Could this state serve as a national model for how to catalyze the biogas economy?

Nora Goldstein

BioCycle September 2018

A recent BioCycle article, “Swine Manure To Biomethane”, reported that 9 million hogs live on 2,217 farms in several counties in eastern North Carolina. If all of the swine manure from those operations were anaerobically digested, the energy value of the biogas would be greater than the total energy consumed by 70,000 households, noted the article. That biogas, when combined with other potential sources — from landfills, wastewater treatment facilities (WWTFs), poultry farms and dairy operations — puts North Carolina third in the U.S. (after California and Texas) in terms of available biogas resources, according to an assessment by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

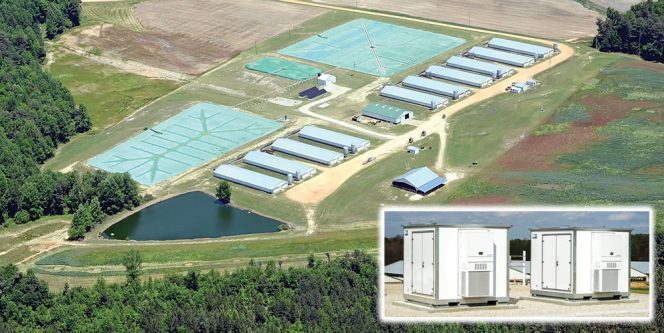

Biogas upgraded at Optima KV is cleaned and pressurized to be sold to Piedmont Natural Gas. The Optima KV project collects biogas from five digesters processing manure from 60,000 hogs. Photo courtesy of Cavanaugh

A May 2018 draft report released by the North Carolina Energy Policy Council noted that the state has over 940 permitted municipal WWTFs, 35 of which are considered major facilities (defined as a design influent flow of greater than 10 million gallons/day). In total, 42 WWTFs in North Carolina utilize anaerobic digestion in their treatment works. Of those, only about 20 have biogas harvesting systems coupled with anaerobic digesters. In addition to the more than 2,200 swine farms, the state is home to approximately 160 dairy farms, and an estimated 5,700 poultry farms, stated the report.

The state of North Carolina has all the ingredients to move the biogas needle — organic waste that needs alternative management solutions, a Renewable Energy Portfolio Standard with a carve-out for swine waste-derived energy, and pioneering projects that are paving the way for those to follow. This article discusses the various elements that are aligning to advance biogas production and use. The information is based on conversations with a wide range of bioenergy stakeholders in North Carolina, as well as public documents and newspaper articles.

Historical Context

The traditional manure management method for hog growers in North Carolina is a combination of open-air storage lagoons and sprayfields. These systems are regulated by the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (NCDEQ), and require permits issued by NCDEQ to operate. Over the decades, this traditional method of swine manure management has raised various environmental and public nuisance concerns.

In July 2000, then North Carolina Attorney General Mike Easley announced a major agreement between his office and Smithfield Foods, Inc. (now the world’s largest hog producer and pork processor) to identify alternatives to open air hog lagoons and sprayfields in the state. Smithfield Foods provided $15 million to the effort to identify alternative waste management technologies, which was increased to $18 million through contributions from other swine industry interests. North Carolina State University (NCSU) was appointed by the state to identify and evaluate new technologies intended to replace the lagoons. Titled “Environmentally Superior Technologies (EST),” these hog waste management alternatives were to be implemented on North Carolina hog farms if they were proven to be effective at meeting the environmental performance criteria and determined to be “operationally and economically feasible as well as permittable by the appropriate regulatory agency.” (See “Advances In Swine Manure Management,” October 2005, for specifics.)

The Animal and Poultry Waste Management Center (APWMC) at NCSU was given the central role of coordinating development and implementation. The EST had to meet five technical performance standards. Ultimately 18 technology candidates were selected and evaluated; however, none were determined to meet the criteria set forth for performance and economic feasibility. Some of the systems evaluated included anaerobic digestion (AD), but AD, alone, was not found to meet all the environmental performance criteria, though its ability to produce value-added products, such as biogas, showed promise of satisfying the economic feasibility.

In 2007, given public health and environmental concerns related to the open-air lagoons and sprayfields, the North Carolina legislature passed a permanent ban on the construction or expansion of lagoon and sprayfield systems, and established stringent health and environmental standards for all new farms or farms that wished to expand. Existing open-air lagoons and sprayfields, however, were grandfathered in.

Renewable Energy Portfolio Standard

Much of the current biogas-related focus in North Carolina centers around pipeline injection of renewable natural gas (RNG) and how the RNG can help regulated utilities in the state comply with the swine-to-biogas requirement in the Renewable Energy Portfolio Standard (REPS). That injection opportunity, combined with millions of tons of swine and poultry manure, is leading to development of new AD infrastructure. The REPS became law in 2007 and requires utilities to generate up to 12.5 percent of their energy needs through renewable energy resources and energy efficiency programs by the end of 2020. These utilities are also required to use hog and poultry wastes to generate a portion of their renewable energy requirements. The carve-out for swine waste-derived energy is 0.2 percent (of the 12.5%) by 2019, up from 0.07 percent in 2017.

Compliance with that requirement keeps getting pushed back as each year since its adoption, the obligated utilities request an off-ramp from the schedule citing lack of viable projects that allow for compliance with the requirement. It has been voiced by many close to the issues in North Carolina Utilities Commission (NCUC)-mandated stakeholder meetings that lack of infrastructure to get manure-generated biogas into the grid as electricity or into the natural gas pipeline as RNG are obstacles to a faster project development pace.

Duke University and Duke Energy, and later Google, developed and funded an AD system at Loyd Ray Farms, a swine finishing operation. The facility began operating in 2011. Photo courtesy of Duke University Office of Sustainability

The Players

Today, there are about 20 anaerobic digesters on about 10 swine and poultry farms in the state. Most of the 8.7 million tons of swine manure produced annually continues to be managed through open-air lagoons and sprayfields. Two of the farm-based AD facilities receive food waste for codigestion. There is one stand-alone commercial digester in the state that receives primarily food waste. Located in Charlotte, the Orbit Energy Charlotte facility is sized to produce 5.2 MW of energy. (North Carolina also has 7 permitted composting facilities that process food waste.)

A number of entities are working independently, as well as collectively, to accelerate development of AD infrastructure in North Carolina. These include state agencies, academic institutions, trade groups and AD facility developers and consultants. The following describes some of these entities:

• North Carolina Energy Policy Council (EPC): The EPC, an independent body staffed by the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (NCDEQ), advises the Governor and General Assembly on legislation and rulemaking that addresses domestic energy exploration, and encourages economic development. EPC members have expertise in areas such as research and policy, environmental management, the utility industry and energy resources. In its 2016 report, bioenergy was briefly referenced. However, due to interest among some members of the EPC, bioenergy was addressed in more detail in the May 2018 draft report, including specific recommendations. One is a bioenergy resource inventory and economic impact analysis being carried out by Duke University. The analysis is exploring current biogas production potential from North Carolina’s hog and poultry waste, and how much is technically recoverable given highest and best end uses and geographical considerations. (Duke Energy, via an R&D fund for REPS implementation, has budgeted $250,000 each year for two years for the inventory.) Others are to establish goals for the capture and refining of biogas into RNG for distribution, and incorporation of biogas-derived natural gas into the state’s transportation fuels program for its fleets and public transportation.

• State Agencies: NCDEQ has rules that apply to the design and permitting of AD systems for all types of organics. These were used to permit existing digesters in the state. NCDEQ’s Division of Water Resources (DWR) regulates animal feeding operations (AFOs), including livestock manure. The Division of Air Quality regulates emissions from the combustion or processing of biogas into electricity, RNG, or any other value-added product. The Division of Waste Management (DWM) regulates landfills, transfer stations and composting facilities. It permitted the Orbit Energy digester in Charlotte because the feedstocks are primarily from the solid waste stream.

The North Carolina Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services’ (NCDACS) Division of Soil and Water Conservation is involved with farm nutrient management plans. The Veterinary Division regulates livestock mortality management. And the AgriBusiness Development office gets involved with value-added agricultural products, including bioenergy. NCDACS created a New Market Initiative several years ago to explore new agricultural markets for the state’s farmers, which includes biogas.

The Bioenergy Research Initiative (BRI), which is within NCDACS, provides grants to explore topics ranging from growing energy crops for cellulosic energy production to renewable heating of small greenhouse production facilities. An energy crop initiative started in 2011, the “Sprayfield Project,” was established on three hog lagoon sprayfields in three counties At that time there was hope for a cellulosic ethanol plant to be built in that area, noted the BRI. Researchers planted switchgrass and Giant Miscanthus (perennials) and biomass sorghum (an annual) to compare with Coastal Bermuda (the typical perennial used on sprayfields). NCSU continues to evaluate nutrient uptake by the crops as well as yields.

• NCSEA Biogas Working Group: The North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association (NCSEA) formed a Biogas Working Group in late 2016 to expand markets for biogas and provide economic benefits to the state. Among its first tasks was to work with Piedmont Natural Gas on an RNG standard for pipeline injection. Piedmont filed its standard with the North Carolina Utilities Commission (NCUC) in 2017.

• Universities: As noted, NCSU has been very involved in the EST research over the years; one current area of research is nutrient management technologies and systems. Duke University has taken a leading role in biogas-related research and analysis, as well as facility development. In 2008, Duke University and Duke Energy (later joined by Google) teamed up to develop and fund an anaerobic digestion-based system that meets all of the environmental performance standards at Loyd Ray Farms in Yadkin County, a swine finishing facility with nearly 9,000 pigs at any given time. The system began operating in May 2011. Duke University and Google receive the carbon offsets, and the University has access to the facility for research and education purposes. Duke Energy receives the renewable energy certificates generated by making electricity on-site from the biogas. In 2013, the Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions at Duke University produced a statewide analysis of swine waste-to-energy production options, identifying use of biogas as the most cost-effective approach for compliance with the state REPS.

• North Carolina Biotechnology Center: The Center is an economic development group that focuses on biotechnology, including agribusiness. One of its focus areas is fuel and energy, which has led to NCBC’s interest in anaerobic digestion and biogas.

• Utilities, Utility Commission: In 2012, a NCUC ruling recognized directed biogas as a legitimate fuel for renewable energy credits. (Directed biogas is injection of RNG into a natural gas pipeline with an equivalent amount of natural gas (not necessarily the RNG) taken out of the pipeline to power a combined cycle natural gas plant, the electricity generated from which is eligible for a renewable energy certificate.) Duke Energy is the dominant utility in North Carolina. Its subsidiary, Piedmont Natural Gas, is the receiver of the directed biogas injected in the pipeline from the Optima KV AD project.

Recently, an electric cooperative in the state, part of NC Electric Cooperatives, initiated a microgrid pilot project with Butler Farms, a hog producer with an anaerobic digester and other innovative waste management practices. The goal is to improve the reliability of the electric system and farm operations by avoiding prolonged outages after storms or other events that interrupt grid power. The microgrid components include 20 kW solar panels, a 100-kW diesel generator, a 185-kW biogas generator, a 250 kW/735 kWh battery system, and a controller.

State Of Play

In mid-May, the NC Energy Policy Council focused its quarterly meeting on bioenergy, with speakers addressing resources, perspectives, opportunities and impacts. The presentations captured the State of Play in North Carolina with regard to biogas generated by anaerobic digestion. Here’s a sampling:

• Tanja Vujic, Duke University: The pluses include a significant supply of organics to generate biogas via AD; the REPS carve-out for swine and poultry waste-to-energy; revenue streams from sale of RNG via the Renewable Fuel Standard and California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard; and nuisance lawsuit rulings providing a window for change.

The negatives, however, are significant, including a lack of infrastructure to transport gas and a lack of priority for enabling directed biogas on the part of local gas distribution companies; ease of utility noncompliance with REPS; cost to connect and inject biogas; price of conventional natural gas; and overall fatigue with the swine waste issue. Vujic’s last slide suggests creating one entity capable of actively coordinating biogas development to achieve maximum benefit for all stakeholders and to bring private and public resources to bear where gaps remain.

• Randall Johnson, NCBC: Economic opportunities related to biogas include “catalyst for new investment” in North Carolina’s agricultural sector, which represents the largest portion of the state’s GDP. Also will provide “optimization of existing, underutilized assets” and “access to new and emerging markets.”

• Kraig Westerbeek, Smithfield Renewables: Company has a belief that farmer-owned digesters/covers and gas aggregation “may be the best option for North Carolina (NC) farmers”; and stated goal of “82 percent [hog] finishing capacity in NC participating in RNG production — approximately 5 million MMBTU opportunity.” In addition to providing funds for the EST research described above, Smithfield has invested millions of dollars in researching waste treatment and biogas systems across the country.

• Joe Rudek, Environmental Defense Fund: Noted that “anaerobic digesters are not designed to solve all swine farm environmental and public health risk issues.” He identified supplemental measures that could improve upon AD to get farms closer to the environmental performance standards put in place for all new and expanding farms but not required for existing farms.

• Jamie Cole, North Carolina Conservation Network: Stated that “directed biogas projects are not EST [Environmentally Superior Technologies]” and that while covering lagoons for methane capture “does assist with odor control and reduces release of methane into the environment,” there is still release of atmospheric emissions of ammonia and continued emission of noxious odors from the hog barns and composting.

A microgrid pilot project was installed at Butler Farms, a hog producer with an anaerobic digester. Components include a battery system and controller (below), solar panels, a diesel generator and a biogas-powered generator. Photos courtesy of Butler Farms

Latest Developments

The biogas landscape in North Carolina could be impacted by several factors. Federal juries in three nuisance lawsuits filed against Murphy Brown, LLC, a subsidiary of Smithfield Foods, ruled in favor of the plaintiffs this year, according to an article in the Raleigh News and Observer (“Jury awards hog farm neighbors their biggest verdict yet,” Aug. 3, 2018). Improved manure management practices will be necessary, and AD is a vehicle to generate revenues that could offset capital costs. Among research initiatives targeted at AD technologies is a study being launched by NCSU to potentially reduce the size of covered lagoon AD systems. It is testing manure scraper systems versus the current practice of flushing the barns to remove manure.

On the biogas markets side, in late 2016, Duke University began a formal assessment to determine if a sufficient supply of biogas could be secured in North Carolina to reduce the need for fossil fuels on campus and support the University’s commitment to climate neutrality by 2024. This past a spring, after delaying plans to construct a combined heat and power (CHP) plant on campus, Duke committed to displacing conventional natural gas — the primary fuel source for the current steam plants on campus — with directed biogas (RNG) from swine farms in the state.

Duke University’s demand for RNG, and the swine waste-to-energy carve-out in the REPS, have encouraged private sector development of AD infrastructure to produce RNG in North Carolina. This demand also has prompted a push to standardize RNG injection rules to streamline the RNG injection process. However, the NC Utilities Commission (NCUC) issued a surprise ruling on June 19, 2018 regarding approval of Piedmont Natural Gas’ (PNG) regulations governing injection of “alternative” gas [RNG]. Rather than standardizing injection rules for market participants, the NCUC announced a three-year pilot program for RNG injection that would restrict access to projects that offered new data. According to the NCUC, it “would be premature to approve unconditionally Piedmont’s Appendix F [injection specifications], in light of the Commission’s ongoing concerns related to potential service quality and operational issues.” The NCUC made this ruling despite stakeholder agreement that concerns raised by the Commission could be effectually mitigated through a testing regimen.

Regarding the pilot program, the Commission declared that the two projects it approved — Optima KV and a large-scale AD facility under development (C2e Renewables NC) — qualified for inclusion and that others would be allowed to participate in the pilot program provided developers “demonstrate … that such additions … will be useful in gathering the information and data sought by the Commission.” Essentially, the NCUC wants PNG to gain experience with the receipt of RNG from the approved projects.

The North Carolina Pork Council filed a motion in early August asking the Commission to reconsider its order. All motions had to be filed by August 20, 2018.

The Road Ahead

Despite the wrench thrown into the mix by NCUC in June, there nevertheless is forward momentum in North Carolina to catalyze the biogas economy. Unlike other states where BioCycle REFOR has been held in recent years — including California — solutions have to be implemented much sooner than later to meet growing demand, address environmental and nuisance concerns and capture economic opportunities.