (COMAR) as 26.11.04 (Proposed Land Regulations, MDE). Under these rules, different specifications apply to facilities depending on the size of the operation and the type of material accepted. Drafts of these regulations were released by MDE for public comment in 2013 and 2014. The final version has not yet been published but the current version may be downloaded from MDE’s website (link in MDE reference below and in online version of this article).

State Highway Administration Initiatives

Another implemented recommendation of the Composting Workgroup was that the SHA should encourage use of compost and compost products (berms, filter socks and blankets) in its roadway projects. In 2014, HB 878 was signed into Maryland law, which required that the SHA promote use of compost for landscaping, and update its specifications for acquiring and use of compost in erosion and sediment control and storm water management. “Passage of that bill assures the long term demand for finished compost products,” said Michael Toole, spokesman for the USCC’s Maryland-District of Columbia (MD-DC) Committee. SHA was also directed to report, by December 2015 (and each year thereafter), on the amount of compost it uses, and to make recommendations on how the SHA can maximize its use of compost in its projects.

The SHA has begun to meet its obligations under this law. “The Department is taking a multipronged approach in the way we are moving forward, not just meeting the requirements of the law but hoping to exceed them,” explains Sonal Sanghavi, SHA’s Director of Environmental Design. Her department has been working through SHA’s long-standing Recycling Materials Task Force to help demystify compost. She also assembled a work group of SHA employees and assigned four specific tasks to address: A survey of existing practices; development of specifications; creation of a compost tracking system; and compost research. The following describes the progress made in each area:

Survey: A SHA survey was sent out to agencies in other states that oversee road projects. The objective is to learn how they are using compost in landscaping and storm water management. SHA received 33 responses and the compiled results should be completed by the end of this summer.

Specifications: Some portions of SHA’s specifications for the purchase and use of compost and compost-based products for soil erosion and sediment control were updated and posted on SHA’s website. In October 2014, SHA added compost language specific to filter logs (308.03.46) and filter berms (308.03.45) using Type B Compost and included reference to compost in Soil Amendment and Fertilizer (316.03.04). In February 2015, revisions were made to Section 701 (Subsoil and Topsoil), Section 705 (Turfgrass Establishment), Section 706 (Shrub Seeding Establishment), Section 707 (Meadow Establishment) and Section 708 (Turfgrass Sod) to specify Compost (920.02.05) at rates determined in project specific Nutrient Management Plans. The accompanying sidebar shows SHA’s specification for compost that was included in its February 15, 2015 revision. All these revisions can only be found by searching SHA’s webpage for Supplemental Specifications and Provisions to the July 2008 Book. Draft specifications have been developed for berms, socks and blankets. SHA has sent them to MDE for review and approval before they will be officially accepted by SHA.

Tracking Mechanism: Currently, SHA is not tracking the amount of compost it is using annually. However, projects that have nutrient management plans have supplied SHA with some of this information and a baseline tonnage figure will be determined from reviewing current documents. This baseline will be included in SHA’s December report. It has yet to be determined how the Administration will request this information from its contractors in the future.

Research: Concerns within SHA were raised regarding whether leaching from compost may contribute undesirable elements to water bodies that may impact SHA’s ability to meet storm water standards. The Administration contracted with the University of Maryland to determine how compost and compost products perform under conditions found in Maryland. The results from this study are expected in Summer 2015. Additionally, SHA plans to have research contracted for and conducted that will evaluate compost and its contribution to establishment of vegetation. It’s hoped that this research may begin in Fall 2015.

Commercial Food Scraps Disposal Ban

While Maryland was wrestling with how to advance organics recycling in the state, Massachusetts, Vermont, Connecticut, Rhodes Island and New York City had all established policies targeting separation of food scraps for recycling from large-scale commercial operations. With the path laid by these examples, a group of compost supporters in Maryland, including the USSC’s MD-DC Committee, the American Biogas Council and the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, worked with Maryland Representative Shane Robinson to propose a bill during the 2014 legislative session. HB 1081, titled “Composting and Anaerobic Digestion Facilities – Yard Waste and Food Residuals,” has three main components, according to a factsheet developed by this group:

1) Expand the state’s existing disposal ban on source separated yard trimmings by requiring all yard trimmings to be source separated for recycling if a composting or anaerobic digestion (AD) facility exists within 30 miles;

2) Require large-scale food waste generators (two tons per week or more) to source separate food residuals if a composting or AD facility exists within 30 miles; and

3) Require the state to establish regulations for AD facilities.

This bill did not get the support of the Maryland Recycling Network, the National Waste and Recycling Association or the Maryland Restaurant Association because of concerns about the practicality of actual implementation of this bill (if it became law) and the economic impacts on businesses. It was never brought to a vote by the Assembly before the session closed.

Representative Robinson introduced a similar bill during the 2015 legislative session. MD House Bill 0603 was similar to HB 1081 in that it established a ban on food scraps from commercial sources producing more than 2 tons/week. But the proximity requirement to composting or AD facilities increased to 40 miles (from 30) for both source separated yard trimmings and food scraps. The yard trimmings component raised strong objections from county governments. Some Maryland counties do not collect yard trimmings from sparsely populated areas and saw the wording in HB 0603 as creating a need for collection programs that would add cost but not an economical quantity of recycling tonnage.

With these objections and calls for more input from stakeholders, the bill was dramatically changed. The title became “Yard Waste and Food Residual Diversion and Infrastructure Task Force” and the focus was to establish this Task Force, and identify its 20 members (including 2 from the General Assembly, 4 state agencies, 7 nonprofits and public and private organics recycling stakeholders). It required 16 very specific tasks for the Task Force to report and set a schedule for this reporting: January 1, 2016 for interim findings and January 1, 2017 for its final report.

HB 0603 was approved by the House and moved to the Senate Education, Health and Environmental Affairs Committee but was never brought to the floor for a vote before the 2015 legislative session ended.

Lori Scozzafava is a resource management executive whose professional positions include Executive Director for the US Composting Council and Deputy Executive Director for SWANA. She can be reached at LScozzafava@gmail.com.