Marsha W. Johnston

BioCycle December 2017

FOG in the sewer systems causes billions of dollars annually in repairs and maintenance to unclog the pipes, and can generate odors.

The traditional model for FOG collection and disposal includes:

1) Sewer utilities engage in individual regulatory transactions with FSEs to ensure compliance.

2) To comply with the utility, restaurants engage in individual retail transactions with waste haulers for grease trap cleaning and maintenance at, and waste removal from, the premise.

3) Haulers responsible for servicing the FSE engage in a transaction (typically paying a tipping fee) to dispose of the grease. In some instances, a wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) is paid to receive the FOG and utilizes it for codigestion.

Example of FOG collection at regulated food service establishment in Tempe by grease hauling service contracted by the City’s cooperative.

Furthermore, due to enforcement responsibility being delegated to the restaurant premises manager and regulatory criteria limited to cleaning practices at the premises, all regulatory control stops at the restaurant’s property line. Beyond that, neither the restaurant nor the utility have any authority over the unregulated transport of FOG. At the same time, adds McNeil, traditional random municipal inspections cannot accurately determine a grease hauler’s performance and compliance unless they occur within a 2- to 3-hour window of the service event, “which is virtually impossible without an army of inspectors.”

Forming A Cooperative

After nearly four years of successfully operating a voluntary retailers’ cooperative for collecting FOG from city restaurants — known as the Tempe Grease Cooperative (TGC) — the City believes it has the answer to maintaining service and feedstock quality control throughout the FOG supply chain. Retailers’ cooperatives have long been used by groups of independent retailers to leverage their collective purchasing power to obtain competitive advantages in the marketplace by acquiring discounts from suppliers and sharing marketing costs through a central buying organization. Examples include True Value and Ace Hardware, Best Western Hotels and NAPA Auto Parts.

Although TGC developers had never heard of a retailers’ cooperative implemented by a local government, they realized that the business model would provide the piece missing from the traditional FOG collection model: utility ownership of FOG waste/feedstock. Thus, in 2012, the Tempe City Council passed an ordinance granting the city authority to engage in procurement of grease recovery services on behalf of its restaurants, followed by a resolution in 2013 establishing TGC’s terms and structure. Now the City of Tempe brokers both pricing and service quality for grease hauling services on behalf of regulated restaurants that voluntarily enroll in the TGC.

“We take over compliance of grease disposal from restaurants,” says McNeil, who is quick to point out that the city does not force any restaurants into the program. “We say, ‘Look, you have to comply with the regulatory agency, but click here and we will comply for you. You won’t be responsible for it, we will make sure your plumbing is taken care of, odor problems, everything.’ And they say, ‘So the choice is either I have to do it and be responsible for noncompliance of the hauler, or letting you do it? How much is it going to cost me?’ And we say ‘20 percent less because we are buying in bulk.’” He adds that the cost is less for its partner haulers too, as it sharply reduces their marketing and billing costs.

As the central buying organization, the utility provides member restaurants with both service discounts and compliance assurance under its collective contracts. Unlike traditional FOG regulation, transaction management allows the City to manage grease hauling services beyond the property boundary of the regulated business. In addition to GPS and other tracking requirements to ensure complete transparency in the transport and disposition stages of service, contracts with haulers establish city ownership of hauled waste, securing its availability and manageability as codigestion feedstock.

“At the BioCycle REFOR17 Conference in Portland in October, I heard investors in anaerobic digester projects repeatedly say that feedstock security and consistency is one of the primary problems they have to resolve,” notes McNeil. “And then we thought, ‘we are trying to fine-tune an instrument from a waste management standpoint, and you guys are trying to fine-tune it from a feedstock security standpoint, but our solution provides both! The city controls the entire disposition, and we know the makeup of each load because we know which restaurants it came from. We heard over and over about the uncertainty of feedstock security, and I’m thinking, ‘We have solved that by securing feedstock without the tipping transaction and by collecting at the restaurant’.”

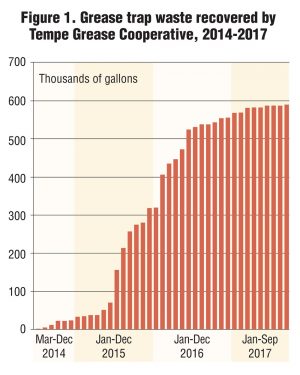

Since TGC launched in March 2014, 182 food service establishments, or over one in six regulated food businesses in Tempe, have enrolled, securing almost 600,000 gallons of total grease trap waste annually — compared to virtually zero when the co-op began (Figure 1). Two of the city’s three school districts, city facilities, hotels, and Arizona State University, the largest public university in the country, are customers.

Since TGC launched in March 2014, 182 food service establishments, or over one in six regulated food businesses in Tempe, have enrolled, securing almost 600,000 gallons of total grease trap waste annually — compared to virtually zero when the co-op began (Figure 1). Two of the city’s three school districts, city facilities, hotels, and Arizona State University, the largest public university in the country, are customers.

The net effect is that partners in the TGC collectively are keeping tons of grease out of the sewer and creating a more livable city by reducing odors from the sewers community-wide, all at a lower cost for both the utility and its regulated users. McNeil acknowledges that some grease haulers might believe the city is creating an unfair advantage by entering the marketplace. “TGC supports business for haulers who are on the up and up, providing good service at a competitive price,” he explains. “It disadvantages haulers who provide bad service.” Furthermore, the co-op model, with its end-to-end contracts, creates “investment grade hauling” for mom and pop companies using municipal stability typically found only in national companies, he adds. “Everybody wins.”

Codigestion Opportunity

With cheap energy rates due to lots of hydropower and low tipping fees at landfills, Arizona has no mandates for organics diversion and few incentives for renewable energy generation. Consequently, no wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) are capturing and utilizing biogas in Arizona. Largely due to that environment, and because Tempe does not own or operate its own WWTP, TGC’s FOG is being dewatered and landfilled, while fryer grease is converted to biodiesel by the City’s yellow grease vendor.

However, through a public-private partnership with Ameresco, the 91st Avenue Wastewater Treatment Plant in Phoenix, expects to begin capturing the biogas from the plant’s anaerobic digesters shortly. Codigestion could follow in the future. The WWTP is owned by a Sub-Regional Operating Group (SROG) comprised of Phoenix, Glendale, Mesa, Scottsdale, and Tempe, and is operated by the City of Phoenix.

Ameresco will design, build, own, operate and maintain (DBOOM) the innovative wastewater biogas-to-energy facility. McNeil says Ameresco already has buyers for the renewable natural gas (RNG) in California, and expects to start sending the RNG to California via natural gas pipeline in the first or second quarter of 2018.

The Ameresco partnership is not yet adding FOG to the process. But McNeil notes that one of the initiatives in TGC’s recently launched 5-Year Strategic Plan (2018-2023) is to approach the 91st Avenue WWTP co-owner partner cities (Phoenix, Tempe, Mesa, Scottsdale and Glendale) to solicit interest in FOG codigestion and expand the co-op as the regional program for its feedstock sourcing.

The plan also has a goal of 100 percent FOG codigestion. To do that locally, TGC will have to work out a public-private partnership to build a digester or to partner with other utilities to build one. Regionally, the TGC could partner with neighbor utilities to utilize excess capacity in existing WWTP digesters, like 91st Avenue WWTP and others. “We are getting interest from renewable energy companies regarding siting AD facilities (food/FOG) near Tempe and using the Co-op to get a commitment for feedstock,” he explains.

Other elements in the TGC’s strategic initiative include developing software to facilitate the co-op’s administration, and to partner with other utilities and research organizations to study the economic benefits of innovative supply-chain solutions to some of the obstacles to FOG codigestion. TGC has contracted with a third-party software provider specialized in FOG waste management for a package that enables utilities to manage FOG pretreatment programs.

As for studies, McNeil says TGC wants to do a triple bottom line compliance study, and quantify a number of values related to compliance assurance. Those values include how much the removal of 600,000 gallons of FOG from sewers is contributing to maintenance cost reduction and the specific value of a consistently clean, high-quality feedstock. “With regard to sewer clogging, we certainly have seen a reduction in odors in our downtown area, but have not quantified that reduction yet,” he notes. On deck for TGC next year, McNeil adds, is to deploy a pilot program to enlist some of its members in food waste collection, and to provide potential TGC members a discount on city commercial solid waste service if they sign up for the co-op.

Marsha W. Johnston is a Contributing Editor to BioCycle and an Editor at Earth Steward Associates in Arlington, Virginia.