Top: Photos by Sally Brown

Sally Brown

Sally Brown

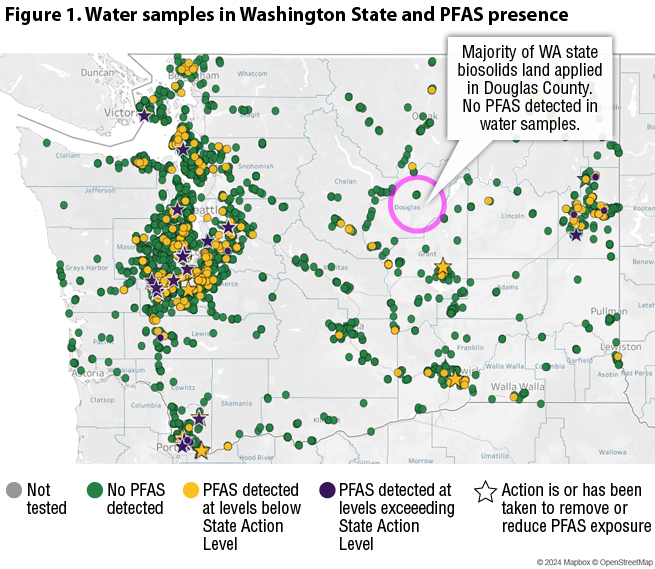

The New York Times (NYT) is continuing its reporting on PFAS and sewage, and BioCycle is continuing its analysis and response (see Part I). The latest installment was published September 21 (Tabuchi, 2024). The take home message once again is that sewage is poison and it is being spread everywhere. You read the article and conclude that banning the biosolids is the way to get rid of PFAS once and for all. While there are some true statements buried in the piece, it starts with a big whoopsie. The reporter notes that sludge is spread on millions of acres of farmland each year, citing a 2018 national biosolids management study. Actually, while there are about 2.7 million acres permitted to receive biosolids, there are only 182,000 acres where biosolids are actually applied, which reflects how much biosolids touches soil. This is a much smaller number that clearly is too low to qualify as everywhere — and nowhere near enough to be the root of the problem we are now facing. This reality is illustrated in Figure 1.

Graphic courtesy Washington State Department of Health

The NYT article focuses on a family farm in Maine. The family eats beef from the organic family farm that, you guessed it, had toxic sludge applied years back. Likely as a result, the kids have elevated PFAS in their blood. This is a terrible thing to happen to anyone. No argument there. The argument is in how to best reduce PFAS exposure for everyone, including this family.

Getting To The Source

Realize that there simply is a tiny minority of biosolids with enough PFAS to pose a concern, and everyone has PFAS in their bodies already. This is the case whether or not they have ever been near a wastewater treatment plant or a pile of biosolids. This is true even if they live in a state where all biosolids are burned (talking about you, Connecticut). This is the case even if they eat only organic food. It is not only in our (U.S.) blood. A recent study that sampled corpses in Spain found PFAS in brain, lungs, kidneys and bones. Granted, the concentrations of the two prohibited compounds (PFOA and PFAS) in our blood have gone down since their use has been phased out, but it isn’t like our blood is as pristine as rainwater. Come to think of it, the rainwater has PFAS in it too. Clearly the problem goes way beyond a few water reclamation facilities.

No one, not even people that like and use biosolids, want forever chemicals coursing through their blood. Pointing the finger at the toilet or treatment plant is missing the point. Understanding the varied sources of PFAS and the varied ways we are exposed to them is the way to understand the extent of this crisis and to find a way out of it.

Bottom line: Our PFAS exposure is not that simple.

There are a few facts that the NYT’s second article gets right. The family that is the focus of the article was exposed to PFAS through historic uses of now prohibited compounds. The high concentrations of PFAS, likely PFOA and PFOS on the family farm, were from legacy uses of amendments. The family is in Maine, and Maine is ground zero for sludge and PFAS. That is because the primary source of PFAS in Maine was papermill sludge from producing coated paper, primarily for food packaging. At least one of these mills discharged into a municipal wastewater treatment plant. What has happened to this family and to the other 60 farms in Maine that have been impacted is awful. We absolutely should work to identify farms that have been impacted by chemicals that were used in the past.

Another part of the NYT article that rings true is the acknowledgement that these forever chemicals, the ones still being made, are “widely used in nonstick cookware, raincoats, firefighting gear and other products.” The reporter also says that the government suggests that the most common routes of exposure are likely eating foods and drinking water that are contaminated. Note here that the vast majority of contaminated foods and drinking water have not been anywhere near biosolids or wastewater. Think airports and military bases. Because PFAS are everywhere and in everything (a gross generalization that isn’t too far off) it is difficult to ascertain exactly what the most important sources of PFAS are. The exceptions are cases, like the family in the NYT article, where there is a clear point source. Thankfully those cases, at least those associated with biosolids, are the rare exception. For the bulk of us, it is a question of teasing out which of the many potential sources are the most important.

Pathways Of Exposure

A way to start is by going over how that PFAS lurking in various places in your house can potentially enter your body and perhaps cause you harm. These are the ways that PFAS has a chance of being absorbed:

- Inhalation: Breathing in particles that contain PFAS, such as household dust.

- Ingestion: Eating or drinking liquids or solids that contain PFAS. Food and water are the obvious culprits here. Also realize that you may unintentionally eat some of the paper that your sandwich came wrapped in.

- Dermal adsorption: Touching something that contains PFAS and having the PFAS absorbed through your skin. Different types of cosmetics would fit into this category.

Of all of these, the water category is the most direct. People drink water at home. They use water to cook with. Water is a main ingredient in both coffee and tea. In addition to drinking water, water also comes into contact with your skin. Every time you take a shower or a bath you come in contact with water— hopefully nice and hot water but still water even if it is low pressure and tepid. Water as an exposure pathway is one that you experience multiple times a day, every day. You also typically are exposed to the same water day after day except for maybe that Alaska cruise vacation or that VRBO at the ski resort.

Nonstick pan

Here I am getting at something that I alluded to earlier in this column. For the PFAS in any particular medium — be it your nonstick pan or your lipstick — the frequency of exposure is critical. Here is another point that the NYT article got right. The family who was the focus of the piece ate beef each week from the same farm with the high historic PFAS contamination. A single, high PFAS source that was a regular exposure pathway. If you use your Teflon pan for every meal and eat most meals at home, it will be a much more likely source of PFAS to your system than if you leave it in the cabinet and eat takeout.

Stain-resistant carpet

If you get takeout rather than eating home cooked every day, there is a much higher likelihood that the packaging from your burger and fries will be a significant source of exposure for you. If you’re like my friend Leslie’s mother, who wouldn’t take out the garbage without a full face of makeup, that makeup may be a likely source of exposure. For me, who still has the original tube of lipstick that I bought in my twenties (Cherries in the Snow), that exposure route is much less significant. My pet-resistant carpet is likely my primary source.

Drinking water

Water is also a strong example as a number of communities have drinking water high in PFAS. These locations can serve as case studies. One paper I read measured PFAS in breast milk for mothers in Uppsala, Sweden where the drinking water had been contaminated from use of fire-fighting foam (Miaz et al., 2020). With a predominant source of exposure, it makes it much easier to understand how much PFAS we absorb and how long it stays in our bodies.

Household dust

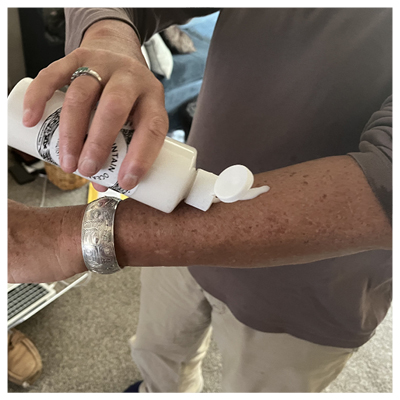

PFAS in dust can make it through your skin. Apparently, applying moisturizer serves as a barrier, according to researchers.

Other exposure pathways aren’t so obvious. Take household dust for example. It can be inhaled or ingested. Those are clear pathways for the PFAS in your dust to get into you. Can PFAS also work its way through your skin? Does that depend on which of the many versions of PFAS you are talking about? Another study looked at dust and cosmetics to see if the PFAS in dust could be absorbed through your skin and if what you put on your skin had an impact. To do this, the authors developed a laboratory test to mimic skin using manufactured sweat. It turns out that PFAS in dust can make it through your skin. Apparently, applying moisturizer not only keeps your skin young looking, it serves as a barrier for PFAS (Ragnarsdóttir, et al., 2023).

This discussion has likely made you a bit jumpy. You may be dusting as you read it, with that almost forgotten COVID mask on your face. You may have ordered a new set of iron pans and put the nonstick in the giveaway pile. In addition to the disservice the NYT series has done to municipal biosolids, they have also done a big disservice to people in general. While this latest article has a few true points, they are lost in the sensationalist reporting. Responsible journalism would make it clear that we are all victims of PFAS, that it is a complicated issue and that the one, clear way to reduce the hazards associated with these chemicals is to stop using them in seemingly every product known to man.

Sally Brown, BioCycle Senior Adviser, is a Research Professor at the University of Washington in the College of the Environment.