Top: The price of eggs are directly impacted by outbreaks of avian flu. Photos courtesy Sally Brown

Sally Brown

Sally Brown

Many say that it was the price of eggs that decided the election this past November. You could call that “Cheaper by the Dozen.” Depending on your perspective “The Dirty Dozen” might also come to mind. Humpty Dumpty anyone? At this point it is not clear if all the King’s horses and men will be able to reassemble the country. Let’s see how and if, organics might provide some glue.

In all (not counting backyard birds), the U.S. produces 117.5 billion eggs each year or about an egg a day per person. Those eggs are laid by between 365 million and 400 million chickens. Egg production is fairly well distributed across the U.S. Egg prices started climbing because of an outbreak of avian flu aka HPAI or highly pathogenic avian influenza. When avian flu is detected in a flock, all of the birds have to be killed. There was a big outbreak in 2014-15 and our current bout has been ongoing since 2022. Layers are more susceptible to HPAI because they are often kept in large facilities. If one bird is sick in your flock of five, all have to go. The same is true if your flock numbers in the hundreds of thousands. Commercial laying facilities often have more than a million birds. Dead birds mean fewer chickens. Fewer chickens mean fewer eggs. And fewer eggs mean more expensive by the dozen.

Mortality Management

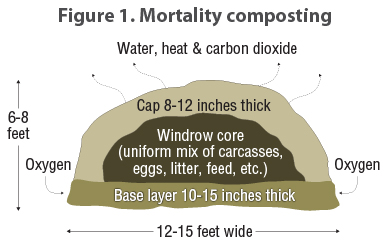

The first place that organics fit into this picture is at the end of the road — for the chickens, that is. Mortality composting is the most common way to repurpose dead chickens. This became the case in the 2015 epidemic with the U.S. Department of Agriculture supporting composting as the most environmentally friendly end of life option for the birds. You can read about it here. My quick search found multiple examples of state guidance for how to compost dead chickens. On farm composting is the recommended option (Figure 1) as transporting the carcasses off farm increases the potential for disease to spread. You can layer those dead layers with manure and a high carbon material. Sawdust and straw are two examples. Add water as needed.

The first place that organics fit into this picture is at the end of the road — for the chickens, that is. Mortality composting is the most common way to repurpose dead chickens. This became the case in the 2015 epidemic with the U.S. Department of Agriculture supporting composting as the most environmentally friendly end of life option for the birds. You can read about it here. My quick search found multiple examples of state guidance for how to compost dead chickens. On farm composting is the recommended option (Figure 1) as transporting the carcasses off farm increases the potential for disease to spread. You can layer those dead layers with manure and a high carbon material. Sawdust and straw are two examples. Add water as needed.

The challenge here is that with large scale mortalities, farms may not always have sufficient space or high carbon material to compost. With the latest incidence of bird flu, most did. One farm in Michigan sent two million dead birds to the landfill. Of the 3% of all poultry mortalities that have ended up in landfills rather than the compost pile since 2022, that farm accounted for 66% of them.

Poultry mortality composting during the outbreak of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza. Photo ©2007 Gary Flory

A brief aside: Before you compost the birds they have to be killed. In many cases, fire-fighting foam is used to suffocate the birds and therefore it ends up in the resulting feedstock mix. While the finished compost will be influenza-free if done properly, it is also likely to contain very high concentrations of PFAS.

Landfilling birds is a great way to spread the virus. Vectors like birds and rats think of landfills as an all you can eat smorgasbord. If you think dead raw chicken is appetizing, you will likely think of the HPAI virus as extra seasoning. In other words, mortality composting has taken hold. It is recognized and used as a safe way to repurpose dead birds safely. The organics industry has done its part here and can’t take any credit or blame for the spike in egg prices with this last outbreak of avian flu.

Chicken Feed

That may not be the case with the live birds. Birds eat. Growing chickens for eggs is big business. On a commercial scale, chicken feed is a finely tuned operation where costs are monitored very closely. No homecooked porridge for the flock. Chicken feed accounts for about 60% of the cost of producing eggs. If you can save a penny a day per bird and have a million birds, that adds up. Commercial chicken feed is typically a mixture of corn, soybean meal and oil, distillers’ grain and supplements (Langemeier, 2022). Prices for both corn and soy were both high in 2023. The average cost of feed (based on an index) was 87.3 from 2007-2022. Back in 2021 it went up to 100, meaning keeping chickens fed cost more money. For 2023, the feed index was projected to be at 122.2, well above the running average. That coupled with mortalities from HPA1 certainly impacted egg prices.

To put quantities of birds and feed into perspective let me quote from one source I read: “Each one million laying hens on a farm require approximately 120 tons/day of feed, 7 days per week.” Putting that into a more understandable perspective means that each chicken eats about a quarter-pound (113 grams) of feed each day. In egg terms, it takes about 3 pounds (1.36 kg) of feed to generate a dozen eggs. On a commercial scale, where pennies count, using something to supplement traditional feed can have a cost benefit. Using food scraps as a portion of their diet has the potential to reduce costs for both commercial growers and for us egg eaters.

Mill, the home appliance that grinds and dries your food waste, has opened that option up for people who use their machine and for others. The company went through the rigorous testing and certification process to allow the “meal” from its units to be used as chicken feed for commercial growers. If you have a Mill at home, you can send your dried meal to the company’s facility outside of Seattle where it is scanned for potential contaminants and then sold to a commercial egg producer in the state. If the Mill meal were to be used at a 10% by weight rate of addition, that would mean about 11 g of food scraps per bird per day.

ReFED estimates that we (consumer sector) waste 349 pounds of food per person per year. Even taking the water out of that, you end up with almost a quarter-pound dry per day. Certainly, plenty to spare enough to supplement the diet for a chicken or three. Sending food scraps to chicken farms would provide a high value home for our waste and likely reduce the costs of producing eggs. The fact that chickens are raised commercially in most states in the U.S. means that transport wouldn’t be too expensive or too much of an obstacle. The big obstacle here is the level of behavior change that would be involved. People may gripe about the price of eggs, they may even vote based on the price of eggs. Getting them to not put their food scraps into the trash and instead into an appliance and then sending those to a special address is a big ask. You have to be pretty eggceptional to make that work on a significant scale. This might be a more practical large-scale solution for commercial establishments (stores and restaurants) and food processors.

Backyard Chickens

Backyard chickens are another story. One thing that happened with the human pandemic (the Covid one, hopefully not to be repeated with a human version of the bird flu) is that people started raising their own chickens. Backyard chickens are all the rage. One estimate I found said that about 12 million people are now raising chickens in their back yards. Sending your dehydrated food scraps away in a box is one thing. Taking them to your backyard birds, or even your neighbor’s birds, is a goal that is well within reach.

The neighbor’s chickens (left) get the Mill meal from the author’s bin for which fresh eggs are given in return.

Looking online there is plenty of guidance on how to integrate your food scraps into the meal plan for your birds. Not too much, not anything rotten, no raw eggs (eggs are for your diet, not theirs), but in general food scraps are a great addition to a meal plan for your home chickens. One article I read even suggested that you let your birds graze in your compost pile for an hour or so each day. Going local is what we’ve done with our Mill meal. Our neighbor has chickens. We provide them with the dried food from our Mill as well as fresh garden waste and in exchange we get eggs. For free. In many colors and sizes. With beautiful golden yolks. I didn’t even know that egg prices had gone up because I rarely need to by them. It certainly wasn’t a factor in my voting choices.

Local Eggonomics

Whether you are ecstatic or beside yourself about the outcome of the elections in November, there is a high probability that concerns about climate change and environmental stewardship will not be front and center on a national level for the next few years. This is a great time to start thinking locally. If you work with organics on a large enough scale, tag onto the Mill coattails and think about selling material to commercial poultry farmers. You may not be able to influence national politics but you can have a regional impact on your bottom line and the price of eggs. If you operate on a smaller scale, like your own kitchen and garden, you can still make an impact. Get some birds or make friends with people who have birds. You’ll save on eggs, help the planet and strengthen your community ties. As Tip O’Neill, a former speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives once said, “All politics is local.” Eggs are a good way to start.

Sally Brown, BioCycle Senior Adviser, is a Research Professor at the University of Washington in the College of the Environment.