Top: Photos courtesy Harvest Pierce County

Sally Brown

Sally Brown

Part I of this Connections series on contaminated soils and environmental justice reviewed common soil contaminants and pathways to human exposure, and teased apart the debate on whether or not it is prudent to plant in these soils. So now you are somewhat well versed on the issues of contaminants in urban soils, how they relate to environmental justice, how green space compares to brown in terms of public health and happiness, and how the contaminants can do harm. In deciding on the best approach then, one might be tempted to look at regulatory limits. These limits should reflect what the experts have deemed to be safe.

It turns out that doing that just muddies the waters. Depending on where you look you can find a wide range of numbers. For many cities and soils, the limits in the guidance are well below the numbers in the neighborhoods. What do you do then? You can’t just excavate a zip code. In many cases, these different numbers are accompanied by different suggestions on a best course of action. All too often the numbers are just presented with no recommendations.

If we go way back to the start of this discussion, Malone used a value of 14 parts per million (ppm) for soil lead (Pb). It likely took some digging for her to get that number — it is an EPA Ecological Screening level. According to EPA, these screening levels are not meant to be viewed as levels of concern. If they were, we’d be in big trouble. A soil survey by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) measured mean and median soil lead at 18.1 and 25.8 ppm, respectively, in close to 5,000 samples collected across the U.S. (Smith et al., 2013). EPA has separate Pb concentrations for commercial (1,200 ppm) and residential sites (400 ppm). Lower values are for sites where you would expect kids to play. The higher values are where you would expect people to work.

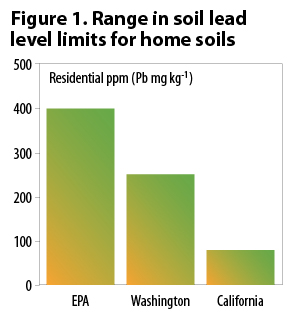

It turns out that a number of states don’t think that those values are quite low enough. With the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) lowering acceptable children’s blood concentrations from 10 to 5 ug per deciliter, California went to 80 ppm as a safe number for home soils. Where I live in Washington state, we split it down the middle, coming in at 250 ppm (Figure 1). In other words, regulatory limits to keep us safe from Pb in soil ranges from 14 ppm (EPA ecological screening level) to 1,200 ppm (EPA non-play or commercial soil level for humans). For any normal person, this range will lead to uncertainty and confusion.

It turns out that a number of states don’t think that those values are quite low enough. With the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) lowering acceptable children’s blood concentrations from 10 to 5 ug per deciliter, California went to 80 ppm as a safe number for home soils. Where I live in Washington state, we split it down the middle, coming in at 250 ppm (Figure 1). In other words, regulatory limits to keep us safe from Pb in soil ranges from 14 ppm (EPA ecological screening level) to 1,200 ppm (EPA non-play or commercial soil level for humans). For any normal person, this range will lead to uncertainty and confusion.

The same is true for polyaromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) concentrations. In most cities, regulatory limits are lower than what is actually in the soils. Site specific clean up goals typically range from 0.1 to 1 mg kg BaP equivalents (Ruby et al., 2016). Researchers found average concentrations in Detroit and New Orleans of 7.84 and 5.1 (BaP equivalents) ppm, respectively (Wang et al., 2008). In many cases, these limits are set without providing any guidance on next steps. In fact, in the paper that I mentioned early on (Jiao et al, 2015) where they describe environmental justice in the context of the neighborhood in Columbus, Ohio, they tested people’s soils and gave them a website or a number to call if they wanted more information. No other tools were provided. Granted, most of the soils they sampled were under the U.S. EPA and Ohio value for Pb of 400 ppm. But if these people had seen the Malone paper or the limits in California, they would be digging scared, or not digging at all.

Now in my mind, telling someone or some city that their soil is poison and not giving them options on what to do about it is the furthest thing from environmental justice. It’s more like environmental torture. Some places do provide guidance, but just like the regulations, the guidance is far from clear. Lupolt et al. (2022) surveyed the 40 largest cities in the U.S. for Soil Safety Policies (SSP) on lead in soil in relation to urban agriculture. They found varying levels of guidance with inconsistencies in how much Pb is safe and advice on appropriate behavior to mitigate exposure. Seven cities required soil testing but only five provided guidance or threshold values. Some guidance applied only to commercial growers while others applied only to participants in particular programs. Six of the policies applied to all urban agriculture. Guidance values for Pb, when they were provided, ranged from 34 to 1,200 ppm.

What To Do?

Here there is consensus that the best thing to do is get new soil. That is much easier said than done. Soil takes a very long time to make — thousands and thousands of years — and it is near impossible to order it in sufficient quantity on Amazon to cover Brooklyn. Scientists in New York City have started a clean soil bank where they ‘harvest’ soil from construction sites. In Ohio, they recommend using dredged sediments (only if they are not more contaminated than the soil itself). It also helps if they are dredged from freshwater systems. I don’t see folks just giving the Army Corps of Engineers a call though, saying ‘Hi I’m over on the west side and was wondering if you have any sediment you might share?’ One of the experts in the field of soil Pb, Howard Mielke, found a silver lining in Hurricane Katrina. So much sediment washed on the ground during the storm that soil Pb levels dropped like crazy. Here, while it is great that something good came out of that disaster, I don’t imagine that silver lining is enough to get people wishing for more Category 5 hurricanes.

A number of researchers, myself included, have shown on multiple soils with levels of contamination to match multiple limits, that adding composts and biosolids soil products is a real world, practical answer. These ‘soils’ are or can be made every day in every city. A group out of Kansas State University lead by Ganga Hettairachchi tested different composts on contaminated garden soils across the U.S. They found that the composts diluted the concentrations of the contaminants. In many cases, they also made the Pb that was in the soil more insoluble, or less able to do harm. Plants in the composted amended plots were often bigger than the controls, and just as often had less Pb. Ganga, Rufus Chaney and I wrote a paper that basically said that growing gardens in compost was a way to get lots to eat, plenty of flowers, and to take away any concerns about soil contamination. I summarized that paper in a 2016 BioCycle column. Even researchers that advocate for clean soil also recognize the value of these materials when you can’t just call the Army Corps of Engineers.

Howard Mielke, the same guy that found the silver lining in Hurricane Katrina, was up in Seattle visiting his daughter. He and I met up at the Tacoma (WA) wastewater plant for a tour. We went to one of the community gardens that is part of the Harvest Pierce County program. Tacoma is the home of a former smelter, meaning that lead and arsenic contamination of soil is common place. It is not a well-to-do city, although it has hosted its share of Seattlites looking for somewhere to go. Each of the gardens gets as much biosolids-based potting soil (Tagro) as they need.

Tagro is one of the amendments that had been tested by Ganga in her trials. Tacoma community gardens get soil testing and they get materials to build raised beds. Cardboard is provided to put on the walkways along with chips made from recycled wood to put over the cardboard. This keeps the dust and weeds down and also creates a barrier from any non-tended soil. Dr. Mielke took several bags of Tagro for his daughter’s house. He was really impressed by the program and upset that in New Orleans, his hometown, they had to rely on the hurricane to clean the soil. There is no municipal composting in New Orleans and all of the biosolids are incinerated. Tacoma is an example of a proactive solution to issues of soil contamination and environmental justice. It is a real-world example for the vast majority of us who can’t just find clean soil.

I was very happy to see a paper, written by people with no access to Tagro, that basically argued the same point (Schwarz et al., 2016). The authors address vacant abandoned lots in shrinking cities and recognize that they are typically seen as a barrier to urban agriculture as a consequence of likely contamination. They argue that gardening in these lots, with the requisite tools to improve the soil, is the solution to the problem. Tending to the soil will dilute the contaminants, tamp down the dust and also provide multiple environmental benefits. In contrast, it is not clear that leaving those lots barren will do more good than harm. In other words, these benefits go further towards addressing environmental justice than any other option (related to soil contamination). Yet again, compost is the answer.

Sally Brown, BioCycle Senior Adviser, is a Research Professor at the University of Washington in the College of the Environment.