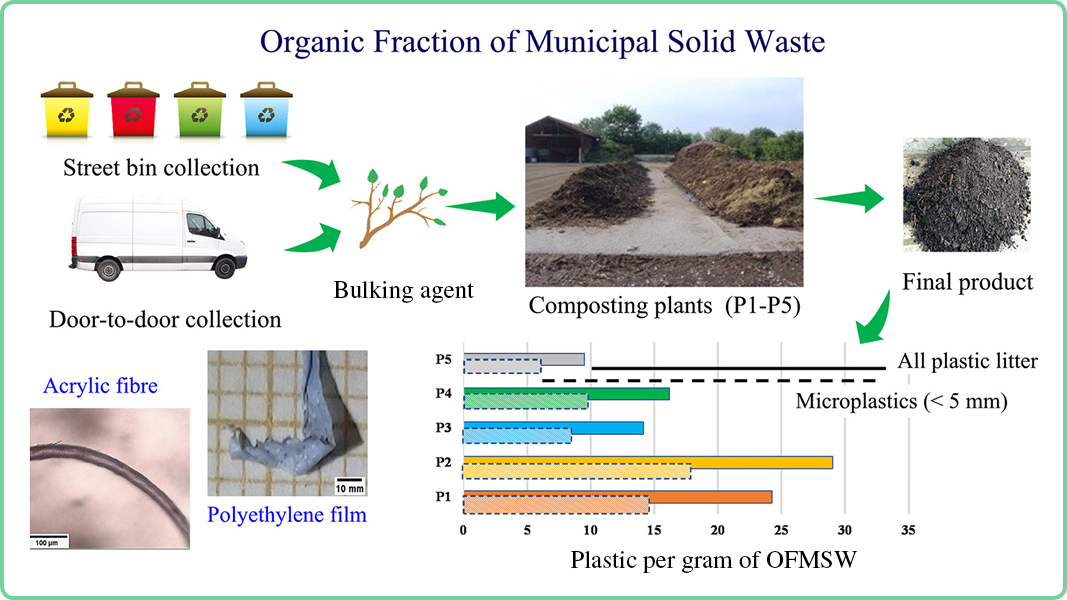

Top: Research study examined how organics collection method impacts the concentration of microplastics in the finished compost. Image courtesy of ScienceDirect.

A paper published in Science of the Total Environment (Nov. 24, 2021), “Microplastics identification and quantification in the composted Organic Fraction of Municipal Solid Waste (OFMSW),” studied the presence of plastic debris in samples of composted OFMSW recovered and treated in five different industrial facilities located in the northeast region of Spain (four composting plants and one using anaerobic digestion (AD) followed by composting). “The purpose was to identify whether the collection and treatment systems affect the concentration of microplastics in the final refined compost,” explain the authors. “The efforts were mainly focused to quantify the number of plastic particles contained in the final OFMSW compost, their typology and polymer composition, with emphasis on the fraction <1000 μm. Special attention was paid to compostable biopolymers due to their role as a tool to promote a high quality collection of OFMSW, especially in door-to-door collection systems.” The samples were taken in five consecutive months in 2021 (from February to June) and consisted of two replicates of about 200 g each per selected plant; they were stored in sealed aluminum bags for transport to the laboratory.

The OFMSW collection systems taken into consideration in this study were based on different combinations of street bin and door-to-door collection. In street bin collection, containers for organic waste are located at curbside and are periodically washed out; collected organics are transferred to the composting or AD plant. “This system does not permit any control concerning the disposal quality and does not guarantee that citizens use compostable bags,” notes the paper. “In door-to-door collection systems, citizens place twice a week their organic waste (small volume, usually 7–10 L) in specific places from where it is collected by dedicated trucks. In this collection system, the use of compostable bags is encouraged or mandatory. In all cases, the waste collected is a mixture of domestic and commercial activities (including restaurants), with higher intensity for the latter in more densely populated areas.”

The presence of plastic was studied using a separation and identification process that consisted of oxidation and flotation followed by spectroscopic identification. The results showed a concentration of plastic impurities in the 10–30 items/g of dry compost range. The concentration of small fragments and fibers (equivalent diameter <5 mm) was in the 5–20 items/g of dry weight range and were dominated by fibers (25% of all particles <500 μm).

Five polymers represented 94% of the plastic items: polyethylene, polystyrene, polyester, polypropylene, polyvinyl chloride, and acrylic polymers in order of abundance. Polyethylene was more abundant in films, polystyrene in fragments, polypropylene in filaments, and fibers were dominated by polyester. “Our results showed that smaller plants, with OFMSW door-to-door collection systems produced compost with less plastic of all sizes,” say the authors. “Compost from big facilities fed by OFMSW from street bin collection displayed the highest contents of plastics. No debris from compostable bioplastics were found in any of the samples, meaning that if correctly composted their current use does not contribute to the spreading of anthropogenic pollution. Our results suggested that the use of compostable polymers and the implementation of door-to-door collection systems could reduce the concentration of plastic impurities in compost from OFMSW.”