Nora Goldstein

The Biodegradable Products Institute (BPI), North America’s leading certifier of compostable products and packaging, released a first-of-its-kind set of labeling and identification guidelines designed to support organics diversion and reduce contamination for composters. The 26-page Guidelines for the Labeling and Identification of Compostable Products and Packaging features category and material-specific recommendations to make it easier for consumers and composters — as well as the food establishments utilizing the products — to distinguish between compostable and non-compostable items.

“Compostable products and packaging exist to help facilitate the diversion of food scraps from landfills,” explains Rhodes Yepsen, Executive Director of BPI. “Unfortunately, the threat of contamination from ‘look alike’ non-compostable packaging has led some composters to discontinue accepting even certified compostable items. The first step to managing this contamination is through consistent labeling. These new guidelines set the standard for designing products that are readily and easily identifiable as compostable. A consistent identification strategy employed by product manufacturers and brand owners is a key driver in achieving differentiation and will assist in the acceptance of food scraps and compostable products and packaging on a larger scale.”

BPI describes these guidelines as “the first iteration of an ongoing collaborative effort between composters, governments, brand owners, and the compostable products industry.” Key stakeholders provided feedback during their development, including the US Composting Council (and its state chapters), the California Compost Coalition, the Compost Manufacturing Alliance, independent composters, the City of Seattle, Zero Waste Washington, the Foodservice Packaging Institute, Sustainable Packaging Coalition, foodservice operators and brand owners. BPI expects the document to be dynamic, and encourages composters and other stakeholders to provide feedback. The guidelines also note that state and local governments can use the document to inform their conversations around labeling and identification requirements for compostable products and packaging, particularly as it relates to product and category-specific manufacturing capabilities that vary with factors like shape, size, and material type.

In the Guidelines, BPI distinguishes between “end users” and “consumers.” Notes BPI: End user would be a foodservice customer (like a coffee shop or restaurant patron) and consumer would be an actual retail purchaser (someone buying compostable coffee pods on retail shelves).

Factors To Consider

To facilitate understanding of BPI’s recommendations for the labeling and identification of compostable products and packaging displayed in Part Two of the guidelines, Part One reviews the variety of considerations that “should be taken into account when determining how to properly label and identify compostable products and packaging.” These include:

- Legal & Regulatory Requirements: Compostable products and packaging are subject to specific labeling requirements — primarily as they relate to claims about compostability and access to composting facilities. These have been established by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) in the U.S., the Competition Bureau (CB) in Canada and various state/provincial and local governments across both countries — and have been on the compostable packaging’s playing field for a number of years. BPI has its own labeling requirement: All products it certifies as compostable must include the BPI Certification Mark.

- Technical Considerations: Currently, manufacturers of compostable products and packaging have 3 primary techniques for labeling and identification:

- Printing: “Printing is a reliable method of delivering specific information on a product or package, whether through visual elements like a stripe, or with words and symbols,” notes BPI. The caveat is that “printing may not be possible — or may be a significant challenge — on many of the products covered by these guidelines.” For example, printing on certified compostable clamshell packaging will require advancements in technology.

- Material coloring and tinting: These achieve “visual differentiation,” says BPI, “however, are not sufficient on their own to clearly identify compostable products and packaging.” For example, there is no “universal” color or tint that is used exclusively on compostable products and packaging, thus coloring and tinting doesn’t address the potential for conventional plastic look-alikes.

- Embossing, debossing or otherwise etching: These techniques “may make it possible to deliver the information required,” explains BPI. “This messaging strategy is most effective when the wording is prominently featured on the products and packaging and is legible by consumers and composters.”

- Space: Lack of space is often cited by manufacturers and brand owners as a challenge when considering language and logo usage on compostable products and packaging. Some of the spatial challenges are due to existing regulatory requirements for labeling and compostability claims.

- Composter, Brand Owner, Consumer and End User Considerations: In a nutshell, composters need compostable products and packaging that are readily and easily identifiable — including from afar (e.g., in the driver’s cabin of a loader) — to make it possible to distinguish compostable from non-compostable items. Brands have established standards, such as logos, colors, and images, that communicate their messages, which are a significant consideration. And consumers and end users are the ones who make the decisions about which bin to put their products and packaging in after use. “For composters, consumers and end users, the litmus test for our recommendations is: Will it check the box on ‘readily and easily identifiable’ by the user and the composter,” states Wendell Simonson, BPI’s marketing director who oversaw development of the Guidelines.

The final set of considerations covers manufacturing limitations, market preferences and financial impacts. These, combined with “will it check the box,” are where the rubber meets the road, or as BPI states, these three factors “drive the feasibility and timeframes associated with the labeling and identification strategies recommended in Part Two of this document.” The factors are:

“First, many of the strategies that are called for are not in practice today and will require significant time and investment to implement. The recommendation to manufacturers and brand owners is to follow a phased approach, starting with categories where manufacturing and technology limitations are not present.

“Second, certain market preferences are determining factors for how many compostable items are produced. For example, adding color to clear items will fundamentally change the value proposition (e.g., ability to see the food inside), and there may be scenarios where conventional packaging will be used instead of compostable packaging if design elements like striping or tinting are required.

“Third, the investments required to implement some of the recommended strategies will significantly change the economics for manufacturers and brand owners, and some of those costs are likely to be passed on to their downstream customers. Compostable products and packaging are already sold at significant premiums relative to their conventional counterparts, and it is possible that the labeling and identification approaches proposed here will increase those premiums. This could lead to reduced market acceptance of these items.”

BPI Recommendations

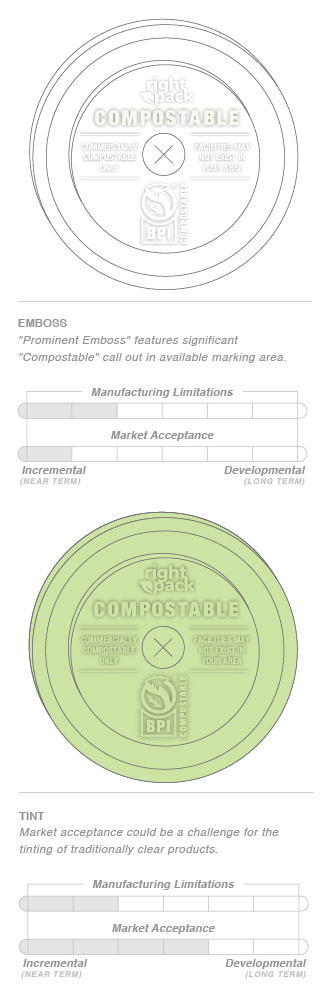

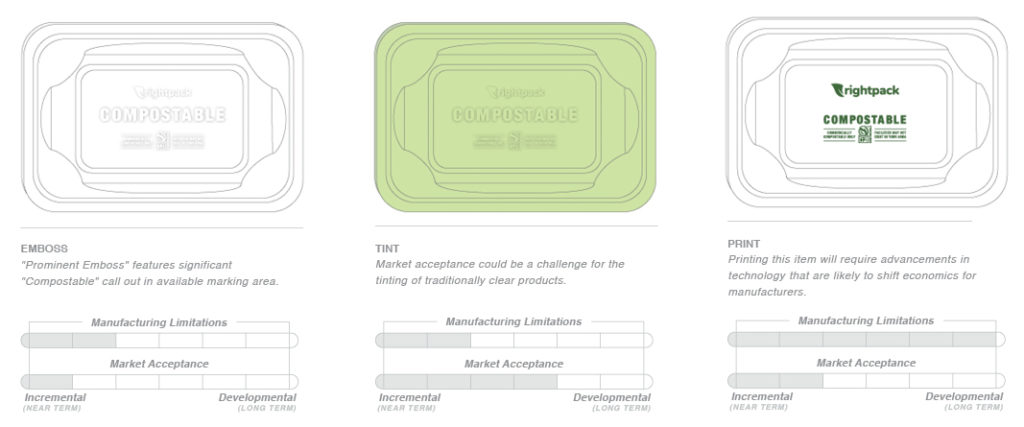

Part Two of the Guidelines provides specific recommendations for the labeling and identification of compostable products and packaging, recognizing that products and materials may have different options. There are two sections: (1) A comprehensive chart displaying the full set of labeling and identification techniques available, by category and material type; and (2) A set of mocked up illustrations designed to make the recommendations in the chart easier to visualize, accompanied by estimates of availability based on Manufacturing Limitations and Market Preferences. “These illustrations are examples of what finished products might look like when the recommendations for labeling and identification by category and material type are put into practice,” explains BPI. “The brand names used are fictional placeholders designed to make the illustrations look more realistic.”

To the right of or below every example is a set of two “sliding scales” with additional information on the labeling and identification technique(s) illustrated. The “Manufacturing Limitations” sliding scale is designed to give the reader a sense of current availability and estimated future availability based on the investments required to achieve the recommended labeling and identification method. For example, adding or changing embossing requires that new molds be made and installed for every shape and size of a given product, notes BPI. Adding color will require identifying inks and colorants approved by the Food & Drug Administration, as well as recertifying the products with BPI. “Recertification is required whenever new ingredients are added to the formulation,” explains Simonson.

The “Market Acceptance” sliding scale is designed to give the reader a sense of how the recommendations may be viewed by customers in food service and retail marketplaces today. “For example, transparent packaging is often used with fresh foods recognizing that consumers ‘eat with their eyes’ and may want to see the food to confirm freshness,” state the Guidelines. “Switching to a tinted package may help with labeling and identification for composters, but this may not be acceptable for brand owners and their consumers.”

Adds Simonson: “Sometimes the viewability attribute is more important to the purchaser than the compostable attribute. Part of why the guidelines are set up to contextualize the manufacturing and market acceptance factors is to educate stakeholders such as composters about the constraints. Everyone concurs that steps must be taken to improve labeling and identification of compostable products and packaging. But that is not as simple as just flipping a switch.”

Barriers To Change

The bioplastic cold beverage cup (Figure 1) and the bioplastic coated paper hot beverage cups are examples of where the barrier to improve the labeling and identification is fairly low. Both items are widely printed today. The only thing to change is what they are printing. “In terms of ground we can cover the fastest, the places where printing is done today offer the quickest chance to do the right thing and do it consistently,” explains Simonson. “This is where BPI can provide direction on what brands and manufacturers do in terms of the language — the ‘compostable call out and disclaimer’ — and use of the BPI logo (Certification Mark) and color. If all brands would all use the same language on the same part of the cup, along with the BPI logo, that would bring much needed consistency to the marketplace. Manufacturing is not a hurdle.”

The lids for cold cups and hot cups (Figure 2), on the other hand, are a different story because printing is not a viable option for either, and the efficacy of tinting and/or material coloring depends on certain colors like green and brown being carved out by regulators as “compostable only” colors. That leaves a prominent emboss strategy as the most available option in the short term, but a “significant” compostable call out is challenging given the space constraints on a lid or on a piece of cutlery.

Unlike cups, clamshells (Figure 3) have a higher barrier to change. The technology doesn’t exist to print on clamshell lids. Embossing would enable the labeling to be prominent (“features significant”). “Prominent emboss means it can be seen easily during the use of the product, so it should not be hidden on the bottom of a cup or clamshell,” says Yepsen. “And the text would need to be larger than if printed to make sure it’s not difficult to quickly identify.” Tinting and coloring, as noted earlier, are feasible, but market acceptance is a significant hurdle.

For items like portion cups (Figure 4) and round deli containers, printing is “operational” today, but manufacturers are not printing these items. Embossing has fewer manufacturing limitations. “The shortest term play for a lot of these items is doing better embossing,” adds Simonson. “We are trying to get a feel for whether that will work. Manufacturers will need to make new tools. But the bigger picture question is whether more visible embossing will check the box on ‘readily and easily identifiable’ for the user and composter.”

There is no doubt that these new BPI Guidelines will elevate the understanding of all the moving parts involved with improving the labeling and identification of compostable products and packaging. The visuals, and the manufacturing limitations and market acceptance sliding scales, create a realistic framework for weighing alternatives and next steps. “We’ve invested the time to learn what will truly be required for consumers, end users and composters, and balancing that with the brands and manufacturing sector’s realities and limitations,” observes Simonson. “The Guidelines lay out all the options and will get the conversations started.”