Top: Unharvested squash in a farm field presents a gleaning opportunity. Photo by Dr. Lisa Johnson, courtesy of the Society of St. Andrew

Jeannie Hunter, Thomas O’Donnell and Kim Charick

Growers and gleaners are essential partners in gathering unharvested farm produce and delivering it to nearby hunger relief organizations. Increasingly, gleaning organizations are also beginning to measure the amount of produce that is left unharvested, helping farmers identify new ways to plant and harvest in order to maximize what they grow, share, and sell. Evidence continues to show that farmers generally underestimate how much food they did not harvest, so real data is helpful to them.

The Society of St. Andrew (SoSA) is the nation’s oldest and geographically largest gleaning organization, operating in 17 to 22 states annually. Since 1983, SoSA has rescued more than 4 billion servings of produce from farm fields and packinghouses that would otherwise have gone to waste. With the help of a U.S. EPA grant, SoSA added the step of measurement into its gleaning practice. This article describes SoSA’s work arranging gleaning events and executing measurements during those events, and offers guidance for others who wish to glean and/or measure. (For the report of amounts gleaned during the period of the grant, see O’Donnell, et al., 2024).

Contacting the Grower

Volunteer training includes harvesting techniques and food safety protocols. Photo courtesy of 2020 Gleaning Census

If you’ve never spoken to a farmer about gleaning before, the first conversation is the toughest. (Remember, the worst the grower can say is no.) There will likely be questions about confidentiality and lawsuits, as well as the denial that there’s much left behind in the first place. Some issues expressed by growers are: 1) Liability for gleaner safety and repairs to any damaged property; 2) Potential loss of privacy; 3) Reputational harm by association with “secondhand” gleaned produce; 4) Time commitment; and 5) Product food safety from harvest to distribution. As for lawsuits, SoSA has protections for accidents on the farmers’ properties in its insurance. Volunteers sign waivers releasing both SoSA and the farmer from liability. Consider that for your gleaning organization. No one can be sued for illness caused by food donations since The Good Samaritan Act of 1996 passed, preventing those kinds of suits.

Some key tips for the first call to a grower that has not allowed gleaning previously include:

- Use the word “loss” and not “waste.” Waste has moral connotations that most of us try to avoid. Loss acknowledges that is it a financial loss for them.

- Keep the data anonymous. Tell them that, and then do it.

- Contamination prevention. SoSA field supervisors are trained in field and food safety measures. Because the gathered food is going to the most vulnerable people in a community, it is especially important to prevent contamination.

- Likelihood of loss in field. If growers are harvesting by hand and not machine, it’s almost certain there’s loss in the fields. If they deny any loss, explain you need that kind of information, too. It’s important to know the good, the bad, and the ugly.

- Emphasize gleaning benefits. Explain why it’s good for them to have you glean. They put lots of effort into growing this stuff! Don’t they want someone to eat it? (This is one place where “waste” may be appropriate — “don’t you hate for all that hard work to go to waste?!”) Make sure growers know donations can become tax deductions. And remind them about field hygiene — fewer fruits/vegetables rotting in the fields means fewer pests the rest of this season and next.

- Discuss the possibility of payment at a fair price for the produce. Don’t be shy on this matter if it is a possibility. Recipients of the produce may themselves want to pay the farmer some amount for the food and transportation. The new 2023 Food Donation Improvement Act extends liability protection when costs are shared for harvesting, handling, and distributing donated food.

- Inquire if the grower has a favorite food pantry nearby. If they know the recipients, they might feel more inclined to give.

Don’t push for a commitment on the first call. The second call will be to set a date and time for a gleaning. Ask when they’re harvesting, and when they’ll be replanting the field if they’ll plow, etc. That informs how much time you have, and hopefully that synchs with dates and times that work with your volunteers and the agencies that will receive the food. Try to put something on the calendar in that second call. Thank them profusely.

The third call will be the day before the event, nailing down details like where to park and where to meet the farmer and some chatting about the weather. It helps to share your excitement about the local food pantry that’s going to receive the food. And offer gratitude as often as possible. Ask now for any details about working on the farm and properly harvesting the crops so no damage is done. In one instance the farmer told us to stay clear of the red rooster because he is a grumpy one.

When working with farmers who have hosted gleanings in the past, all the explanation won’t be necessary. But still plan on three calls — inquiring about doing a gleaning (call #1), setting a date and time to glean (call #2), and checking in the day before for details (call #3) — for a total of one hour or less.

Volunteers And Donation Recipients

When SoSA organizes a gleaning event, it is juggling several logistical elements. Often, farmers invite gleaners when they are ready to plow a field in order to plant it with some other crop. That usually means timing is tight. Weather may also affect scheduling. If it rains, if the field is muddy from the previous day’s rain, or if the heat is unsafe, events may be moved or canceled at the last minute.

Potential volunteers know they’ll get little notice and that gleaning opportunities are mostly irregular. SoSA emails volunteers in the area of the farm as soon as possible in advance of a gleaning, but numbers of volunteers are often unpredictable. An event is capped with a maximum number of volunteers depending on the size of the field. Of course, more volunteers make for quicker work.

Hand washing stations are provided for volunteers if the farm does not have facilities nearby.

The SoSA staff leader informs all volunteers about established safety practices upon their arrival on the farm. Hand washing stations are provided for volunteers if the farm does not have facilities nearby. Depending on the crop, this introductory time may include a demonstration of the most effective harvest technique and tool safety. Incidentally, SoSA received a 2024-2025 grant from the U.S. EPA to develop grower-led training videos explaining how to safely harvest and handle surplus produce. The videos will be freely available in 2025. An earlier video showing some of the process of making measurements is available at the SoSA website, which references the project as Row-by-Row. Overall, the level of effort to train volunteers on specific field procedures to follow at each field is minimal: 20 minutes to teach volunteers at the farm, one hour to lay out the field and complete sampling, sorting and taking weights, and 30 minutes to process and deliver surplus produce to a food pantry.

Before the gleaning event, SoSA staff make arrangements with local food pantries, soup kitchens, shelters, senior centers, and childcare centers that provide food for those in need. Depending on the crop and the estimated quantity of food, staff call partner organizations that have both refrigerated or dry storage, or agencies that will cook the food in the next few days if it does not require cold storage.

SoSA maintains relationships with farmers who mostly donate with the motivation of doing good or giving back. When they invite gleaners to their farms, they point out the field, area, or rows they want gleaned to the SoSA staff person or field supervisor (a volunteer with particular training in leading field gleanings). SoSA gleaners are respectful of the farmer’s property and labor and aim to leave an area in the same good condition as they found it.

Taking The Measurements

When conducting field measurements, choose and mark off spots at random for the rows or areas being measured. Photo by Dr. Lisa Johnson, courtesy of the Society of St. Andrew

SoSA brings bags, boxes, or bins to collect the produce. If reusing bins, they must be washed with a bleach solution. Consider the weight and fragility of the crop when acquiring bags for gleaning. Smaller bags are better for berries. Larger bags are good for kale because it’s light, but filling a large bag with butternut squash would be too heavy for volunteers to handle.

Likewise, the measurement plots are small; hence, not a lot of time is needed to lay the plots out. Using spreadsheets as suggested in Dr. Lisa Johnson’s methods makes calculation easy and fun (Johnson, et al., 2018). One-time costs for food crates and the measurement wheel are less than $100.

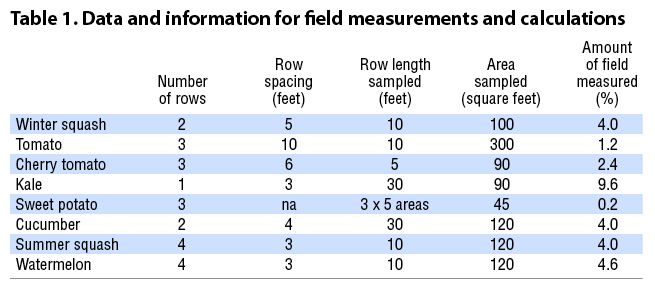

When SoSA provides measurements for farmers or for research purposes, it uses the method created by Dr. Johnson (Johnson, 2023). Volunteers measure the size of the area, length of rows, and distance between rows. This information is used to calculate the average of total row length per acre.

The next step is to choose and mark off three spots at random for the measurements. If volunteers are gleaning around the measuring person, it is helpful to mark off the areas and explain the process at the beginning of the event, asking non-measuring volunteers to avoid those selected areas. Table 1 shows the layout data that was adequate for the different crops and farm situation. In some locations the crops available for measurement and gleaning were in a single row so the measurements were taken at randomly selected sections of the row. In the case of sweet potatoes, a plot area was sampled. Regardless, the data from each field was statistically relevant.

Harvest each row portion thoroughly. Collect every piece of food, no matter its condition. Separate the produce into three categories: 1) Marketable, which meets grocery standards for sale; 2) Edible, which is still good/healthy, but does not meet those standards; and 3) Inedible, food that is spoiled, shriveled, or otherwise unsafe for human consumption.

Harvest each row portion thoroughly. Collect every piece of food, no matter its condition. Separate the produce into three categories: 1) Marketable, which meets grocery standards for sale; 2) Edible, which is still good/healthy, but does not meet those standards; and 3) Inedible, food that is spoiled, shriveled, or otherwise unsafe for human consumption.

Weigh each category for all three sample areas — a total of nine weights, three from each sample area. Find the mean weights of the marketable, edible, and inedible food between the three samples. Use the field’s total row length (number of rows multiplied by length of rows), the lengths sampled, and the average weights of the samples to calculate the whole field’s weights of marketable, edible, and inedible produce. These values are used in a spreadsheet to calculate marketable, edible, and inedible loss per foot and extrapolated to determine the total loss for that field. The loss for the fields is the most important information to share with the grower.

To extrapolate to loss per acre, use the row length and spacing to determine row length per acre. Multiply the marketable, edible, and inedible loss per foot numbers above by row length per acre to find the marketable, edible, and inedible loss per acre. This number may be compared with USDA Agriculture Census Data to provide an estimate of loss by county or state.

After the Event

Send the grower a thank you note after the event and include a table showing how much was gleaned and where it went. Include some pictures if you want. After extrapolating the measurement data to the entire field, explain what you found, which may be helpful in how they make business decisions in the future. Keep these records for your organization as well. It will help you decide how many volunteers to recruit and how many hours are needed at future events.

Thank your volunteers, and follow up with the agency receiving the produce. They may share photos of what they’ve prepared with the fruits or vegetables you donated.

The ultimate goal of this work it to help grower partners make decisions for their farms but also to gather as much information as possible about the reality of unharvested farm produce including type, quantity, quality, and reasons for the harvest shortfall. Understanding the magnitude of the post-harvest yield can lead to more opportunities to significantly increase gleaning, donation, and sales for the grower.

It also builds a more robust data set that may be used to develop predicative models for anticipating farm surplus, particularly on medium and small farms, well in advance of its actual occurrence, a key to working solutions. This procedure allowed SoSA to estimate a total of 30,151,000 pounds of surplus in Tennessee during the 2021 and 2022 growing seasons. That volume is large enough to incentivize problem solvers to take on this local loss challenge and find ways to put more produce into the donation, business, jobs, and/or income sectors.

Jeannie Hunter is the Regional Director of the Society of St. Andrew (SoSA) in Tennessee. Thomas O’Donnell is Sustainability Coordinator at USEPA – NEWS in Philadelphia, in the Sustainable Management of Food group. Kim Charick, Sustainable Materials Management Project Manager at the USEPA, Atlanta, Georgia, focuses on strengthening the recycling infrastructure to recover, prevent and reduce food waste. Any views expressed in this report do not necessarily represent those of the United States government, SoSA, or the Environmental Protection Agency. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.