“We finally realized what farmers were looking for — a way to reduce the amounts they were paying for ever more expensive chemical fertilizers,” says Gregor Keenan. Part II

David Riggle

BioCycle May 2012, Vol. 53, No. 5, p. 27

The composting facility is located on the Keenan family’s 70-acre farm, which utilizes the finished compost for soil amendment and nutrients. Their experience with the product led to an increased demand from other area farms.

One reason for investing in the in-vessel equipment was to comply with the United Kingdom’s Animal By-Products Regulations (ABPR), which govern composting of food waste. The Keenan’s had been composting green waste in open windrows. Under the ABPR rule, Category 3 materials, which include food waste from households and restaurants (called “catering waste” in the regulations), could not be composted in open windrows.

The shift from composting in windrows to vessels had a learning curve, but says Gregor Keenan, the company optimizes operations based primarily on temperature. “We’ve arrived at the view that the most important thing to analyze are temperature readings. If a certain mix works, we don’t really need to know in great detail why it works, we just need to know what the correct proportions are.”

Keenan’s Recycling receives a steady supply of fresh fish waste daily — shrimp, prawns, fish guts and water — from a processing plant about 10 miles away, which amounts to around 33 tons/week. The commingled green waste/food waste comes in larger quantities with seasonal variation. “We also get a small, but fairly regular amount of batter from another food processor,” adds Keenan. “It has a pH of about 4 and is quite oily and hydrophobic, so it’s not the easiest thing to compost and has to be introduced in small amounts to make sure you don’t overdo it. So there’s a wide variety of stuff and if we get something new, we always get it analyzed to see how it’s going to compost and make sure to introduce it slowly.”

Shortly after installing the in-vessel system, Keenan’s hired Graham Duguid as the operator. “Graham’s got a very good handle on the moisture levels and the proportions, putting in so many kilos of each material to get the mix just right,” continues Keenan. “He also looks at it in the mixer to see if it crumbles, how it falls. If it’s turning over in big slabs you know it’s not going to let any air through. It took us a while to figure out, but the optimum mix of a 4.5 ton blend for us is around 2.8 tons of commingled green and food waste shredded to a half-inch particle size, 880 lbs of fish waste, 660 lbs of batter and around 1,700 lbs of wood chips.”

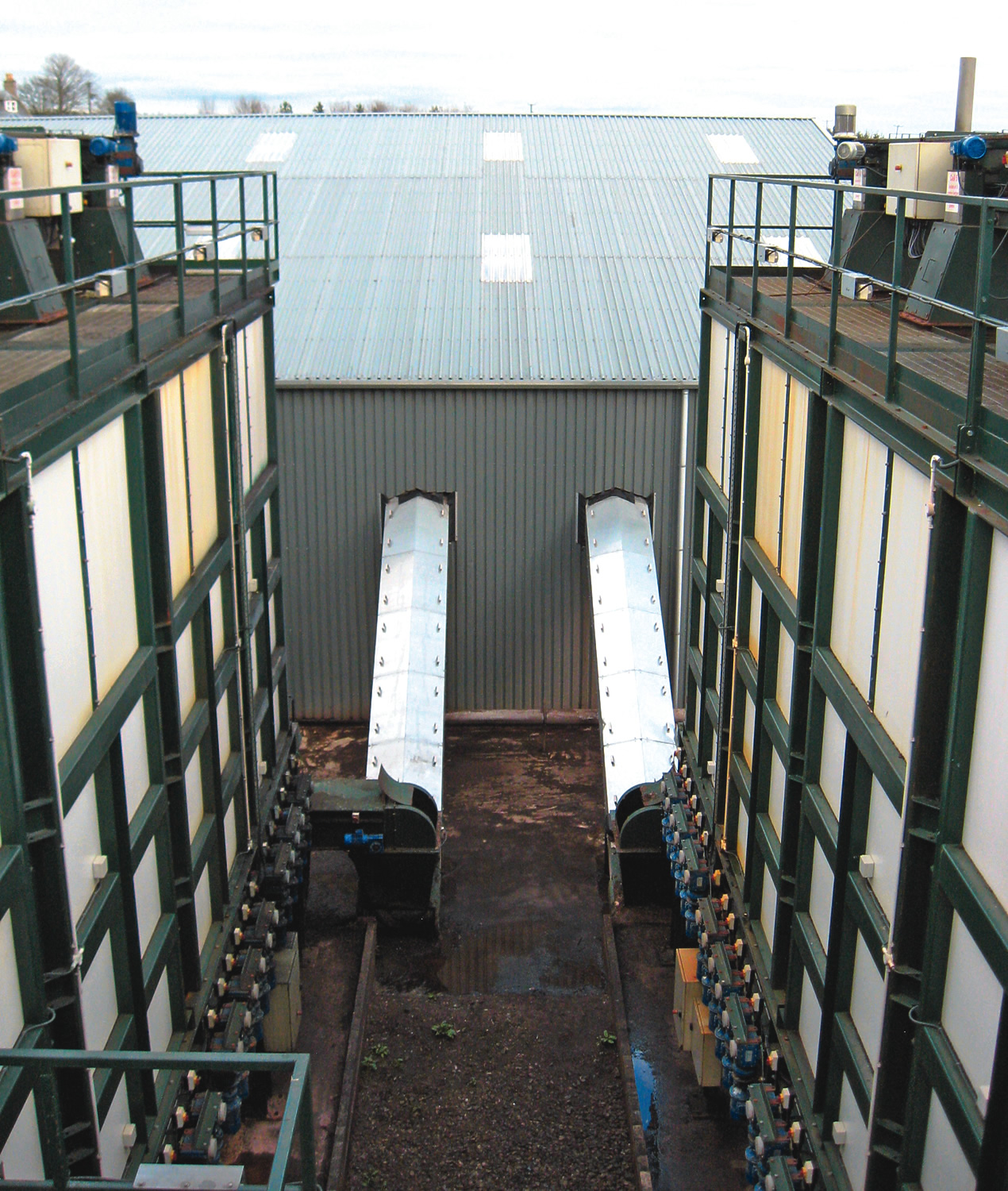

The VCU discharges material into the enclosed maturation building (left). Retention time in the units averages three days.

“For us, a big key is getting the best commercial value out of your system, which means just the right retention time in the columns,” says Keenan. “Traditional advice is usually to keep it in the vessel for 7 to 14 days. After we got the mix right, we found that wasn’t necessary. Three days in the VCU normally is sufficient. After three days, the half-inch material doesn’t resemble food waste at all and there’s no ammonia smell as you might expect.” The VCU discharges material into the enclosed maturation building, where it remains for another two to four weeks depending on material flow.

Compost Markets

Keenan’s Recycling is located on the family’s 70-acre farm. The composting operation takes up 9 acres, but much of the remaining 60 acres is planted with a rotation of wheat, cereals and oil rape seed. In 2005, most of the 5,500 to 7,700 tons/year of compost produced were applied to the Keenan’s property with some being made available to other local farmers for free.

The UK has a national standard for compost — the British Standards Institute Publicly Available Standard 100 (or BSI PAS 100) — that was originally launched in November 2002. Keenan Recycling Ltd. was certified as producing compost to this recognized standard in 2004. Countries within the UK differ as to some aspects of PAS 100. For example, in 2004 the Scottish Environmental Protection Agency decided that if compost made from source segregated materials (not mixed waste) is able to achieve BSI PAS 100 certification and there is a market, it is indeed a product and can be marketed and distributed as such. In practical terms, that meant the Keenans were able to market their compost to agriculture (always their largest potential market given their location) — if they could find anyone interested in buying it. They moved the price up to a nominal 50 pence per metric ton (roughly $1/ton), but that wasn’t the answer.

Using oversized wood chips in the initial mix is critical in a vertical system to allow air flow through the columns.

“When we focused on the equivalent fertilizer value of compost, that started to turn the tide,” Keenan reports. “Looking just at N-P-K and the prices farmers were paying for their usual supplies, we were able to work out that our compost had a direct inorganic fertilizer replacement value of around $14.50/metric ton for Green Compost (typically 8.7N/3.1P/6.0K kg/tonne) and up to $21/metric ton for the more nutrient rich Premium Compost with food waste (typically 18.4N/7.8P/8.3K kg/tonne).” WRAP (the Waste Reduction Action Programme) was doing similar calculations and by one reckoning worked out that a metric ton of compost typically contains about 15 lbs of nitrogen, 9 lbs of phosphates and 11 lbs of potash. Depending on the cost of the compost and transport, that means a farmer spreading the recommended 13.4 tons/acre (30 tonnes/ha) could save up to $118/acre (£180/ha) in fertilizer costs, noted a 2009 article in the Glasgow Herald.

One marketing challenge that had to be overcome related to restrictions on compost use resulting from the Foot-and-Mouth outbreak that led to the ABPR regulations. Many farms that could have used compost — most situated in that 20 to 30 mile transport radius that makes bulk transfer economical — were enrolled in the Quality Meat Scotland (QMS) assurance scheme for farms supplying trademarked “Scotch Beef” and “Scotch Lamb” to markets in the UK and around the world. For a period of time, QMS members were forbidden to use composts, even those achieving PAS 100 certification, due to remaining concerns within the scheme about the safety of compost in general.

Even though QMS eventually lifted the ban, “their questions did focus a lot of attention on the quality aspects of compost and a whole range of risk assessments relating to its use that will be useful in the long run,” explains Keenan. Today, local QMS members are actively encouraging compost use and Keenan Recycling’s products are in demand. In fact, the local QMS Monitor Farm — held to be an exemplar of the farming practices all QMS members should aspire to — now advocates the benefits of compost use, a striking indicator of how the situation has changed.

Keenan’s Green Compost from garden waste (produced in windrows) sells for around $4.50/metric ton and Premium Compost, made with food waste in the in-vessel system (with a higher nutritional value) is about $9/metric ton. A typical order, according to the company, is usually between 500 and 1,100 tons at a time, with 95 percent going to local agriculture. This past year compost has been selling as quickly as it’s made, with no stockpile of mature compost on site.

David Riggle is a former Managing Editor/International Editor of BioCycle and has been living and working in Scotland for the past 14 years. He has been employed by the Waste Services department at Stirling Council since 2001, and before that coordinated development of a Local Agenda 21 Plan with community and environmental organizations in Fife.