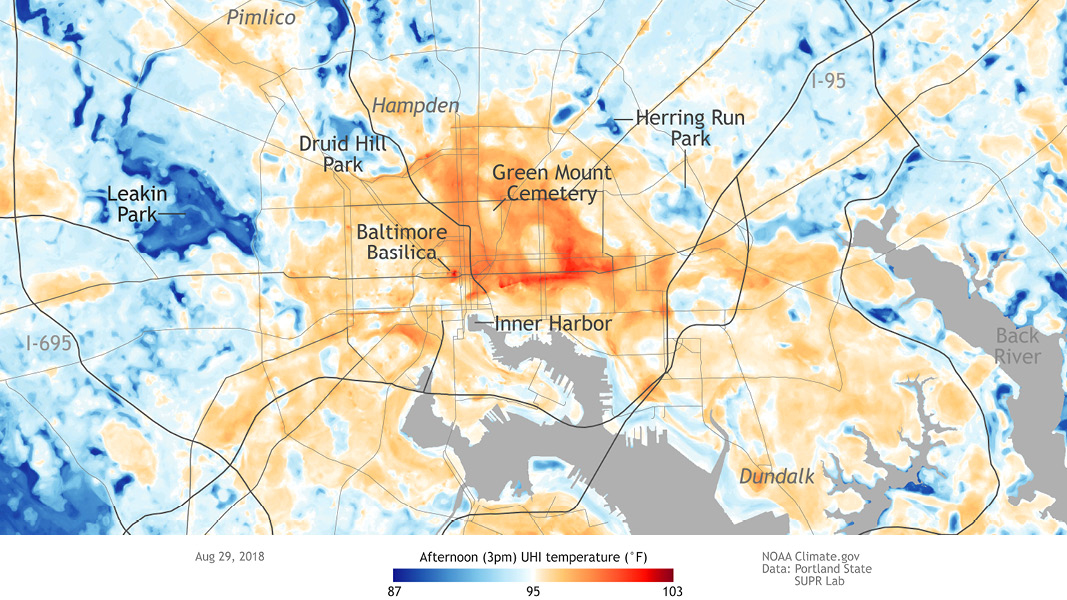

Top: Baltimore Heat Map Image, courtesy of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association

Alondra Sierra and Sophia Hosain

Across the U.S., the effects of 2022’s record high heat temperatures are widespread. While summertime heat waves are common, climate change continues to exacerbate rising temperatures, intensifying heat-induced dangers to the public health and well-being of urban communities due to the urban heat island effect. This effect emerges when the temperature in a metropolitan area is significantly hotter than in surrounding areas.

Heat islands are largely a result of urban development, where materials like concrete and asphalt replace natural vegetation. In a city’s concrete jungle, materials found in buildings, roads, and sidewalks absorb the sun’s heat and emit it back into the air, raising the surrounding surface and ambient temperatures. Waste heat generated from vehicles, industrial facilities, and other human sources also add to the higher temperatures, leading to greater emissions of air pollutants and greenhouse gasses. Urban heat islands pose a serious public health threat to those living in these zones ― often people of color, low-income communities, and vulnerable age groups.

The city of Baltimore, Maryland is a case in point. Baltimore is home to large waste incinerators, and has repeatedly ranked for poor air quality and the worst urban heat among U.S. cities. In 2018, researchers from Portland State University in Oregon found that the hottest heat islands were in the predominantly African American and low-income neighborhoods of East Baltimore, where on a hot day, average temperatures were in the high 90s, reaching up to 103°F. In contrast, average temperatures hit the low 90°s in the more affluent and greener areas of North Baltimore and near Leakin Park in the west. The pattern of urban heat in Baltimore, like many cities in the U.S., echoes the racially redlined development plans drafted in the 1930s, in which largely Black neighborhoods were marked as high risk for investment.

Today, neighborhoods that were considered hazardous for investment are more than 5°F hotter in the summer than the city average, pointing to a disparity in environmental resources such as tree coverage. A recent study evaluating tree equity in urban areas found that Broadway East, one of Baltimore’s hottest and poorest neighborhoods, had 10% tree cover as opposed to northern neighborhoods with much lower poverty rates and anywhere from 50% to 70% tree coverage.

Green Cooling Strategies

Some green infrastructure and waste reduction practices can be enlisted at the local level to help curb the impacts of the warming climate. Cities like Baltimore are replacing gray urban patches with heat-reflecting green infrastructure. Green infrastructure comes in many forms, from tree canopies planted on a sidewalk to forest patches, garden rooftops, cool corridors, and compost application. In the Smart Surfaces Coalition report on Baltimore, adopting practices like reflective roofs, porous pavements, and generous tree planting could cool the city by 4.3°F in peak summer while creating over 75,000 jobs over the next 30 years.

A growing number of community organizations and city-led programs in Baltimore are pushing for more green spaces on barren sidewalks and vacant lots. Since its start, The Baltimore Tree Trust has replaced more than 99,328 square feet of sidewalk with 12,867 trees, according to its website. When planting, if compost is added to the tree bedding, it increases the soil’s capacity to hold water and nutrients. Balanced soil health can help plants develop healthy roots. The resulting green infrastructure acts as a resource and means of beautification that shades neighborhoods, supports healthy air quality, and helps curb heat island effects. In recent years, cities have implemented policies to increase green infrastructure in low-income neighborhoods, and in many cases include compost utilization in their best management practices for its ability to reduce storm water runoff.

Composting For Heat Resilience

Compost is used around trees to improve soil health, retain moisture, and increase the biomass of the plantings. Photo courtesy of NYC Compost Project hosted by Big Reuse

When used as a soil amendment, compost is a prosperous foundation for urban vegetation. When added to tree bedding, it has proven to increase tree growth and carbon sequestration. In a study observing the effects of large-scale urban afforestation in New York City, 56 plots of trees were planted throughout a parkland in Queens, one of the hottest boroughs in the city. Each plot contained 56 trees, half of which were planted with added compost. In a span of three years, the trees planted with compost had more carbon than those without, increased biomass, and showed overall greater growth. The more carbon sequestered in the soil, the less carbon pollutes the atmosphere and propagates urban heat islands. And taller trees supply greater shade to cool streets and buildings ― crucial for households that can’t afford air conditioning and are located in high heat zones. The cooling effects are helpful, too, in reducing energy demand from companies relying on fossil fuel power plants for energy production.

Of course, the benefits of compost extend beyond reducing heat islands through green growth. In Baltimore, where the city’s largest waste incinerator causes more than $55 million in health damages for surrounding residents, compost can be key to alleviating the harmful environmental impact on neighboring low-income communities. Each year more than 430,000 tons of municipal waste is generated in the city ― a quarter of which are food scraps. But through on-the-ground activism, the community is advocating for a zero waste future. In 2020, community members introduced a Zero Waste plan designed to directly benefit Baltimoreans with hundreds of sustainable jobs and environmental regeneration. A significant portion of this plan calls for the diversion of yard trimmings, food scraps, and other organic materials via composting. As the plan states, it is a “stand for social, racial, and environmental justice by declaring that no community can be used as a dumping ground, a sacrifice zone, or a staging ground to burn precious natural resources.”

Instead of organic waste entering landfills and incinerators, major sources of greenhouse gas emissions, the material can be recycled into compost, a valuable soil amendment. The discarded materials turned into compost can provide rich nutrients to support local food systems in community gardens and farms around Baltimore, where the community composting movement is growing. The total diversion capacity for the Baltimore community composting network is 180,352 lbs/year across 10 sites.

The Baltimore Compost Collective at Filbert Street Community Garden in Curtis Bay is a youth-led composting initiative that composts food scraps and garden waste, returns compost to local soils, and creates jobs for local youth.

In 2016, the Institute for Local Self-Reliance (ILSR) launched the Neighborhood Soil Rebuilder (NSR) training program at the Real Food Farm in northeast Baltimore and helped launch The Baltimore Compost Collective at Filbert Street Community Garden in Curtis Bay, a historically underserved and heavily polluted neighborhood. Through robust best management practices, the NSR program supported the expansion of the composting cooperative and youth-led composting initiative, yielding hundreds of pounds of food scraps processed and compost returned to local soils, in addition to creating jobs for local youth. And more recently, the Department of Public Works partnered with ILSR to host virtual at-home composting workshops, bringing the power to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to the residential level.

The planet is only getting warmer from here, and the drastic consequences of urban heat on vulnerable communities will only worsen. But communities can take matters into their own hands to protect their neighborhoods and their future generations through local composting. Urban heat islands may have a surplus of severe effects, but community composting can tackle it with its commanding domino effect: In the process of promoting cleaner air, water, and green infrastructure, it nurtures healthier soils, and more local jobs, local food production, and greener neighborhoods.

This post was authored by Alondra Sierra, Composting for Community’s 2021 Summer Intern, and Sophia Hosain, the Institute for Local Self-Reliance’s Composting for Community’s Baltimore Lead.