Top: The smokestacks of an oil refinery. © Leonard G / Wikimedia Commons (manipulated by BioCycle)

Nora Goldstein

Nora Goldstein

I couldn’t believe my eyes when I read a headline in the The New York Times on May 27, 2022: “G.O.P. Weaponizes Statehouses Against Green Corporate Goals.” The article focuses in large part on state retirement and investment funds that include asset managers that flag “climate change as an environmental risk.” In Texas, for example, “a new law bars the state’s retirement and investment funds from doing business with companies that the state comptroller says are boycotting fossil fuels.”

Similar laws and legislation are being pursued in more than 15 other states across the country, according to the Times. “Republican lawmakers and their allies have launched a campaign to try to rein in what they see as activist companies trying to reduce the greenhouse gases that are dangerously heating the planet.”

Wait, what? Are politicians punishing private sector companies for recognizing that climate change is a threat to their bottom line? More perversely, are they against the triple bottom line of people, planet, profits? We have known about the devasting impacts that business as usual has on our planet for many decades, yet at the federal level and in many states, nothing has been done policy-wise to do anything about it. Cities and some states have taken actions to alter the trajectory. But in many cases, it has been ecoentrepreneurs and those committed to corporate good who have been moving the needle.

Running Your Company Ecologically

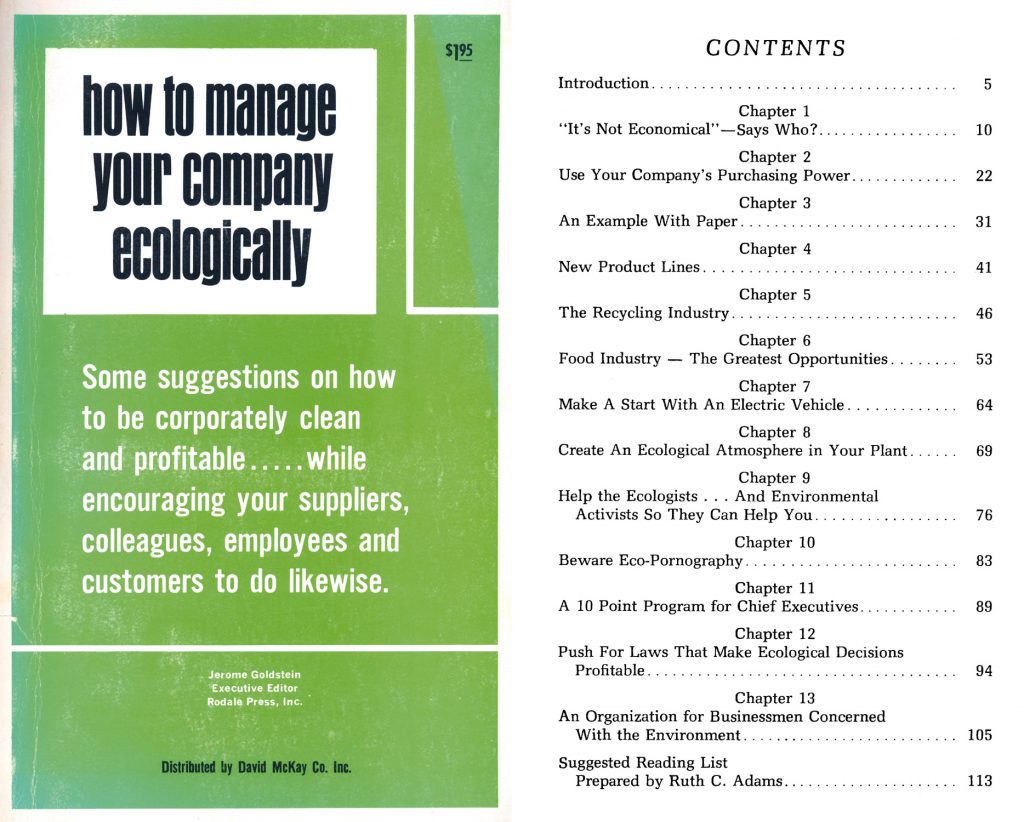

Long before the triple bottom line became popularized, Jerome Goldstein, my father and the founder of BioCycle (originally the journal, Compost Science), saw the connection between people, planet and prosperity. Jerry wrote How To Manage Your Company Ecologically in 1971. The book’s subtitle captures the essence of my father’s thinking at the time: “Some suggestions on how to be corporately clean and profitable … while encouraging your suppliers, colleagues, employees and customers to do likewise.”

I have circled back to How To Manage Your Company Ecologically many times over my almost 45-year career at BioCycle for inspiration, and to remind myself that our company’s mission, and that of so many others across the globe, is to drive positive change through the marketplace, creating green jobs and enterprises that build resilient communities. In fact, eight years after writing How To Manage Your Company Ecologically, Jerry — along with my mother Ina Pincus, sister Rill Ann Miller and myself — launched In Business, a new magazine for ecoentrepreneurs. The eventual subtitle of In Business was Building Sustainable Enterprises and Communities.

This bit of family history helps explain why, in 2022 — 51 years after Jerry wrote a groundbreaking book on the triple bottom line — it is so perverse for me to read that close to 20 states in the U.S. are punishing companies that recognize the importance of using their purchasing and investment power to turn (albeit way too slowly) the tide. Trust me, I am not naïve enough to believe that some of the very companies and asset managers that are divesting holdings in fossil fuel companies are the white knights. But their actions are a tool in our toolbox to pull all the oars on the ship on a corrective path. The reality (and sad) part is we have run out of the luxury of time. The 2020s are the decade of all hands on deck, stat. And anything that purposely creates a roadblock is, quite frankly, abhorrent and self-serving.

This bit of family history helps explain why, in 2022 — 51 years after Jerry wrote a groundbreaking book on the triple bottom line — it is so perverse for me to read that close to 20 states in the U.S. are punishing companies that recognize the importance of using their purchasing and investment power to turn (albeit way too slowly) the tide. Trust me, I am not naïve enough to believe that some of the very companies and asset managers that are divesting holdings in fossil fuel companies are the white knights. But their actions are a tool in our toolbox to pull all the oars on the ship on a corrective path. The reality (and sad) part is we have run out of the luxury of time. The 2020s are the decade of all hands on deck, stat. And anything that purposely creates a roadblock is, quite frankly, abhorrent and self-serving.

Eco-Pornography

Chapter 10 in How To Manage Your Company Ecologically is titled “Beware — Eco-Pornography.” That was Jerry’s term in 1971 for what today is commonly called greenwashing. The chapter begins as follows: “In the desire to put their firms in an environmental pattern too quickly, advertising departments of some companies have raced into print and television with copy that equates current practice with ecological activity. Where it applies, such approaches are excellent. Where it doesn’t the approaches result in what many people refer to as ‘Eco-Pornography’ And with the new environmental awareness, more Americans are sensitive to propaganda-type ads. They’re looking for action, not verbiage.”

Fast forward to 2022, where there is no longer an opportunity to “look for action.” In so many places around the world, we are seeing action, investment and innovation to implement solutions that draw down the dangerous levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. As great as these actions are, it is too little and just about too late. All of these “one-off” solutions aren’t cumulative enough to make the impact we need now.

This brings me back to where I started this Commentary. We don’t have the time, money and energy to fight ignorant, climate-denying politicians who propose and pass backwards policies because they control their state legislatures and thus have the power to do so. Their EcoPerversity is off the charts. As Editor of BioCycle, I endeavor to stay out of the political fray, and instead shine the spotlight on those who have put their money, policies and/or practices to work to make positive and resilient change happen. Now, however, we must use our collective voices to push back hard. In this case, asset managers need to be rewarded for divesting investments in fossil fuel. They control massive amounts of money, and can make a difference.

The Times article describes how Larry Fink, the chief executive of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, has been outspoken about looking “beyond the bottom line.” Fink says there is a sound business rationale for taking up the fight against climate change. The article also points out that BlackRock still has significant assets invested in fossil fuel companies, and is feeling pressured by these state legislators to back off its eco-commitment. In a statement, BlackRock said it would support fewer shareholder proposals calling for climate action because, quotes the Times, “we do not consider them to be consistent with our clients’ long-term financial interests.”

This, too, is EcoPerversity, or as Jerry described it, EcoPornography. It is black and white, with no room for grey. You are either all in, or you are not.