Top: The footprint of the Hermitage (PA) wastewater resource recovery facility includes food scrap receiving and preprocessing, followed by codigestion. Photo courtesy of City of Hermitage

Carol Adaire Jones

As highlighted in Part I of this series, water resource recovery facilities (WRRFs) have substantial untapped capacity for codigestion but have been slow to incorporate food scraps as feedstock due to several impediments:

- Food scraps are typically managed through the solid waste system and thus are less familiar than fats, oils and greases (FOG) and food and beverage processing residuals.

- Municipal solid waste (MSW) agencies traditionally have not collected them separately.

- Food scraps need further preprocessing — removing contaminants, reducing particle size, and adding liquid to create a slurry — to be suitable as an anaerobic digestion (AD) feedstock.

However, as demand for recycling food scraps is increasing, innovations in food scrap sourcing for codigestion are emerging. Part I discussed regional partnerships with the solid waste (or solid-waste-adjacent) sector, the predominant class of solutions employed by WRRFs. Part II features a relatively new business model with limited applications to date — WRRF vertical integration into food scrap recovery. Factors are highlighted that will affect the growth potential for the two different business models (external sourcing of food scrap slurry through regional solid waste/wastewater partnerships vs. investing in on-site preprocessing capacity). The last section of the article notes how the patterns of business models for sourcing preprocessed food scraps differ among private AD developers relative to the wastewater sector.

The distinctive feature of the vertical integration business model is wastewater utility investment in on-site Organics Receiving Facilities (ORFs) that have the capability for depackaging, as well as other preprocessing. Two wastewater utilities profiled below have adopted this business model.

Hermitage Municipal Authority

Located in western Pennsylvania on the Ohio border, the City of Hermitage Municipal Authority operates a Food Waste to Energy and Wastewater Reclamation Facility (WRF). In addition to its wastewater treatment program (with 3.5 million gallons average daily flow), the City of Hermitage has developed an organics recovery program that manages the acquisition, depackaging and preprocessing of food waste liquids and solids to serve as codigestion feedstocks. Wastewater Superintendent Tom Darby runs the program as a complementary business that provides revenues and cost savings to support the core mission of the authority — water quality.

The wastewater utility added food waste codigestion as part of Phase II of a $32 million upgrade of its facilities, which was completed in 2014. When its anchor client, a local dairy, began offering packaged products such as milk, yogurt and cottage cheese, in addition to unpackaged liquids, Hermitage installed an REM depackager, which perforates containers. Other food waste generators began offering a lot of solid packaged food waste. To manage this stream, the WRF purchased a Scott Turbo Separator, which removes packaging and creates a slurry. In 2020, it added a Veolia ECRUSORTM, which uses a screw press that results in less shattered plastic. Now 70% of the food waste is run through depackaging.

The first AD facility in its region to accept packaged food waste for recycling, Hermitage is well situated — on highways halfway between Pittsburgh and Cleveland — to serve as a regional hub for food scrap recycling for the numerous food manufacturing and food retail generators with zero waste goals located within its market area. Its anchor client continues to be the local dairy, its initial supplier. The WRRF is not required to have a solid waste permit for acceptance and processing of source separated food waste.

City of Muscatine WRRF

The City of Muscatine, Iowa, located on the Mississippi River border between Iowa and Illinois, operates a 5.5 mgd average daily flow Water and Resource Recovery Facility (WRRF). Motivated to reduce biogas flaring, Jon Koch, Director of the WRRF, decided to expand codigestion beyond FOG in order to make it economically feasible to invest in technology to produce RNG or electricity. Over the past eight years, the City has developed an organics recovery program that manages the acquisition, depackaging and preprocessing of food waste liquids and solids to supply as feedstock to the WRRF’s digesters. Koch established two key principles for the organics processing program: having a stable source of material from multiple sources; and being able to cover its costs with tipping fees, without being dependent upon the sale of biogas so that project would be viable even if energy prices tanked.

To support expanded codigestion, the city’s old recycling center at the transfer station two blocks away from the WRRF was converted into the Muscatine Organics Recycling Center (MORC), which has a Scott T42 Turbo Separator designed to process 10 to 20 tons/hour of packaged preconsumer waste. The High Strength Waste Department (HSWD) was created within the city’s Water & Resource Recovery division to manage the MORC, and is under the supervision of the Biosolids Department. The HSWD has its own budget and employs two full-time operators.

Feed hopper of Scott T42 depackager at the Muscatine MORC (left). Slurried food waste receiving station at the WRRF (right). Photos courtesy of City of Muscatine

Old tanks at the WRRF were repurposed for food waste receiving and mixing. An old digester is being retrofitted to increase AD capacity by 50%. Muscatine currently receives food waste from the numerous food manufacturers located nearby, including Nestle Purina, Kraft/Heinz, Conagra and West Liberty Foods, as well as stores from the HyVee grocery chain. Once the utility has increased digester capacity and the impacts of COVID-19 subside, allowing them to do more promotion and training, Koch hopes to expand its sourcing from grocery stores with zero waste initiatives, as well as from schools and restaurants.

WRRF Sourcing Strategies

Vertical Integration

These two examples of full vertical integration are flourishing — both in states without food scrap mandates/bans. Their organics processing facilities are the first in their regions to accept packaged food waste for recycling, filling a market gap for numerous food sector companies with zero waste goals located in their region.

Adding a new organics recovery line can create synergies with codigestion by providing a WRRF with additional control over food waste feedstocks and with greater information to guide management of digester feeds. Tom Darby noted the Hermitage Municipal Authority has ample space to store packaged food waste, and operators have become skilled at selecting among the stored organics to create desirable mixes for digester feeding.

However, WRRF adoption of full vertical integration of food scrap preprocessing is limited. Adding an organics recovery line for food scraps takes a WRRF further from the wastewater sector’s core mission — wastewater treatment. In addition, preprocessing food scraps may trigger more solid waste permitting requirements. In Iowa, the City of Muscatine was not subject to such permitting requirements for the MORC because it limits its intake to “single-source” food scraps directly from the generators, which are not mixed with municipal solid waste. Additional permitting requirements could curb the wastewater sector’s appetite for vertical integration.

Regional Partnerships

Regional wastewater and solid waste sector partnerships represent the most active WRRF strategy, with many variants. Currently many WRRF partnerships with solid waste sector organizations — public and private — occur in states with organics landfill bans or food waste recycling mandates. With mandates or bans, the solid waste sector is incentivized (and sometimes directly mandated) to provide source separated organics (SSO) collection and preprocessing.

Nonetheless some WRRFs are forging ahead with partnerships in states without mandatory requirements. For example, the Oneida-Herkimer Food2Energy program was initiated prior to the New York State food donation and food recycling mandate (effective January 2022) and both the solid waste and wastewater agency partners evaluated whether their investments would be economic if the recycling mandate under discussion did not materialize. And the Derry Township (PA) Municipal Authority (DTMA) had initiated high strength organic waste codigestion prior to when Divert marketed preprocessed food scrap slurry to DTMA from its nearby preprocessing facility. The Authority did not need to make additional infrastructure investments to accept Divert’s slurry.

A variety of partnership arrangements exist. A WRRF’s choice among public or private partners reflects, in part, local variations in the roles of public utilities and private contractors in regional solid waste collection and processing, as well as geographical and jurisdictional proximity. In the examples in Part I, large WWRFs with substantial AD capacity for codigestion are more likely to employ multiple partnership strategies, as diversifying sources of feedstock becomes increasingly important.

Some codigesting WRRFs have installed equipment to complement preprocessing done off-site, e.g., rock traps/grinders and screens. For example, East Bay Municipal Utility District (EBMUD) developed a patented pretreatment system when it pioneered codigestion of food scraps more than 15 years ago. However, the utility is now shifting to a model where its suppliers assume a greater share, or all, of the responsibility for pretreatment. Other WRRFs have adopted turnkey feedstock solutions, such as provided by Waste Management and Divert. It remains to be seen which approach will dominate as the market develops.

Ultimately, to achieve broad scale food scrap recycling, it will be essential to recycle organics currently in the MSW stream. Solid waste sector partners will supply the required SSO collection and preprocessing services if the public policies are in place and tip fees are set so that the service providers can cover their costs and generators have incentives to participate in SSO collections.

Private AD Developer Sourcing Strategies

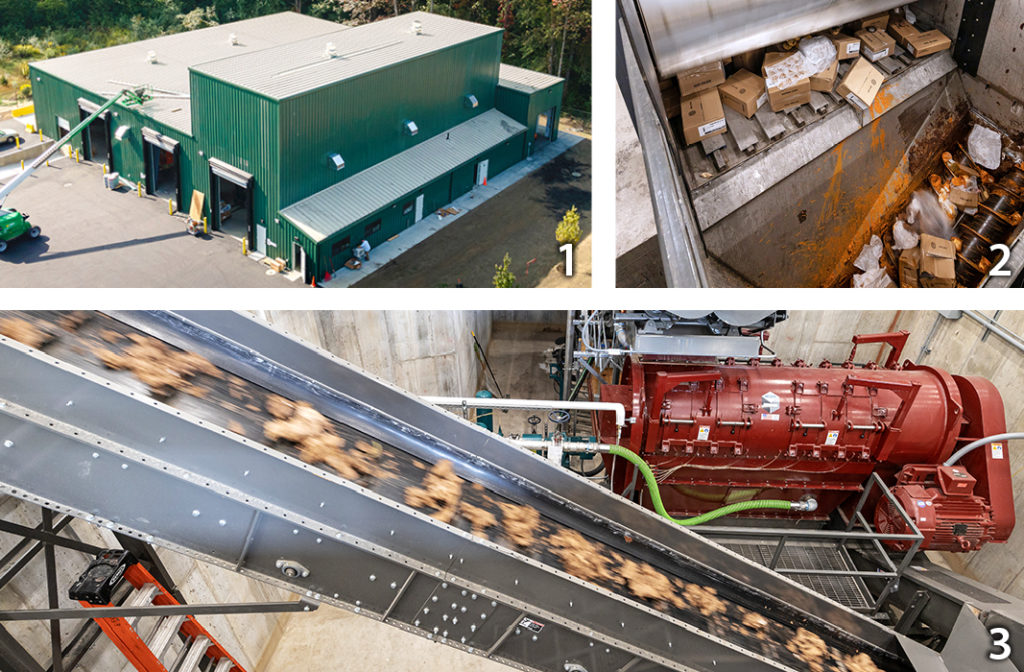

Vanguard Renewables’ organics recycling facility (1) in Agawam (MA) installed a KEITH Manufacturing Walking Floor (2) and a Scott Turbo Separator (3) to process food waste. Photos courtesy of Vanguard Renewables

In contrast to WRRFs’ predilection for solid waste partnerships, vertical integration appears to be the dominant strategy in the current flurry of activity by private AD developers. In the farm sector, Vanguard Renewables recently opened an organics recycling facility in Agawam, Massachusetts that is centrally located to supply food scraps for codigestion to the company’s six farm digesters in Massachusetts and Vermont. And with its new Farm Powered Strategic Alliance with partners Unilever and Starbucks and Dairy Farmers of America, Vanguard’s stated goal is to rapidly scale up the model in the U.S. Exeter Agri-Energy, a subsidiary of Stonyvale Farm in Exeter, Maine, preprocesses SSO for Stonyvale’s dairy manure digester. This is an example of a vertically integrated program with depackaging equipment at the farm to preprocess for codigestion the food waste collected by another subsidiary, Agri-Cycle Energy.

A number of developers of standalone food waste digesters also have vertically integrated into organics processing with depackaging. Examples include Commonwealth Resource Management Company (CMRC) in New Bedford (MA), which operates a food waste anaerobic digester at the Crapo Hill landfill; Quantum Biopower in Southington, Connecticut; and Trenton Renewables’ Trenton Biogas facility.

The Quantum Biopower AD facility (1) in Southington, CT (pictured in upper left) is colocated with a composting facility. Food waste is staged for depackaging (2). The slurry (3) is pumped to the digester. Photos courtesy of Quantum Biopower

Two factors contribute to the apparent gravitation of private developers to vertical integration and of WRRFs to regional partnerships with the solid waste sector. First, private developers gain the advantage of greater control over feedstock quality, quantity, and cost, and do not face the constraints on mission creep that impedes the adoption of vertical integration by wastewater utilities. Second, some WRRFs have an advantage in creating solid waste/wastewater sector utility partnerships because the two utilities report to the same official or otherwise have an ongoing public sector partnership.

Carol Adaire Jones, an environmental economist, is a Visiting Scholar at the Environmental Law Institute (ELI) and coleads its Food Waste Initiative. She was the Principal Investigator on the WRF study.