BioCycle speaks with Dana Gunders of NRDC, author of the newly released guide, Waste Free Kitchen Handbook.

Nora Goldstein

BioCycle November 2015

Author Dana Gunders provides 20 recipes to help inspire use of “the random assortment of ingredients in your fridge at the end of the week, or of those avocados or bananas that are a bit past their prime.”

Food waste warriors don’t plot and fight. We pickle and freeze.” So begins the introduction, “Making A Difference,” of the newly released Waste Free Kitchen Handbook by Dana Gunders, staff scientist at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), who leads NRDC’s campaign to reduce the amount of food wasted across the country.

“My journey to become a food waste warrior started at work, where I was researching how to improve farming,” writes Gunders. “My aim was to help farmers use less water, fertilizers and pesticides. But what I found startled me. After all the effort and resources that were being invested to get food to our plates, a huge amount of it was going uneaten! It occurred to me that no matter how organically or sustainably we grow our food, if it doesn’t get eaten, it doesn’t do anyone any good.”

Gunders put the issue of wasted food on the national radar with her 2012 report, “Wasted: How America is Losing Up to 40% of Its Food from Farm to Fork to Landfill.” She illustrates the amount of food wasted with the image of buying five bags of groceries and then dropping two of the bags in the store parking lot and not bothering to pick them up. “Collectively, consumers are responsible for more wasted food than farmers, grocery stores, or any other part of the food supply chain,” notes Gunders. “….In fact, Americans are throwing away an average of $120 each month per household of four in the form of uneaten food.”

The reality that consumers are the largest source of wasted food in the U.S. prompted Gunders to learn more about the causes and what can be done to change their behavior. Her curiosity and research culminated in the writing and publishing of the Waste Free Kitchen Handbook. Speaking with Dana Gunders about the Handbook, BioCycle asked about her “aha” moments when conducting research, and why, from a climate resiliency standpoint, focusing on food, versus, say, renewable energy or water conservation, is an easier conversation starter.

BioCycle: How did you get the idea for the Waste Free Kitchen Handbook?

Gunders: Consumers are such a big part of the problem of food waste and I kept thinking about what information they needed in order to waste less food. In conversations I’ve had over the last three years with individuals about wasting food, I discovered that no one wants to waste food. But it happens in their lives and my life. I kept wondering “Why? What are we missing?” This book turned out to be a huge learning experience, especially because I don’t have any culinary training. With the exception of the introduction, just about everything was new research for me. My goal was to bring together all that I was learning and inspire a new way of thinking about the challenge of wasting food. For example, when are foods no longer safe to eat? It became clear that people don’t necessarily understand when they can get sick from food. But they don’t have to be afraid, e.g., milk is a pretty safe product once people are armed with the right information.

BioCycle: You coin the phrase “Food Waste Warrior” in the book. Is one goal of the book to teach people how to become food waste warriors?

Gunders: I was using that term before I wrote the book. Food waste warriors are a small subset of people who are extremely passionate about this topic. For these types of people, being a food waste warrior is fun and motivating.

But Waste Free Kitchen Handbook is written for a much broader audience. It is information and inspiration to waste less. I want to inspire the every day person who has to put food on the table with tips about food, regardless of their culinary skills. I like to think of the information in the handbook as “news to use.” That is what I hope grabs people the most — to open to a page and go wow, ‘I didn’t know that!’

BioCycle: What was the biggest challenge you faced in writing Waste Free Kitchen Handbook?

Gunders: The hardest part was pulling together the directory at the end, which provides specific information about many of the foods in your kitchen. The directory offers advice on how to store foods, how to freeze them, and how long they stay at their best quality. It quickly became clear that there is no central source to find that information. It was difficult to get to the level of validity and credibility for sources that NRDC wants. In the end, I used a combination of U.S. Department of Agriculture and Food & Drug Administration information where I could find it, and individual trade associations for suggestions on how to store their products.

In some cases, the process was very frustrating, with a lot of ambiguity on shelf life. Take quinoa as an example. The Whole Grains Council website says it is good for four months when it is kept dry, but I store quinoa for much longer than that and it is fine to use. I feel like some of dates in the handbook are very conservative, but I didn’t want to change anything without a reliable source.

BioCycle: Over the course of your research, what were your top “aha” moments?

Gunders: I had a ton of “aha” moments and a lot of fun learning about different foods. For example, when cheese is kept in plastic it can’t breathe and encourages mold. Fine cheese shops tell you to store cheese in waxed paper. Another interesting thing I learned a lot about is that some foods are fresher for a limited amount of time and thus should be kept in the refrigerator — foods that I always thought of as pantry staples.

Walnuts are a case in point. Recently, I went to a walnut farm and was given walnuts to bring home. I put some in the fridge, and some in the pantry. When I did a taste test, I found a big difference and was surprised to learn that the taste of walnuts that I know and love is in fact not the fresh walnut taste, but a more rancid one. Since walnuts are sold at room temperature at the store, you wouldn’t think they would need to be refrigerated. But the fresher flavor is better!

I also had some feeling of disappointment, when I actually learned that some foods need to be thrown, such as soft cheeses with mold. The more I worked on the book, the more I felt like, oh gosh, I hope people can keep in the spirit of keeping food fresh and not letting it get to the point where it isn’t edible. The spirit of Waste Free Kitchen Handbook is more about fresh food and using it than old food and whether or not it can still be eaten — though information on both is provided.

BioCycle: What do you think will most motivate consumers to waste less food, i.e., to change their behavior?

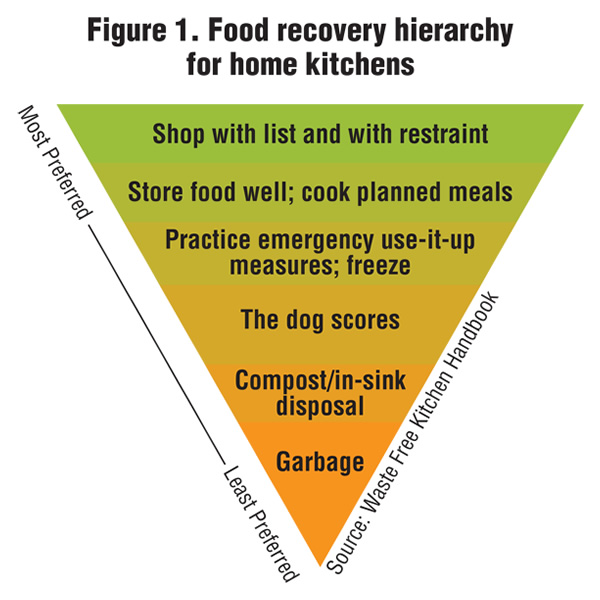

Gunders: One of my main messages is summed up in the beginning of the “Crafty Kitchen” chapter — to approach the kitchen with a “use-it-up” mentality. What I really hope to get across is a different mindset, to encourage consumers to concoct new dishes that make use of whatever ingredients are on hand, to not be afraid to substitute pasta sauce or salsa in a recipe that calls for tomato paste. I created a Food Recovery Hierarchy for Home Kitchens (Figure 1) that I feel sums up what I want to get across with the Handbook. The hierarchy suggests a new mindset about how to manage your food. But I am not sure if that is what will change behavior. Many people are very motivated around the morality of not wasting food. That actually might be what grabs people and changes the way they shop and consume.

Gunders: One of my main messages is summed up in the beginning of the “Crafty Kitchen” chapter — to approach the kitchen with a “use-it-up” mentality. What I really hope to get across is a different mindset, to encourage consumers to concoct new dishes that make use of whatever ingredients are on hand, to not be afraid to substitute pasta sauce or salsa in a recipe that calls for tomato paste. I created a Food Recovery Hierarchy for Home Kitchens (Figure 1) that I feel sums up what I want to get across with the Handbook. The hierarchy suggests a new mindset about how to manage your food. But I am not sure if that is what will change behavior. Many people are very motivated around the morality of not wasting food. That actually might be what grabs people and changes the way they shop and consume.

BioCycle: How much time do consumers need to invest in making these changes?

Gunders: Some aspects don’t require any additional time and effort, e.g., simply better understanding date labels on food products can be helpful to wasting less without costing any time. Or seeing what you have in the refrigerator before you go to the grocery store so you use up what is there first. I think of this as the first wedge of food that can be saved with very little effort. It’s more about gaining knowledge and not requiring a lot of time or energy.

But the next wedge takes more time and energy — it’s where wasting food is more convenient than not wasting it, e.g., blanching and freezing vegetables that would otherwise spoil before you can eat them. That does take a little time. In other cases, it may involve a small sacrifice to eat what you have versus what you are in the mood to eat.

BioCycle: One of the more startling facts I read is that Americans waste 50 percent more food today than we did in the 1970s? What changed in those 45 years?

Gunders: Larger portion sizes are one thing to easily point to, but that is just part of it. Consumers are eating out a lot and not necessarily factoring that into their shopping plans. The truth is, I’m not sure what happened in the 1970s. Perhaps there were more single-earner households so someone in most homes had the time for planning, shopping and cooking.

BioCycle: Clearly you make wasting less food fun. Why is this fun, but saving water or conserving energy, which can be equally or possibly more impactful in terms of climate resiliency and sustainability, likely less fun?

Gunders: It’s food! People love food. Wasted food is an issue with tangible, immediate benefits when it’s changed. This is a topic people love and they love for reasons beyond the resource issues around it. Climate, energy and water tend to be more guilt-driven issues, and I’m not sure why. People save energy because they feel guilty so turn lights off. You don’t naturally have the other benefits that come with food. And the solution for the problem of food waste is directly connected to solutions for eating better — you are eating fresher and better quality food. It is a very fortunate overlap.

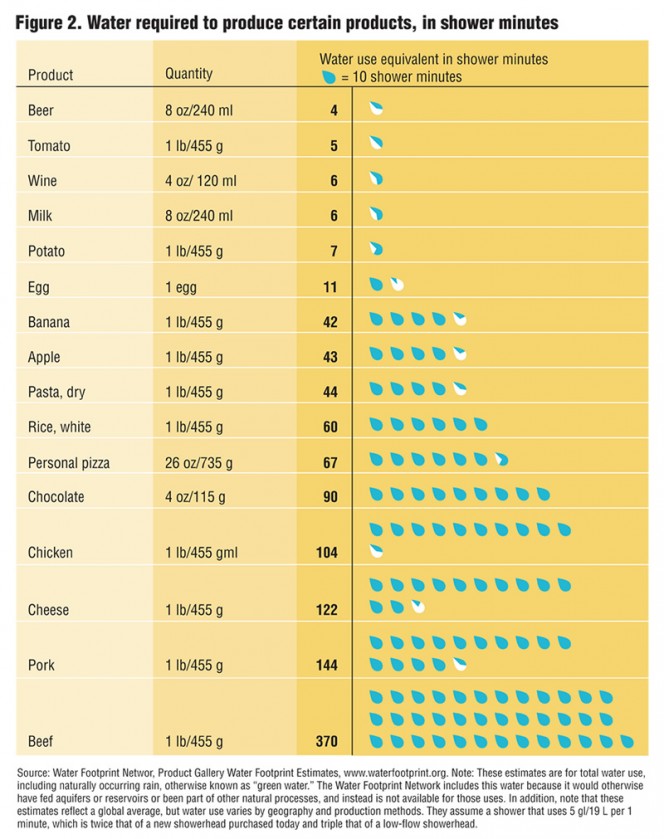

That said, I also believe that raising awareness and changing behavior around wasted food is a gateway to involving all of these people who are not currently speaking with an environmental voice. An example is captured in a table in the Introduction where I calculate “shower minutes” to illustrate water required to produce certain products (Figure 2). The Waste Free Kitchen Handbook introduces consumers to source reduction and composting, as well as growing food. It allows for a lot of creativity — there are so many tips and tricks.

That said, I also believe that raising awareness and changing behavior around wasted food is a gateway to involving all of these people who are not currently speaking with an environmental voice. An example is captured in a table in the Introduction where I calculate “shower minutes” to illustrate water required to produce certain products (Figure 2). The Waste Free Kitchen Handbook introduces consumers to source reduction and composting, as well as growing food. It allows for a lot of creativity — there are so many tips and tricks.

BioCycle: NRDC is working with the Ad Council on a consumer campaign to reduce food waste. What did you learn from writing the Handbook that has helped to inform the Ad Council campaign?

Gunders: There are three reasons to target consumers:

We waste a lot in our homes.

We need to change the consumer mindset in order to give businesses the social license so they can waste less food. For example, less food would be wasted if consumers didn’t expect to get anything and everything immediately up until a store closed. For example, less chicken would be wasted if a store felt that without disappointing their customers, they could say “We don’t cook rotisserie chickens the hour before closing in order to reduce waste, but we’d be happy to make one for you given 10 minutes notice.”

Consumers are people! And those who hear the message may take it into their own spheres of influence, whether they are a teacher, a waitress, or planning a wedding.

BioCycle: BioCycle reports primarily on the recycling of food that gets wasted, in order to produce soil amendments and clean energy that can be used to grow more food. But we also report regularly on source reduction and food rescue, including the tools and tips in publications like yours. What would you like to see the organics recycling community take away from the Waste Free Kitchen Handbook?

Gunders: The book has information that everyone can use, whether in their day jobs or at home. It also is a great complement to any composting or food waste collection program because it focuses on providing information to promote source reduction. My hope is that it can be a resource to inform the groups that BioCycle readers work with, to help reduce waste in their communities.