Top: Active sort line with human picker at Atlas Organics’ composting facility in San Antonio, Texas. Photos by Aspen Hattabaugh

Aspen Hattabaugh

Atlas Organics operates a source separated organics (SSO) composting facility in San Antonio, Texas that processes residential and commercial organics. Atlas has a 10-year contract with the City of San Antonio to compost city-collected commingled food waste, food-soiled paper and yard trimmings. The composting facility, located at the city’s Nelson Gardens Landfill, processes organics in aerated static piles (ASP). To facilitate sorting, Atlas Organics introduced a first-of-its-kind AI (artificial intelligence) sort line in 2021 with the expectation that the AI-controlled robotic picking arms would replace one human picker apiece on the sort line — a notoriously difficult position to keep staffed in the compost industry.

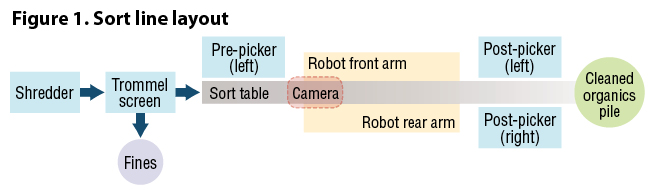

The technology set up started with a shredder that fed into a trommel screen to remove fines and improve contamination visibility. The shredded, screened organics traveled under a camera to identify contamination type and location. Based on a contamination priority list defining what should be picked out and the priority of removing that contaminant in comparison to others, the AI camera brain would tell the robot arms what to remove and where the arm should go to remove the contamination. The cleaned feedstock then fed into a grinder before being placed on an aerated static pile zone. The AI set up had been successfully used in Material Recovery Facilities (MRFs) and Atlas was the first to implement this in the field of organics.

Sorting Data Collection

Data collection began in January 2022 using two-minute segments of robotic picking video footage. The footage was used to quantify pick success — the successful removal of a contaminant from the feedstock stream — versus pick attempts — attempted and unsuccessful removal of a contaminant. Robotic pick success hovered around 55% for the first year of data collection but successful removal and attempts were very low overall, averaging only 4.2 successful picks for every 7.7 attempts per minute. Equipment downtime between October 2022 and May 2023 interrupted data collection for several months but began again in June 2023.

A site visit and an operational request to add fiber, encompassing paper, cardboard, and Tetra Pak® cartons, to the contamination list to remove some excess cardboard led to improving the pick attempts numbers from an average of 7.7 to an average of 60 attempts per minute. The increase in pick attempts was likely driven by the inclusion of fiber on the priority list (more contaminants to identify and remove from the feedstock), but what wasn’t known was if the improved attempt number resulted in more priority contamination removal and higher picking success rates.

Priority Contamination Removal Trial

This noted improvement in pick attempts led to several questions and a subsequent study to quantify the sort line’s ability to remove priority contamination and to determine the best sort line configuration for the site. The field study was designed to answer these questions:

- Did successful contamination removal increase with increased pick attempts?

- Which contaminants were targeted most? Was fiber targeted over higher priority contaminants?

- What set up provides the highest level of contamination removal?

- Are the robots removing contaminants worse than, the same as, or better than humans?

- What caused the most downtime for regular operations?

To answer these questions, the study utilized waste characterizations, tonnage throughput, and two-minute observation periods across four sort line picking scenarios, with each scenario running for a full 30 minutes of sorting time. The feedstock for the full study and all previously watched sort line footage was of the municipally collected green bin waste — the only material to flow through the sort line. Separate from the field study, downtime and cause were assessed. The four scenarios used were:

- Robots Only: Regular speed, two picking robot arms

- Humans Only: Regular speed, three human pickers

- Humans Only – Slow speed, three human pickers

- Full Sort Line – Regular speed, two picking robot arms, three human pickers

The Full Sort Line scenario represented the sort line set up for normal operations. Pickers sorted their respective waste into separated bins for waste characterizations. For regular speed scenarios, the sorting belt ran at 237 feet per minute, a function of AI necessity and shredder throughput. A slower speed scenario was run at 60 feet per minute for humans only to see if this markedly improved pick results. Picker numbers differed between the studies, so all data was averaged by number of pickers to make it comparable across scenarios. Picker locations and sort line flow are detailed in Figure 1. Throughput included the weight of total fines, contamination, and cleaned organics to calculate tons per scenario.

Study Results

Did successful contamination removal increase with increased pick attempts?

Post fiber addition, robot pick attempts increased significantly, from 15.5 to 102.1 per two-minute periods, an increase of 558.7%. Pick success, however, barely improved at all. After adding fiber to the contaminant list, pick success improved by only 1.6%, increasing from 55.3% pre-fiber to 56.9% post-fiber. Contamination removal did not increase with more attempts.

Which contaminants were targeted most? Was fiber targeted over higher priority contaminants?

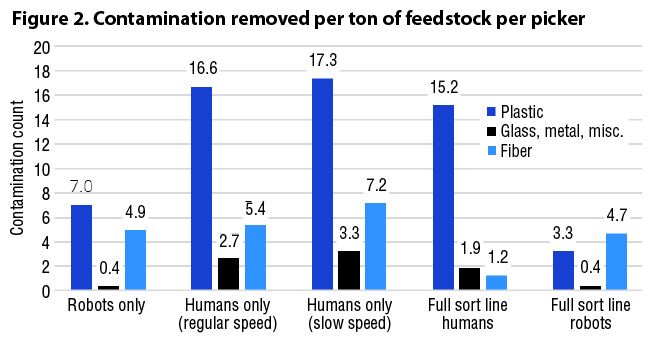

Figure 2 outlines the waste characterization data, presenting waste characterization counts of contaminants removed per ton of feedstock per sort line scenario. For the full sort line study, which combined the human pickers and two robotic arms, the human data and robot data are presented separately for comparison.

Humans proved to be over 80% better at removing plastic and 150% better at removing glass, metal, and miscellaneous items than the robots. Humans removed more priority contaminants in the Full Sort Line scenario alone than the robots did in the two robot participation scenarios combined.

Plastic, consistently the highest contaminant in the feedstock stream, was unsurprisingly the highest removed contaminant across most scenarios. The robots correctly targeted plastic for removal over fiber in the Robots Only scenario, although the robots removed very few contaminates overall during any study scenario. Surprisingly, the Full Sort Line data showed the robots removed more fiber than other categories combined. While this is hypothesized to be due to a pre-robot human picker pulling out unsuitable items before the robot could identify and attempt on them, the robots proved worse at removing the highest priority contaminants in the Full Sort Line scenario, the common staffing set up used on site (two robots and three humans).

What set up provides the highest level of contamination removal?

The Humans Only–Slow Speed scenario (sorting conveyor belt moving at 60 feet per minute) showed the highest contamination removal per ton of feedstock (Figure 2). Throughput lowered by nearly half for this scenario compared to the other three at regular speed (237 feet per minute). While this was the cleanest feedstock in terms of number of contaminants removed per ton, humans vastly outperformed the robots across all scenarios. The Full Sort Line Humans data was slightly lower than other Human scenarios, as the front pre-picker had to leave their station to address several robot issues that could be resolved without stopping the sort line. This negatively affected the human results, although they continued to outperform the robots, even with stepping out of their pick location.

Are robots removing contamination worse than, the same as, or better than humans?

As Figure 2 illustrates, robots were much worse at removing contamination than their human counterparts. Comparing the number of contaminants identified and removed by AI to the number of items identified and removed by the post-robot pickers gives some insight into how successful the AI and robots were at identifying the contamination in the feedstock stream.

For plastic, the AI identified 516 items in the feedstock stream, removed 215, ostensibly leaving 344 plastic items for the post-robot humans to pick out. The post-robot humans removed 679 pieces of plastic from the feedstock stream, 163 more pieces of plastic than the AI identified! The AI identified 0 pieces of glass and removed 0; post-robot pickers removed 8. The AI identified 43 pieces of metal and removed 7, leaving 36 for the post-robot pickers. They removed 56 pieces of metal from the stream. Across all priority contaminants, the post-robot pickers removed 27% more priority contaminants than were identified by AI.

During this portion of the Full Sort Line study, the robots attempted to remove less than 75% of identified contamination. Of these attempts, about half resulted in successful removal of the contaminant, staying right in line with the slightly over 50% removal success rate found during the two-minute pick success observations performed before and during the study. Looking at identified versus removed contaminants, only around 33% of identified contamination was removed by the robotics.

Prior to this field study, Atlas used targeted trainings for glass and metal by collecting specific categorical contaminants and running them through the sort line on an empty belt to film for use in training the AI. Despite these efforts, the AI still struggled with identifying and removing metal, particularly aluminum cans, and glass of any type from the feedstock stream.

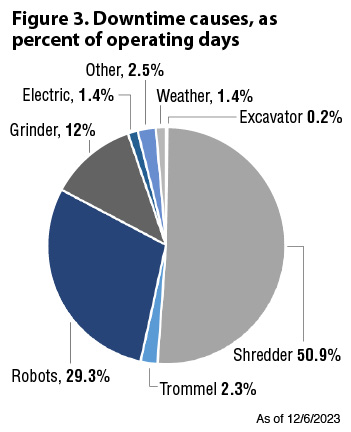

What caused the most downtime for regular operations?

Figure 3 outlines the downtime in percent of operating days from January 2022 through December 2023. As mentioned earlier in this article, the shredder, which was the first step in organics processing for the sort line and could not be bypassed, needed an engine replacement, causing a massive 50.9% downtime while an engine was shipped. Second only to the shredder’s delayed parts shipment, the robots caused the second highest amount of downtime at 29.3%.

Downtime aside, the robots required Atlas staff to have a high level of familiarity with their physical and technical operation. The robots required regular maintenance, frequent robotics and computer-based troubleshooting, familiarity with overall design and error codes, parts repair and replacement, and regular cleaning that required in-depth training and knowledge. As the second leading cause of downtime on the sort line, the robots proved to be inefficient for the location and feedstock for use as organics sorters.

Sort Line: Final Decisions

Many reasons contributed to the removal of the sort line robots, which were pulled from the sorting line in May 2024. The robots proved they were unsuited to the operating environment: outside, subject to weather extremes, and dust. The robotics components weren’t made for the specific feedstock stream and would often get tangled in the feedstock causing jams, downtime, and occasionally damage to the robots. The robots couldn’t be left alone to operate for the same reasons and required a high-level of human oversight and daily troubleshooting.

Non-wear parts started failing frequently due to increased picking attempts after fiber was added to the contamination list, including breaking robotic arms from the force of picks and pick arms getting stuck on and tearing holes in the sorting conveyor belt. With increased picking attempts, wear parts expected to be replaced on occasion started to fail frequently as well, with gripping mechanisms needing replacement within one day of operation. On top of these issues, the robots were proven to be ineffective and inefficient at identification and removal of contamination when compared to human abilities.

In this author’s opinion, the biggest factor for improvement lies in equipment design, which must account for the feedstock — dusty, gritty, amorphous, with seasonal variability in yard waste — and an operating environment that is outdoors, dusty, and subject to seasonal weather. This specific application of AI ultimately wasn’t successful at this location, but a wealth of knowledge was gained. AI may very well have a place in organics processing, but there is a lot of work to be done before deploying this technology to an operational site.

Aspen Hattabaugh has been an R&D Environmental Specialist with Atlas Organics since 2021. Previously, she worked in urban agriculture in Chattanooga, TN, helping relaunch a defunct community garden and leading compost and soil education programs. She holds a Master of Science in Crop & Soil Sciences from the University of Georgia and a Bachelor of Science in Biology from the University of Arkansas, Fort Smith. The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author.