Top: Brenda Platt, Institute for Local Self-Reliance. Photo by Miriam Doan

Molly Lindsay

It has been over a decade since composting became a central focus for the Institute for Local Self-Reliance (ILSR). What started as part of the Waste to Wealth initiative, Composting for Community later branched off, led by Brenda Platt, who has been with the Institute since 1986.

In 2013, ILSR held the first “Cultivating Community Composting Forum” in partnership with BioCycle in Columbus, Ohio. It was spurred by the growing number of community composting sites in the U.S. The forums have taken place yearly since then, with an increase in interest after the publishing of Growing Local Fertility: A Guide to Community Composting by ILSR and the Highfields Center for Composting in 2014. Since then, a coalition of community composters has formed and continues to grow.

ILSR advocates for establishing small-scale and decentralized composting systems rather than larger, industrial-scale facilities. To help further this model, the Institute has created a robust series of webinars, training programs, infographics, and studies, along with many other resources for new businesses, interested folks, or communities looking to learn more. To wrap up the “Lessons in Community Composting” series that began in March 2020, I spoke with Platt to gain insights into the business of community composting and the state of the industry today. [This interview has been edited and condensed.]

National Numbers

Lindsay: ILSR has been tracking community composters since at least 2013. How many community composters are there in the U.S. today? Do you have a sense of how many are at community gardens and farms, versus a stand-alone composting operation in a neighborhood?

Platt: As of October 2020, ILSR has 198 community composters featured on the Composting for Community Map. A community composter can encompass more than one category such as a microhauler and a worker-owned cooperative. There are 56 operating at community gardens, 31 at urban farms, and 4 at other farms. Nine are technical assistance and education sites and 6 are located at universities and colleges. This count is not indicative of the number of community composters operating in the U.S. Many more exist than are currently being tabulated.

Lindsay: Can you estimate how many community composters also offer a collection service?

Platt: There are 56 microhaulers among the total group of community composters, and of that number, 25 are bike haulers.

Lindsay: Does ILSR track how many tons of food scraps are diverted to composting through the community composting infrastructure?

Lindsay: Does ILSR track how many tons of food scraps are diverted to composting through the community composting infrastructure?

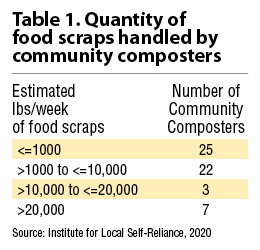

Platt: We are working on a census of the community composters that will highlight tonnage diverted through their operations. The data in Table 1 is based on applications to join the Community Composter Coalition. Between February 2019 and October 2020, 57 applicants had estimated the quantity of food scraps they handle weekly.

Business Of Community Composting — Making It Work

Lindsay: What are the top three challenges that community composters currently face?

Platt: The top three challenges are market development and sale of compost products, lack of equipment designed for the community composting scale and insurance. Insurance has come up repeatedly — if you’re a bike hauler that has to have the same level of insurance as a trash hauler, you just can’t do it. Other challenges are access to land for operation and volunteer coordination for organizations that rely on that labor.

Lindsay: What are solutions to combat these issues?

Platt: ILSR will be offering a series of webinars to address the top three challenges. The webinars are in lieu of the annual Cultivating Community Composting Forum that was scheduled for 2020 but was cancelled due to COVID-19.

Compost markets and sales: The compost product market development and sales webinar will feature presentations on markets such as compost socks for storm water and green infrastructure, and selling to medical marijuana growers. Another avenue for compost sales is local government and state procurement. We used to say in the recycling field that if you’re not buying back recycled products, you’re not finishing that recycling. We should be pushing for local and state governments to buy locally produced compost. Some exemptions or leeway will be necessary to make it easier for community-scale composters to distribute and sell their compost to governments, as procurement caters more to larger scale composting operations.

Equipment: With equipment, it’s a mixture of connecting with manufacturers to showcase the needs of this growing market, as well as featuring what’s available now. Community composters can also get creative by building their own equipment to suit their needs. For example, Eco City Farms in Maryland and BK Rot in Brooklyn have built trommel screens. Through our census, we’re planning to find out what brand of buckets or compostable liners composters are using to potentially create a buying co-op for coalition members.

Insurance: As for insurance, I don’t have an easy answer. There’s no NAICS (standard industry) code for composting; it’s under fertilizer manufacturing, or trash hauling. We would like to bring insurance experts together to see if a possible solution is to pool insurance coverage under an umbrella plan for members of our coalition to bring the costs down.

Lindsay: Is it important to diversify — i.e., offer collection and processing or just hone in on one aspect?

Platt: Generally, I think it’s always good to diversify business, so the answer is yes! The theme of the 2020 Forum would have been “Sustaining Your Operation.” A lot of the organizations in our coalition are mission-driven — they want to offer benefits and paid time off, but at the same time to make ends meet so many workers have side hustles. Increasing earned revenue and setting up your model so you’re not getting it from one place, as well as having diversity in your client base, is really important. Think outside the box in terms of the products and services you offer. For example, many businesses had to pivot during COVID-19, like Compost Cab of Washington, D.C., which started Brijit, a distribution service of products from local, women-owned food businesses.

Explore what kind of partnerships you can develop that will increase sales and be ongoing. The key is not growing so fast that you lose on the quality of your products. You can’t let the sales and money get ahead of losing your reputation.

Lindsay: What are the benefits of different business structures, e.g., for profit vs. nonprofit?

Platt: There are pros and cons to each approach. You have to figure out what your mission is, and what are your goals. For example, do you have built-in volunteers for the nonprofit model? Are you engaging youth?

A worker-owned structure is a mini democracy where workers buy-in for ownership, like Fertile Ground in Oklahoma City. Employees have a vested interest in the company and it’s a way to jump start your capital investment. As a nonprofit, you can get foundation grants. And if you’re going to be doing a lot of educational programming, training, operating a demonstration site, and/or working with community gardens, then it might make sense to go the nonprofit route. If you’re primarily a food scrap service provider, you have a built-in revenue model where it would be more sustainable to get collection fees from the generators and be a for-profit entity.

ILSR offered a webinar on this topic with the Sustainable Economies Law Center, “Entity Structure for Community Composters”.

Equipment For Community-Scale Processing

Lindsay: Compost processing can be an equipment intensive business. Do you have suggestions on how to access or raise capital to purchase such equipment?

Platt: Financing for equipment is a challenge that frequently comes up for community composters. We’ve done webinars featuring organizations that have crowdfunded. Lor Holmes of CERO in Massachusetts presented on how its worker-owned cooperative raised over $350,000 through a Direct Public Offering funding campaign.

State grant programs may also be a funding source. For example, New Jersey and Pennsylvania have a per ton surcharge on landfills and disposal sites that go to state grant programs that fund equipment purchases. Two Particular Acres in Pennsylvania was able to use this method for much of its equipment purchasing.

Foundations can help with financing, which is one of the benefits of being a 501(c)3 nonprofit. If you’re a farmer, many states offer funding programs. Thinking outside the box, companies have rented vehicles for collection instead of purchasing them. There are ways to avoid buying a lot of equipment. Instead of owning a trommel screen or chipper you can rent one for a few days or weeks and process material all at once.

Top: Skid steer loader. Middle: Small trommel screen. Bottom: Rotochopper Go Bagger for compost bagging. Photos by Molly Lindsay

Lindsay: What equipment can really give organizations the best bang for their buck?

Platt: One example I love is Red Hook Community Farm in Brooklyn (NY), which is fossil fuel free. It has an aerated static pile (ASP) system powered with solar voltaics and operates with hand tools, so the facility is off the grid. A larger scale system is going to need some kind of equipment to move and manage its piles, e.g., a skid steer or bucket loader. It’s the same equipment that the large-scale operators need. Procuring a trommel screen that’s affordable will save a lot of labor. Other than small skid steers, the Sittler trommel screen and Rotochopper Go-Bagger 250, for bagging finished compost, are used at small-scale operations.

In a more rural setting, aerated static piles can be used to cut down on labor and pile turning. In an urban environment, where there’s more risk of rat issues, that can be more challenging and you really need to manage correctly and carefully. A three-bin system is great if you have volunteer labor to help manually flip piles, but with disturbances in normal operations due to COVID-19, having volunteers help out is challenging and that’s where having an ASP set up or equipment to help mix the piles is worth it.

On the collection side, having a decent vehicle that can haul material is critical.

Prioritizing Best Management Practices

Lindsay: What are the best practices for a community composter who is having trouble gaining traction in their community?

Platt: If you’re composting, people smell with their eyes — you want to have a site that’s aesthetically appealing and follow best management practices. Minimize clutter, have educational signage, and if you’re a drop-off site, post clear directions for how to participate. You want it so you can bring an elected official there and say I want to do more of this; help us grow. Make sure that it doesn’t smell, and there aren’t unwanted critters or other public nuisance issues. Growing plants around the site with your compost is great because you’re trying to sell the soil amendment. Produce high quality compost, test your compost, and make sure to follow the process to further reduce pathogens. For more suggestions, check out ILSR’s Community Composting Done Right: A Guide to Best Management Practices.

Emphasize community benefits. For example, if you’re producing “black gold” to help grow local food, you’re addressing food insecurity. Or maybe you’re converting blighted sites to green space and improving neighborhoods. Community composters are so small scale that often they are benefiting the community. With composting at the industrial-scale, there’s more traffic in and out and those sites may have a bigger challenge getting community buy-in and avoiding “not in my backyard” reactions.

Lindsay: What about best practices for collection?

Platt: Getting more clients requires marketing and outreach. Baltimore Compost can advertise that the compost is going back to local gardens and benefiting the community and the former Compost Pedallers of Austin had a points program where the weight of your food scraps translated to points that could be used for discounts and specials at local businesses. Be creative, think outside the box. There are so many ways to drive business depending on what the opportunity is. Bike haulers have an advantage because hauling by bike is so cool and some have a trailer with space where local businesses can advertise.

Lindsay: How do you foresee the community composting movement evolving in the next 5 to 10 years?

Platt: I think we will see more food waste reduction, food rescued to feed people as well as recycling into compost, because we have to. If we want to help mitigate climate disruption, we need to get carbon back in the soil. Community composting is foundational to that because there really is no obstacle to do it on a small scale and it’s in the same community as where the materials are generated. You have to set people up for success with best management practices, training, and right-sized equipment. Local government will be absolutely critical for access to land, financing, education, and marketing, and also not competing directly against small-scale operators, but supporting this diverse infrastructure.

Addressing a lot of the challenges will help this sector grow. The main way to get more traction is connect it with what people care about. If you’re greening neighborhoods, you can create local jobs while getting youth involved in the act, keeping them off the street and paying them for their work. Or with food insecure communities, you’re improving soil for food production — it’s all connected. There’s no reason why we can’t have more urban, suburban, and rural farmers doing this and supporting our farming community. More and more states have clear permitting guidelines, but there’s less focus on giving community composters the tools they need, equipment and structure to do it, so I think there’s going to be a lot more partnerships developed.

Molly Lindsay is Director of Operations at the Community Compost Company, a food scrap collection service and compost production company headquartered in New Paltz, New York. She also serves as Editor of Livelihood magazine, a resource for good news on keeping money local, sharing abundance, and strengthening communities in the Hudson Valley.