Sally Brown

BioCycle December 2017

One size does not fit all. This applies to both size and style. Just think back on those sweaters from holidays gone by. In the modern world we have options like eBay and Goodwill to assure that the purple sweater with the sequins from your distant aunt finds someone who will cherish it. The sweater need not languish in your closet.

Historically, the one size fits all paradigm extended past our closets and to our household infrastructure. You had no choice but to sign up for electricity from the local power company, water from the water utility and garbage collection from the local solid waste hauler. Now options for all are starting to show up on the household, neighborhood and municipal level. Solar comes in sizes from small enough to charge your phone to large enough to power a community. We are seeing water systems that go from rain barrels to community cisterns.

Perhaps nowhere is the array of options more apparent than for organics recycling. As states, cities and individuals make the move to go from landfill disposal to recovery of food scraps, an array of options for collection and processing are available. What is the best choice to make sure that those scraps end up in a composting pile and not languish (like the sweater) in a garbage can?

Perhaps nowhere is the array of options more apparent than for organics recycling. As states, cities and individuals make the move to go from landfill disposal to recovery of food scraps, an array of options for collection and processing are available. What is the best choice to make sure that those scraps end up in a composting pile and not languish (like the sweater) in a garbage can?

Select Your Scale

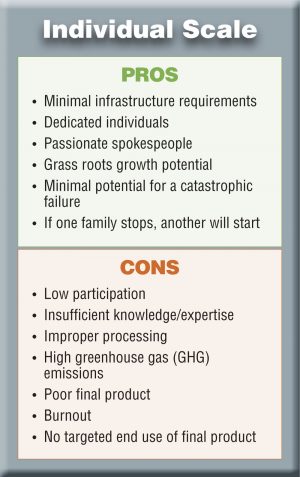

Food scraps collection and composting can and is being done on a household, community and municipal scale. Each of those sizes is a perfect fit for some and a sweater with sequins for others. Each has its associated benefits and risks. On a municipal level, a decision to push for household level composting may sound terrific. You don’t have to think about changing bins or collection trucks. You won’t have to invest the time and aggravation in siting a large-scale facility. You can just create a website and come up with some educational materials. While it is highly unlikely that this approach will lead to widespread diversion, you are likely to get a few very dedicated families or individuals.

Many of these community systems are visible to the community. This is a great tool for communication and for growing the pile. As neighbors walk past and see what is going on, chances are good they will be inspired to bring their own food scraps and potentially even lend a hand. They also will be sensitive to contamination in their scraps, fearing the wrath of neighbors.

If these community piles grow with some help from the municipality in the form of providing land, education, training and even funding or equipment, there is also a good chance that the composting will be done well. On the other hand, if volunteers are working without training, support or appropriate equipment, there is a good chance that the compost and piles will not smell sweet and may in fact change from a neighborhood asset to a neighborhood nuisance. Volunteers may get frustrated and burnt out over time, suggesting that these sites may not be in it for the long haul. So higher visibility means more potential to achieve greater participation and higher levels of diversion. Without adequate support however, the potential for failure increases, as will the repercussions of that failure.

If these community piles grow with some help from the municipality in the form of providing land, education, training and even funding or equipment, there is also a good chance that the composting will be done well. On the other hand, if volunteers are working without training, support or appropriate equipment, there is a good chance that the compost and piles will not smell sweet and may in fact change from a neighborhood asset to a neighborhood nuisance. Volunteers may get frustrated and burnt out over time, suggesting that these sites may not be in it for the long haul. So higher visibility means more potential to achieve greater participation and higher levels of diversion. Without adequate support however, the potential for failure increases, as will the repercussions of that failure.

Amping It Up

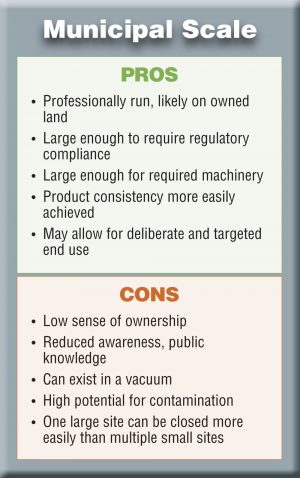

Say you want to go all out. You are ready to invest and have everyone join the party — like a citywide potluck for food scraps. There are many good things about this approach. It has the highest potential of the three size options to be professionally run with appropriate equipment on dedicated land, with regulatory compliance oversight. These things help to ensure that the compost produced is pathogen free and of high quality. It also means that there will be a centralized source of compost for targeted end uses such as storm water infrastructure or other municipal projects.

Sounds great on paper, but what about in practice? There the potential pitfalls can become all too apparent. Your residents may have access to centralized collection but will they participate? It is much harder to build a sense of pride and ownership for compost that is produced somewhere else and may not even be available for citizens to use. That low sense of ownership can lead to both low rates of participation and high rates of contamination — not a good combination. And large sites, even with appropriate equipment and trained employees, can sometimes go sour. The smell associated with a municipal facility makes headlines and can result in lawsuits. In other words, failure on a municipal level can be catastrophic.

Sounds great on paper, but what about in practice? There the potential pitfalls can become all too apparent. Your residents may have access to centralized collection but will they participate? It is much harder to build a sense of pride and ownership for compost that is produced somewhere else and may not even be available for citizens to use. That low sense of ownership can lead to both low rates of participation and high rates of contamination — not a good combination. And large sites, even with appropriate equipment and trained employees, can sometimes go sour. The smell associated with a municipal facility makes headlines and can result in lawsuits. In other words, failure on a municipal level can be catastrophic.

So this holiday season, what is the right approach for getting food scraps to a composting pile in your community? Here it might make sense to think of the diversity of your holiday gift list. That sweater that started off this column would likely make someone very happy. Others will say forget the sequins and bring on the cashmere. There are those who will only wear polar fleece that they can throw in the wash. In other words, there is no single sweater — and by association or use of metaphor — composting system that will be right for everyone in your community. If you really want to maximize the rate of food scraps diversion, your best approach is to go for all sizes rather than one size fits all. This may not be the answer that you want to hear or anything close to a simple approach, but people come in all shapes, colors, sizes and behavior patterns. Luckily so do composting facilities. Happy Holidays!

Sally Brown is a Research Professor at the University of Washington in Seattle and a member of BioCycle’s Editorial Board.