The number of communities in the U.S. with residential food waste collection service has grown by more than 50 percent since 2009.

Residential food waste collection in the U.S. has grown significantly in the past two years. Since BioCycle’s last survey (December 2009), the number of communities with programs has increased by more than 50 percent. There are now over 150 communities with source separated organics (SSO) programs, spreading across a total of 16 states. While the largest gains were still seen on the West Coast, major headway is being made throughout the U.S.

Some of these are small pilot programs with a few hundred households; others are expansions of existing programs, reaching several hundred thousand households. To qualify for this BioCycle survey, a program must offer curbside collection of residential food waste, even just raw fruits and vegetables.

While each community program described in this report has its own method for residential food waste collection, several trends are apparent. Most communities provide kitchen collectors to each household, and many encourage use of approved compostable bags, to assist with the daily routine of collecting food scraps, and increasing participation rates. Varied rate structures, or pay-as-you-throw (PAYT) schemes, are another method communities with SSO collection use to increase participation, showing residents how to save money by reducing the size of their trash can.

An even more aggressive approach is less-than-weekly trash collection, which appears to be a growing trend as communities try to increase participation rates and divert a higher percentage of organic waste. If trash is collected biweekly, or even monthly, there is a huge incentive to divert all putrescible food wastes into the organics container to avoid being stuck with a smelly trash can for weeks. Peter Anderson, director of the Center for a Competitive Waste Industry, is researching “Less Than Weekly Collection” for EPA Region 9. “Roughly 75 percent of the cost of curbside waste programs is collection, so communities stand to achieve significant savings by reducing trash collection frequency,” says Anderson. “Besides the economic benefit, less-than-weekly collection will get everyone to participate in food waste composting, regardless of their environmental inclination. If we truly want to capture all of the organics that are creating methane in landfills, not just the easy stuff, this is the only way.”

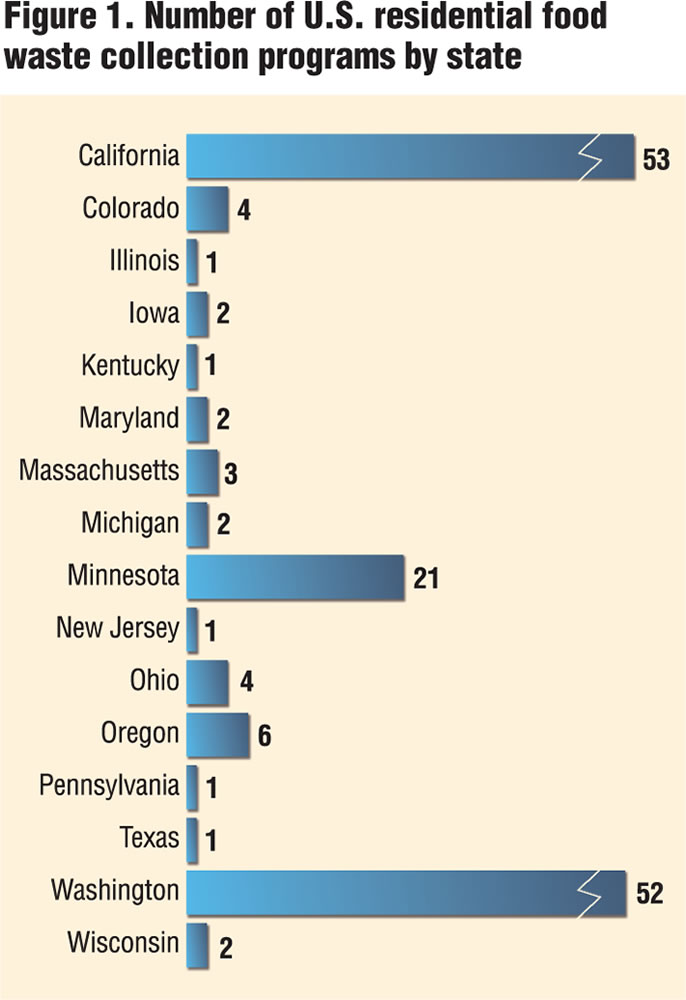

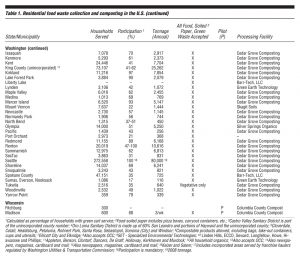

Table 1 lists communities in the U.S. with curbside collection programs for source separated organics. Figure 1 provides a summary of programs by state. The sidebar describes a few residential drop-off programs, and a follow-up article will look at grassroots curbside collection programs across the U.S., where people have started small businesses or cooperatives to collect residential food waste in their cars, pickup trucks or bicycle trailers.

Table 1 lists communities in the U.S. with curbside collection programs for source separated organics. Figure 1 provides a summary of programs by state. The sidebar describes a few residential drop-off programs, and a follow-up article will look at grassroots curbside collection programs across the U.S., where people have started small businesses or cooperatives to collect residential food waste in their cars, pickup trucks or bicycle trailers.

California

Alameda County: Alameda County has been collecting residential food waste since 2002, and currently has 365,000 single-family homes with SSO service. In 2010, a total of 173,914 tons of residential organics were collected, which is a mixture of yard trimmings and food waste. “We estimate that about 5 to 10 percent of that tonnage is food waste,” reports Brian Mathews, Senior Program Manager for StopWaste.Org. All food wastes, including meat, dairy and food-soiled paper, are accepted, with weekly collection of all materials streams (trash, recycling, organics). Compostable bags are allowed in some, but not all, community programs. A variety of outreach techniques are used to boost participation rates, including creative regional media campaigns, bill inserts and contests. Organics are composted at Recology Grover and Newby Island (Allied/Republic).

Arvin, Bakersfield, San Fernando: Arvin’s residential food waste program began in 2006, but does not allow meat (food-soiled paper is okay), as authorized by the county. “We currently have 3,363 households with trash, recycling and organics service,” says Ray Scott of Mountainside Disposal, which has the contract to service Arvin. “We collected 2,210 tons of organics in 2010. About 33 percent of that is food waste, by weight.” Trash and organics are collected weekly, with recycling every other week. Compostable bags on the Biodegradable Products Institute’s approved list (see www.bpiworld.org) are permitted, and organics are taken to Community Recycling’s facility in Lamont for composting.

Bakersfield does allow some vegetative food scraps in its green cart program. San Fernando’s residential food waste program, launched as a pilot in 2002, is no longer operating. “We have shared the data with the city and are evaluating whether a citywide program will be implemented,” says Tim Frey of Crown Disposal, the hauling company servicing San Fernando. “The pilot program was conducted throughout the city and what we found was that it did not yield much in terms of tonnage. Residents in San Fernando do a very good job of consuming and not wasting the food that they prepare. Our experience has been that the commercial food waste programs yield significantly more tons than the residential programs.” The decision to continue the residential program may be revisited at a later date.

Central Contra Costa: The Central Contra Costa Solid Waste Authority (CCCSWA), just north of the San Francisco Bay Area, services about 62,500 households with food waste collection. “We allow all food wastes, mixed with yard trimmings, even grease and sauces,” says Bart Carr, Senior Program Manager at the CCCSWA. “We do walking audits each year, probing the upper 20 to 30 percent of the cart, and found that about 35 to 40 percent of residents place food scraps in the green cart on a weekly basis, although this is likely higher on a monthly basis. We are working with a marketing consultant next year to test different approaches for promoting residential waste diversion.” Residents are given a two-gallon kitchen pail when signing up for service, and are now permitted to use BPI certified compostable bags. All material streams are collected weekly, and depending on the town, organics are either composted at Newby Island or Recology Grover. Multiunit buildings can join the program, but are not currently being targeted.

Los Angeles: The city of Los Angeles launched a residential food waste collection pilot in 2008, which continues to operate with about 8,700 households. “Of all the households, about 70 percent were observed to have green bins,” says Rowena Romano, Environmental Engineer with the city’s Department of Public Works. “About 3,000 tons of organics are collected annually from these households. Based on a waste characterization study in August 2011, the food waste fraction, including food-soiled paper, was about 1.3 percent of the setout material. Contamination was about 6.5 percent.” Los Angeles has a two-tier rate structure, essentially charging extra for larger trash and organics carts (the standard offering is 60 gallons for trash, 90 gallons for recycling and yard trimmings). Kitchen pails were handed out at the start of the program, along with a bilingual “how-to” guide, but compostable bags are not permitted. The organics are composted at Athens’ American Organics in Victorville.

San Francisco: About 90 percent of San Francisco’s 350,000 households now have food waste composting service, a major increase after organics collection became mandatory in 2009. “While it is mandatory that everyone participate, and this impacted single-family households quickly, we are still bringing on new apartment buildings,” reports Jack Macy, Commercial Zero Waste Coordinator for SF Environment. “Recology currently collects about 600 tons/day of organics in San Francisco, or 150,000 tons/year.” The city recently passed a monumental landmark in November 2011, having diverted a total of 1 million tons of organics since the start of the program. About 20 to 40 tons of food waste (mostly commercial) are digested by the East Bay Municipal Utility District (EBMUD), and a new project is expected to increase this amount to 120 tons/day (see “Utility District Ramps Up Food Waste To Energy Program,” November 2011). The remaining organics are composted at Jepsen Prairie Organics. A pilot project is planned for one garbage route to test less than weekly trash collection, to determine how effective it is at increasing participation and diversion numbers. The city is currently at 78 percent diversion (see “Zero Waste On San Francisco’s Horizon,” July 2011).

Recology, the city’s hauler (which also owns the composting facility, MRF and landfill), continues to educate the community about waste diversion, such as through its garbage art program. “About 900 San Franciscans will come down to the dump on a rainy Friday night in January to see an art opening,” says Robert Reed with Recology. They also have innovative ad campaigns, such as collection trucks with 3-D imagery displaying the vehicle’s contents.

San Mateo: The city of San Carlos was the first in San Mateo County to start a residential food waste program in March 2009, but the program went countywide in January 2011, with the start of new contracts with Recology. “Our service area is San Mateo County, and includes 12 Member Agencies: Atherton, Belmont, Burlingame, East Palo Alto, Foster City, Hillsborough, Menlo Park, Redwood City, San Carlos, San Mateo, San Mateo County (unincorporated), and West Bay Sanitary District,” says Monica Devincenzi, Recycling Outreach & Sustainability Manager for RethinkWaste. “We have approximately 92,000 single-family homes, and 100 percent have organics carts. We anticipate we will have collected approximately 74,500 tons of residential organics by the end of 2011.”

All food wastes are allowed, including soiled paper and approved compostable bags. All curbside materials are collected weekly, with a PAYT structure ranging from 20 to 96-gallon carts for garbage. Recology is the franchised hauler, and unloads organics at a municipal transfer station, operated by South Bay Recycling, which then hauls the material to either Recology Grover or Newby Island for composting. “We send approximately half of the material to each composter,” explains Devincenzi. “We opted for contracting with both facilities to ensure that we would have somewhere to send the material if a problem arose with one of the sites.”

Santa Cruz County: Santa Cruz County (unincorporated), as well as Capitola and Scotts Valley, continue to allow residents to place raw fruits and vegetables in their green carts. “The intent is to allow anything that grows in the yard or garden, from lawn clippings to the apples that fall from your tree,” reports Tim Goncharoff, with Santa Cruz County Public Works. “Postconsumer organics are still not accepted in residential green carts. It’s a somewhat hazy dividing line, but it mostly works for us.” Compostable bags are permitted in the program.

Sonoma County: All of Sonoma County (incorporated and unincorporated) has access to curbside yard trimmings service, in which vegetative food waste and incidental soiled paper are permitted. One community, Sebastopol, is allowed to include meat and dairy, because its program was created before regulations were set. A PAYT structure allows residents to reduce trash cart size down to 20 gallons. “In 2010 we collected 96,744 tons of all organics, which includes self haul, commercial and residential,” says Patrick Carter, Waste Management Specialist with Sonoma County Waste Management Agency (SCWMA). “Food waste is estimated at about 1 percent, or 1,000 tons.”

Sonoma Compost Company is the processor at SCWMA’s facility. Compostable bags are not a permitted feedstock, because the compost is certified for use in organic agriculture. “SCWMA is nearing the end of a process to examine a new location for a compost facility, which would nearly double our capacity and allow for all food wastes,” notes Carter. “Also, Sonoma Vermiculture is transitioning from a pilot project to commercial scale food waste vermicomposting. In the next year or two, their goal is to have a facility that can accept nearly 100 tons/day of all food waste, including meat and dairy wastes.”

Stockton: Starting in 2003, Stockton began allowing residents to include food waste in their green carts. About 76,000 households currently have food waste collection, with 43,000 to 44,000 tons of organics diverted in 2010. All food wastes, including meat and soiled paper, are accepted, but not compostable bags, as dictated by the composting facilities (due to inability to differentiate between compostable and conventional in the loads being tipped). A PAYT scheme allows residents to reduce their garbage cart size to 20 gallons. Two different haulers service the city, Waste Management (WM) and Republic, with WM delivering organics to the city of Modesto’s municipal facility, and Republic utilizing its own site (Forward, Inc.). “Other programs in the area allow fruits and vegetables in the green cart, as part of the definition of green waste, but are not specifically permitted to take food waste,” says Thom Sanchez of WM. “We have 50 cities in our territory, all the way up to the Oregon border, and northern Nevada, and almost nobody’s talking about residential food waste, just commercial. First, there aren’t many permitted sites in our area to take food waste. Second, residential food waste is a smaller portion of total recovery for most communities, compared to commercial.”

Colorado

Boulder and Louisville: The cities of Boulder and Louisville, as well as unincorporated Boulder County, are up to about 33,000 households with food waste collection. The city of Boulder went citywide in 2008, and has 19,014 single-family garbage accounts, all of which are required to include organics and recycling collection. Boulder also has 63 multiunit properties participating, for which the city provides a rebate to the hauler to make it more cost-effective, due to Colorado’s extremely low landfill tip fees. A pilot is being planned to increase participation of more multifamily units. Boulder does not permit meat, due to the prevalence of bears, whereas Louisville and Boulder County do allow it.

The combined residential organics tonnage collected from the three areas for 2010 was around 7,300 tons. Organics collection is biweekly, and there is a PAYT structure as an incentive for participation. Kitchen pails are not distributed. Residents can put organics directly into the curbside cart, although use of certified compostable bags are promoted as a means of increasing participation. “However, with our open windrows the light material comes to the sides and doesn’t break down, so we’ve purchased a vacuum system for removing any remaining film after the compost comes out of our trommel screen,” says Bryce Isaacson of Western Disposal, which hauls and composts most of the organics for the area.

Denver: Denver launched a residential food waste pilot in 2008, and the program was continued for two years through grant funding. “In 2010 we hit the point where funding to keep the program running dried up, and we informed the 3,000 or so participants that it was shutting down,” reports Charlotte Pitt, Interim Manger of Denver Recycles/Solid Waste Management. “There was an outcry from the community, so we decided to keep the program running, charging a fee directly to residents for the service.” Trash and recycling are paid for through the city’s general fund. The number of participants dropped to about 2,300. About 1,000 tons of organics were collected in 2010, and composted by A-1 Organics.

“We elected a new Mayor in July, and composting was talked about on the campaign trail,” says Pitt. “A financial task force will make recommendations to the Mayor to address budget problems, and charging for trash may be on the agenda. Our struggle so far has been making the economics of waste diversion work, with low landfill tip fees and no state mandate for landfill diversion, but we’ve done a good job with recycling, all considered.” Food-soiled paper was formerly included in the organics cart, but this changed starting in early 2012, and it is now included in the recycling stream instead.

Illinois

Barrington: The first residential food waste pilot in Illinois was conducted in 2010, in the city of Barrington. “Our state legislation changed in 2010, allowing for the pilot,” says Mary Allen, Recycling and Education Director at the Solid Waste Association of Northern Cook County (SWANCC), which was responsible for running the pilot. “Food waste composting infrastructure is still in its infancy, and the costs of diversion are still high. Our agency is comprised of 23 suburbs, with about 230,000 households, located just north of Chicago.” A homeowner association in Barrington with 300 households was chosen for the pilot, as they already had 96-gallon yard trimmings carts. Kitchen collectors and compostable bags were given to residents in May 2010, with the pilot concluding in December 2010, when seasonal yard trimmings collection ended. At first the organics collected were taken to the Land and Lakes composting facility on the south side of Chicago, but the distance prevented SWANCC from moving beyond the pilot project, due to efficiency and cost-effectiveness. Towards the end of the pilot, a composting facility closer by in Wauconda (Mid-West Organics) received a permit for food waste.

“About 25 to 30 percent of residents participated, with reasons for not supporting the program ranging from wanting to continue backyard composting, to those who felt they didn’t produce enough waste to participate,” continues Allen. “While we allowed meat, fish and dairy, we didn’t allow soiled-paper, which in retrospect was a mistake because it limited our diversion potential, and the paper cups and plates that could’ve been included are actually not recyclable in our community. On average, we collected 1.9 pounds of food scraps per household each week, which is quite low.” SWANCC is writing a strategic plan for 2015, and organics will be part of the equation. With more facilities in the region permitted to take large quantities of food waste, including commercial and institutional, the economics of a residential program will become more feasible for the suburban community.

Iowa

Cedar Rapids: Cedar Rapids added 400 households to its green cart program, which permits fruits and vegetables, and is now servicing a total of 38,900 customers. “This increase is a combination of condos and single family homes,” says Mark Jones, Superintendent of Cedar Rapids Solid Waste and Recycling Division. In 2011 the city collected 14,325 tons of organics, mostly yard trimmings. (Its composting facility is only permitted to receive 2 tons/week of food waste.) “We are delivering 35-gallon garbage carts, moving away from manual collection toward semiautomated,” continues Jones. “When handing out the cart, we also give residents a booklet explaining the curbside programs, which has resulted in more phone calls requesting larger recycling carts, and more participation with green carts.”

In 2009 the city hired a community education coordinator, whose responsibilities include tracking programs across the U.S. to learn what can be applied to Cedar Rapids. “Zero waste goals are tremendous, but they need a lot of support,” Jones explains. “We started to bring in large amounts of food waste from grocery stores, and tried simply mixing it into our yard trimmings piles. We ran into some problems, stopped, and are now proceeding again more cautiously. Once we get the recipe right, with fewer odors, and succeed with a positive experience, then we’ll likely ask Iowa DNR to expand our permit for more volume. At that time we might allow additional food scraps from homes.”

Dubuque: The city of Dubuque continues to offer a limited number of food waste subscriptions, currently at 230 households, due to permit restrictions that only allow 2 tons/week of food waste at the composting facility (like Cedar Rapids). Participants are given a 13-gallon curbside container, and a 2-gallon kitchen pail, and diverted 80 tons of food waste and soiled paper in 2010. All material streams are collected weekly, and the city has a PAYT program. According to a June 2010 waste sort, almost 30 percent of the current materials set out as refuse from the average Dubuque household could be processed into compost, which is equivalent to 3,000 tons/year.

Kentucky

Lexington: The city of Lexington launched a residential food waste pilot in 2011, reaching about 400 households. “These homes may place food waste in their 95-gallon yard waste collection cart,” says Esther Moberly, with the city of Lexington. “There are also four businesses and three schools participating in the pilot.” All food wastes, including meat and soiled paper, are accepted, collected weekly and composted at the city’s facility. Outreach for the pilot includes a website, presentations, fliers, door hangers, mailers, etc. “We are preparing a DVD on how to collect and separate at home, and what happens after it is collected,” notes Moberly. “We accept ASTM certified compostable bags and utensils, and offer information on where to purchase them. So far we haven’t had much trouble with contamination from the food waste collection, although we’ve had problems with people outside of the pilot placing yard trimmings in plastic bags.”

Maryland

Howard County: Howard County conducted a small pilot project in 2010 with 33 households, and expanded the program in 2011. “We now offer the program to 5,000 households, and about 1,000 have signed up,” says Alan Wilcom, Chief of Howard County’s Recycling Division. “We delivered 35-gallon carts in September 2011, but didn’t give out kitchen pails. During the small pilot households were given kitchen pails, but most reported using their own.” About 4,200 pounds/week of organics are currently collected, or about 8.5 pounds/household/week. Meat, fish, bones and compostable bags are not currently permitted, as dictated by the composting facility, Recycled Green Industries. “We have plans to build our own site to handle a wider range of materials, probably using aerated static piles,” continues Wilcom. “Not allowing meat significantly limits the amount of tonnage we can divert.”

The reason for starting a residential food waste program was twofold: reduce the nutrient load of sending food scraps down kitchen sink disposers, which was burdening the wastewater treatment plant; and increase the recycling rate (currently at about 47 percent), with food waste being the logical target. The county still promotes backyard composting and grasscycling, especially in communities with large lots, and has given away thousands of free backyard composting bins.

Massachusetts

Hamilton: A small residential food waste pilot project was conducted in Hamilton in 2008 to determine the feasibility and interest of residents. A decision was recently made to launch a citywide program that will encompass the sister city of Wenham. “We hope to have the program full-scale by late February or March 2012, with opportunities for about 2,400 households in Hamilton and 1,200 in Wenham,” reports John Tomasz, Superintendent of Hamilton Pubic Works. Currently, 448 households are participating in Hamilton, and 187 in Wenham. “Right now we are collecting approximately 130 tons/year for both towns,” continues Tomasz. “We hope to initially divert at least 200 to 250 tons once we go full-scale with a goal of over 500 tons.” The impetus for going citywide is the anticipated cost savings: approximately $20/ton, and the belief that at some point organics recycling will be mandatory. BPI-approved compostable bags are permitted, with the organics composted at Brick Ends Farm. (For more information on Hamilton and Wenham’s new program, see “Residential Food Waste Collection Rolls Out,” December 2011.)

Ipswich: In November 2011 the city of Ipswich launched a year-long pilot, which it hopes to extend if the feedback is positive. “We currently have about 120 households participating, but this will continue to grow,” says Judy Sedgewick, Recycling Coordinator for Ipswich. “The city has over 4,000 households receiving trash service, however the challenge is that our town is quite large land wise. We have had to limit the collection to certain parts of town so far, because driving the truck all over town to collect the food waste is expensive. We started by targeting the more densely populated areas.” The city estimates diversion will be roughly 10 pounds/household/week, and is sending the organics to Brick Ends Farm for composting. Ipswich currently has a recycling rate of 37 percent, and hopes the organics program will push this higher. For the pilot, residents are provided with free curbside containers and kitchen pails, and are not allowed to use compostable bags.

Michigan

Ann Arbor: The city of Ann Arbor currently has 13,700 households out of 24,000 subscribed for yard trimmings and food waste collection. This has grown since the program was launched in 2009, due to promotions for the program in 2010. Residents must purchase the cart, and then the service is covered by taxes that pay for garbage collection. While the residential program still only permits raw vegetative food waste, some other facets have changed. “Most notably, we’ve privatized the composting operation to realize significant savings to the city,” says Tom McMurtrie, solid waste coordinator. “WeCare Organics now operates the composting facility, which is still owned by Ann Arbor, and they are actively looking to expand organics throughput.” Only about 30 businesses participate in the commercial food waste program, and the city is looking to get another dozen on board this year.

The other change has to do with collection of leaves, which used to be picked up loose on the street in the fall. Now residents are required to put them out as part of the curbside program. This has encouraged more residents to compost at home and grasscycle, resulting in a reduction of the volume collected. Organics collection continues to be seasonal, from April through December, as yard trimmings make up most of the tonnage. Ann Arbor is at about 50 percent diversion, and is in the process of revising its solid waste management plan.

Mackinac Island: The organics collection program on Mackinac Island began in 1992, and utilizes horse-drawn trailers, as the historic island doesn’t allow motor vehicles. Organics are collected in compostable bags, which are then opened and sorted at the composting facility. “Our compost numbers have gone up, because we had a really good year in 2011,” says Paul Wandrie, Composting Facility Manager at Mackinac Island. Diversion numbers have not been calculated yet for 2010, but in previous years 635 tons of food waste were collected, along with 500 tons of yard trimmings and 4,500 tons of manure. The public works department studied the feasibility of anaerobic digestion for the island in 2011, but decided the capital costs were too high to pursue at this point.

Minnesota

Carver County: The current composting site at the Minnesota Landscape Arboretum opened September 1, 2011, and is operated by Specialized Environmental Technologies (SET). The two-acre Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) demonstration project site receives residential food waste cocollected with yard trimmings, as well as food waste from the arboretum’s cafeteria. To avoid the odor issues that resulted in closure of the previous composting operation at the arboretum, this site is located 1,800 feet from its nearest neighbor, rather than the 250 feet at the old site. Reduced annual capacity, and increased daily processing requirements, also help minimize possible nuisances.

In 2010, Carver County diverted 110 tons of residential organics (mix of food and yard trimmings) and 148 tons of commercial food waste. The county is updating its Master Plan, which will focus on increased organics diversion as a method to meet state solid waste and recycling goals. Randy’s Sanitation, one of the area haulers, is piloting a new collection system to reduce the number of trucks on the road. Residents place food waste and soiled-paper in blue compostable bags, which are then collected with the garbage, sorted out at the garbage transfer facility, and brought to the arboretum for composting.

The MPCA is redrafting its rules governing siting, design and operation of composting facilities, with the desired outcome of adding tiers for source separated organics composting facilities that would be less stringent than a MSW composting facility and slightly more stringent than a yard trimmings composting facility.

Hennepin County: Communities in Hennepin began composting residential food waste in 2005 (in Wayzata), and programs continue to be strong, albeit with minimal growth. The city of Shorewood is planning a pilot project for 500 households in 2012, and Minneapolis still has pilot projects in several neighborhoods. “Service is offered on a subscription basis, which makes it difficult to promote, and difficult to track developments,” says John Jaimez, with Hennepin County Department of Environmental Services. “Minneapolis is trying to have a program offered citywide by January 2013, which is when the state’s compostable bag ordinance applies to the city [requiring yard trimmings bags to pass ASTM tests], so they plan on having curbside carts distributed by then.”

Perhaps the biggest change is in state legislation, which added organics to the definition of recyclable materials. “They were previously included with the definition of municipal solid waste (MSW), which caused problems, as it was difficult for cities to organize the separate collection of food waste,” explains Jaimez. “It was about an 18-month process to organize and approve separate collection, but there is an exemption for recyclables, so by adding food waste to the definition of recyclables, it will be much easier and quicker for a city to organize a program. In the next couple years, we expect to see more cities move forward.” Separated organics are composted by SET.

Hutchinson: The city of Hutchinson’s program continues to serve about 6,000 households. “We are working on town homes and apartments now, looking at what it would take to get them involved with residential food waste collection,” reports Doug Johnson, Manager of CreekSide, the city of Hutchinson’s composting facility. “There is a growing competition for feedstocks, as our landfill started generating electricity from their methane. Five years ago when we started, it was easy, but now there are more variables.”

Hutchinson still provides compostable bags to residents at no cost, which has contributed to its high participation and low contamination rates. Since the introduction of the organics program, residents have been given the option of biweekly garbage collection. “At the start of the program, about 50 percent of households switched from a 96 to 30-gallon trash cart, and went with biweekly collection, saving them about $20/month,” explains Johnson. “More and more have opted for this over the years.” They city is diverting about 75 percent of its waste, with organics making up 48 to 50 percent of that diversion, and recyclables 25 percent.

Swift County: Swift County began offering residents the option of residential food waste collection back in 2000, reaching eight towns and some rural areas. “Not much has changed in our program recently,” says Scott Collins, Director of Swift County Environmental Services. “It’s running like clockwork.” About 3,800 out of the county’s 4,300 households participate. Organics are composted at the Swift County municipal composting facility. Finished compost is given away to farmers and residents.

New Jersey

Princeton: In June 2011 Princeton started a pilot project, and has more than 220 homes subscribed. “Originally the pilot was supposed to end in August 2011, but we were so pleased with results that we decided to keep it going as a permanent program,” says Janet Pellichero, Princeton’s Recycling Coordinator. “People are shocked at how much their garbage is reduced, and are now making wiser purchases.” Schools and businesses are joining the program too, as news of the program travels via word of mouth.

The city organized the pilot with local hauler Premier Food Waste Recycling, which charges $20/month for organics only collection, or $25/month for organics and trash service, with a 32-gallon organics container and 64-gallon trash container. A two-gallon kitchen pail and supply of compostable bags were provided to residents, along with literature on how to participate. All food wastes are permitted, including fats, oils, grease, waxed cardboard, etc. Organics are hauled to the Wilmington Organics Recycling Center (WORC) in Delaware. Organics and trash are collected weekly, with recycling biweekly. “Mercer County tipping fees are really high, close to $125/ton, which is a driving force for the program,” notes Pellichero. “Because we are a subscription based town, the municipality isn’t getting this savings, the residents are. Average monthly waste costs without organics collection are $55 to $60, so we are hoping to see more and more subscriptions to the organics program.”

Ohio

Fairborn and Miami Township: Waste Management offers SSO service in two communities, Fairborn and Miami Township. About 1,000 out of 10,000 households in Miami Township subscribe to organics collection, and about 4,000 out of 60,000 subscribe in Fairborn. All streams are collected weekly, with organics composted by Paygro, which does not currently allow compostable bags.

Huron: The City of Huron began offering SSO in 2009, adding food waste to the yard trimmings subscription, and extending service year round. There are 1,569 subscribers, out of the 3,378 households with trash service. Barnes Nursery collects the organics, about 851 tons/year, and composts them at its nearby facility. Residents must provide their own curbside carts and kitchen collectors. While compostable bags are permitted, they are not promoted in brochures, due to possible confusion with conventional bags.

Luckey: Luckey began a residential food waste program in October 2009, replacing its poorly performing recycling program with SSO. Recyclable paper (e.g., newspapers, magazines, cardboard and junk mail) are accepted in the organics cart. NAT Transportation collects SSO from 201 out of 411 households, delivering the material to Hirzel Farms for composting. About 75.5 tons were collected in 2010. Bottles and cans are now collected monthly, with organics and trash still collected weekly.

Oregon

Corvallis: The city of Corvallis began allowing vegetative food waste in its residential green carts in 2009, and expanded to all food waste (including meat) in 2010. Service is available to 12,643 residential customers, of which 11,476 are currently subscribed. Organics and recycling are collected weekly, and there are several options for garbage collection, with aggressive PAYT (frequency ranges from on-call to weekly, with carts ranging from 20 to 90 gallons). In 2010 Allied (Republic Services) collected 9,310 tons of organics, composted at its Pacific Region Compost (PRC) facility. PRC doesn’t currently allow compostable bags from Corvallis, due to problems identifying compostable versus conventional plastics. While organics service is offered to multiunits, the focus of the program right now is on single-family homes, schools, restaurants and universities.

Marion County: Marion County rolled out a residential food waste program in July 2010. “Our program reaches roughly 54,031 households in the cities of Salem and Keizer, as well as part of West Salem, which is actually outside of the Marion County boundary,” says Sarah Keirns, Marion County Waste Reduction Coordinator. All food wastes are allowed, including soiled paper, but not compostable bags, as requested by Pacific Region Compost. Residents were given a two-gallon kitchen pail to help improve participation. Salem has weekly collection of all waste streams, whereas Keizer collects organics and recycling biweekly. Both communities have a PAYT plan, going down to a 20-gallon trash container. “We run newspaper ads to promote the program, as well as videos, commercials on public TV, promotion at events, etc.”

Portland: The city of Portland conducted a yearlong residential food waste pilot with 2,000 households starting in 2010. At the end of October 2011, they launched the program citywide, reaching 143,000 single-family households. “Judging by our waste audits, about 25 to 30 percent of residential waste in Portland is organics and could be diverted through the program,” says Arianne Sperry, with the city of Portland’s Bureau of Planning & Sustainability. “In 2007, Portland’s city council adopted a goal of 75 percent diversion by 2015, and the current rate is 67 percent, and we’re hoping that organics will be the next frontier. Over 700 businesses currently participate in the commercial organics program, and we will make a push for more businesses this year. Commercial waste accounts for 75 percent of the total garbage generated in city.”

During the pilot, 87 percent of residents liked the program, which gave the city confidence in implementing it full-scale. All types of food waste are permitted, along with nonrecyclable soiled paper. Compostable bags are allowed, but not compostable cutlery or takeout containers. “During the pilot our organics were going to Cedar Grove, so we followed their [compostable product] guidelines,” continues Sperry. “However, now the organics go to Pacific Region Compost and Nature’s Need (Recology), and we all want to be conservative at first, since it will be easier to add items later instead of taking them out. There’s already a lot of confusing information for residents to sort through at this point.” Residents are given a two-gallon kitchen pail.

While several smaller cities have the option of biweekly trash collection, paired with a food waste program, Portland is the first large city in the U.S. to implement this on a citywide scale. “During the pilot residents had biweekly trash collection and weekly food waste collection, and that’s what we’ve rolled out for the entire city now,” Sperry says. “There’s also options for once a month trash collection, and just on-call trash collection. We are trying to get people to think of it as materials management.” An anaerobic digestion facility is being planned by Columbia Biogas to process some of the city’s food waste.

Pennsylvania

State College: A residential food waste pilot project was started in the borough of State College in 2010, and is ongoing, with about 587 households participating. “There are plans to go borough-wide, if the results of the pilot are favorable,” says Joanne Shafer, Deputy Director/Recycling Coordinator for Centre County Solid Waste Authority. “If that happens, it will be phased in, incorporating more commercial properties before including additional single-family households.” Organics are collected weekly and composted by the Borough of State College, which allows soiled paper in the program but not meat (there are plans to allow meat in the future). The county’s diversion rate is approximately 52 percent, with a goal of zero waste to landfill in 40 years.

Texas

San Antonio: In September 2011, the city of San Antonio rolled out a large-scale pilot project, reaching 30,000 households. “We have 340,000 collection points, so wanted the pilot project to be substantial,” says Josephine Valencia, Assistant Director of San Antonio’s Solid Waste Management. “We just finished rollout of automated blue and brown carts in the last two years, and it was a difficult transition with mixed feedback. We have strong individualism in Texas, so we communicate that residents are not mandated to participate in the food waste pilot, but it’s an option.” Specific neighborhoods were targeted for the pilot that are reflective of the larger demographic, looking at education, income, recycling rate, etc. “We want a realistic picture of what can be expected with citywide expansion of the program,” notes Valencia. So far, waste diversion goals are driving the program, not economics, because landfill and composting tip fees are about the same. They city may be able to negotiate lower composting tip fees in the future, once the program is full-scale.

The organics are being processed by New Earth (see “Composting Integrated Into Family Business,” October 2009), which wants to start out cautiously with residential food waste. “Soiled paper is fine, but only small amounts of meat scraps, and no compostable bags yet,” explains Valencia. “With the blue cart program, we are at 24 percent diversion, but in June 2010 we adopted a 10-year solid waste plan, with a goal of 60 percent by 2020. This program will get us on our way towards that goal.”

Washington

Bellingham: About 7,040 households are subscribed to food waste collection in the Bellingham area, which includes the smaller cities of Blaine and Ferndale. About 60 multiunit buildings have service, along with 250 housing units on the campus of Western Washington University. About 4,000 tons of residential organics were collected in 2010, of which 15 percent is estimated to be food waste. All food wastes are permitted, including meat, soiled paper and BPI-approved compostable bags. “We supply a list of approved compostable bags,” notes Rodd Pemble, Recycling Manager for Sanitary Service Company Inc., which services the Bellingham area. “Our standard curbside program is 20 years old, so customers who sign up for FoodPlus! composting service are used to properly sorting materials and minimizing contamination.”

An aggressive pay-as-you-throw (PAYT) program is in place. The standard trash collection is a 60-gallon container picked up biweekly, but can be reduced to 30-gallons picked up monthly. Organics are composted at Green Earth Technology in Lynden, which uses the GORE Cover system.

King County: King County has 308,436 single-family households with garbage collection, and roughly 63 percent subscribe to organics collection service. Some cities in King County offer this service to multifamily complexes, but that data is not currently available. In 2010, 143,782 tons of residential organics were collected. “We estimate that about seven percent of the organics collected are food waste, based on a 2009 countywide sampling,” says Bill Reed with the King County Solid Waste Division. “As of 2009, we were at about 48 percent diversion rate for residents and businesses, with goals set at 55 percent by 2015 and 70 percent by 2020.”

All communities have PAYT rates, although most have biweekly recycling collection, and about half have biweekly organics collection. The city of Renton is the only community in King County to offer biweekly trash collection. Organics are composted at Cedar Grove’s facilities in Maple Valley and Everett. “To promote organics diversion, King County maintains website information, and does radio, print and TV ads serving all cities in area,” notes Reed. “We also coordinate with haulers to provide mailers and print ads in unincorporated areas, and we do neighborhood challenges to increase diversion, retail partnerships, and community events. Cities may also do their own outreach.”

Seattle: All Seattle households with curbside cart garbage service are required to either have organics collection or apply for an exemption, stating they are composting in a backyard. “For households on garbage dumpster service [typically apartments], we have a new requirement that, beginning September 2011, they are required to provide organics collection, unless they are exempted due to space limitations,” says Brett Stav with the City of Seattle. There are 146,000 single-family households, and about 5 percent are exempted from organics carts due to backyard composting. For multifamily, there are 5,400 buildings, which represent about 126,593 households; only 25 buildings are exempt due to space constraints. “We also offer multifamily properties a one-time $100 utility bill discount for signing up for organics service,” notes Stav.

Seattle’s 2010 recycling rate is 53.7 percent, with a goal of reaching 60 percent by the end of 2012. All curbside materials are collected weekly, with a PAYT system. Besides the standard mailers, surveys and ads, Seattle is working with Cedar Grove, compostable bag manufacturers and local retailers to provide discounts (“rewards”) for participating. In 2012, Seattle is considering a pilot project to explore the feasibility of biweekly trash collection.

Thurston County: Thurston County’s residential food waste program began in 2008, and includes Olympia, the state capital. Not including Olympia, there are 53,593 residential garbage customers, of which 15,309 subscribe to organics collection. Olympia has 14,000 households, 51 percent of which are subscribed to organics collection. “Nearly every Thurston County resident has access to organics collection,” says Emily Orme, Education and Outreach Specialist for Thurston County Solid Waste. “There are only a few very small isolated pockets of the county that do not have access. A 2009 waste composition study we conducted indicated that about 23 percent of our total residential waste stream was still food waste.”

Waste Connections is the hauler for Thurston County, and owns Silver Springs Organics, where it composts the collected food waste. In 2010, 5,250 tons of organics were collected from Olympia residents, plus another 11,060 tons from the rest of Thurston County. The organics program is promoted through several outlets, such as public events, local media, and a semiannual newsletter called “Talkin’ Trash.” Residents place food waste in their green waste collection carts.

In Olympia, trash, recycling and organics are all collected biweekly. All food wastes and soiled paper are permitted, including compostable bags. “Our city waste trucks tip organics at the county transfer station, and then it is hauled to Silver Springs Organics,” notes Ron Jones, Senior Program Specialist with the city of Olympia. “The facility is undergoing renovations and changed its accepted material list in July 2011. It now limits which BPI approved bags it will take, and stopped taking all polycoated cartons and papers, such as frozen food packaging.”

Wisconsin

Fitchburg: The city of Fitchburg recently approved a pilot for 300 households, which will start in April 2012. “The impetus for the pilot was a waste sort that we conducted on 40 homes, looking at trash and recyclables,” says Rick Eilertson, Environmental Engineer with the city of Fitchburg. “The biggest category remaining in the trash was organics, including food waste, soiled paper, pet waste, etc., which accounted for 40 percent by weight. We are currently at about a 32 percent recycling rate, but the waste sort showed a potential of 87 percent through recycling and composting.”

Fitchburg is partnering with Madison’s pilot (see below), adding its homes to their collection route to cut down on hauling costs. Fitchburg currently collects yard trimmings four times per year bagged, and six times loose on the curb, but will be adding a 35-gallon cart for the pilot. “We are still working out the details but will likely accept all food wastes, as well as pet waste,” notes Eilertson. “We’d like to get as much of the organics out of the waste stream as possible, with the idea of eventually collecting trash biweekly.” Compostable bags and kitchen pails have already been donated for the pilot.

Madison: The city of Madison launched a residential food waste pilot for 500 households in April 2011. Residents were given a 35-gallon curbside cart. Households in the program were divided into two groups, half of which received a standard solid kitchen pail, and half received a vented pail along with a yearly supply of breathable compostable bags. A series of surveys are being given to residents for feedback on the two different kitchen pails (for more information on the vented pail system, read “Intensive Source Separated Organics,” April 2010).

During the pilot, all food wastes are permitted, as well as pet waste and disposable diapers. “We want to get as much of the putrescible organics out of the waste stream as possible, so that we can eventually go to less than weekly trash collection,” says George Dreckman, Recycling Coordinator for the city of Madison. During the pilot project organics are being composted at Columbia County’s mixed MSW facility, which cocomposts MSW with biosolids, and therefore is able to handle the plastic contamination of the disposable diapers, screening them out at the end of the process. The city plans on adding more garbage routes to the pilot project each year, and hopes to have its own facility by the time collection is citywide. “The city of Madison and Dane County are considering several options, from simple aerobic composting to a municipally owned anaerobic digestion facility,” continues Dreckman. “A county-owned AD facility could potentially serve several communities.”

Rhodes Yepsen is a freelance environmental writer and was recently hired as Marketing Manager for Novamont North America; organicsdiversion@gmail.com and rhodes.yepsen@novamont.com (respectively).

Food Waste Drop-Off Programs

Several communities around the U.S. have developed residential food waste drop-off programs. These provide a low-cost alternative to curbside collection, and have proven to be quite effective. For instance, the Lower East Side Ecology Center in New York City started a community compost program in 1990, expanding in 1994 to the Union Square Greenmarket four days a week, where it collects several hundred tons/year of vegetative food scraps. In Cambridge, Massachusetts, residents can bring food scraps to two drop-off sites, one at the municipal recycling center and the other at a Whole Foods supermarket.

Chittenden Solid Waste, Vermont: The Chittenden Solid Waste District (CSWD), which serves Burlington and surrounding communities, began a food waste drop-off program in 2001, and currently has eight drop-off sites around the county that residents and small businesses can use free of charge. “We also have two small haulers, one that uses bicycles, which offer residential and small business curbside collection in Burlington for a fee,” says Nancy Plunkett, Waste Reduction Manger for CSWD. “We conducted a residential curbside food waste pilot in 2000, and we will be looking at this again in 2012, with research on the environmental and economic costs of providing county-wide or metro area residential curbside collection.” Currently, three large private haulers offer collection of commercial organics, which are composted at Green Mountain Compost (formerly Intervale), located in Williston.

Windham, Vermont: Windham Solid Waste Management District (WSWMD), in the Brattleboro area, expanded its residential food waste drop-off program, and now has two sites. About 37,000 residents spread out over 17 towns have access to the sites, with the 4-cy containers picked up weekly and the organics composted at Martins’ Farm. “We are seeking additional funding to expand the program regionally, and are looking to process it at a WSWMD facility,” says Cindy Sterling Clark, Program Director for the district. “In April 2012 we will know more about the funding application, and whether our Board of Supervisors is willing to invest in setting up a compost operation at WSWMD.”

WLSSD, Minnesota: Western Lake Superior Sanitary District continues to have a strong residential drop-off program, operating five sites. “Most of the sites use 2-cy poly dumpsters for collection, but two of them use smaller 95-gallon containers,” says Susan Darley-Hill, Environmental Program Coordinator for WLSSD. Winter temperatures allow for a reduction in collection frequency, but most sites are serviced weekly during the warmest months to mitigate odor and vector problems. Sites receive varying amounts of food residuals, averaging 200 to 800 pounds per week. Contamination remains extremely low; the main contaminant is noncompostable plastic bags used to contain food waste.

“WLSSD continues to hand out free compostable bags to drop site users in exchange for their incoming food waste,” notes Darley-Hill, which helps reduce this contamination. “The drop site program addresses concerns unique to the Duluth area: a city with steep terrain, 5 miles wide and nearly 40 miles long, with an open-hauling system of 4 primary haulers. The drop site program was established to provide opportunities for organics recycling for all residents, while minimizing driving distance and excessive truck traffic on aged, hard-to-maintain roads.” The WLSSD composting facility receives, on average, 50 to 60 tons/week of food waste, which includes all of the drop sites and approximately 150 businesses and institutions.

Click here for a pdf file of this article, complete with tables and charts