A Meal Gap Analysis identifies food shortfall in pounds and assists with planning for healthier surplus food donations.

T. O’Donnell and S. H. Katz

BioCycle October 2016

Food security depends on consistent access to affordable, nutritious foods that meet all requirements for an active, healthy lifestyle (Feeding America, n.d.). Tools are now available to understand the meal needs for community hunger relief at a level of detail that has not been widely accessible in the past. Feeding America, the largest hunger relief organization in the United States, developed Map the Meal Gap, a systematic methodology for calculating the annualized food budget shortfall of food insecure people in each county and congressional district in the United States. The method can be used for any area as long as representative economic and demographic data are available.

The key measures in a community that yields acceptable estimates of the Feeding America Meal Gap are: Poverty, employment, underemployment, percentage of the population that is African American and Hispanic, and household ownership. Using this tool, any community at any scale can analyze food insecurity as a way of building its strategies for making enough food available so everyone has access to affordable healthy meals. The focus in this article is on people who are not using the government safety nets within the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or other asset-based state programs. The severity of food insecurity is also important to understand so one very large group of individuals who are more likely to suffer from long term hunger and undernourishment in the United States are targeted.

The dollar estimates that Feeding America uses in its Meal Gap reports (Feeding America) can be easily extrapolated into an estimate of meals, and from there into pounds, hence, linking the Meal Gap to this more familiar measure to consider in wasted food management. Both measures, dollars and pounds, rely on underlying assumptions and averages (Gundersen et al., 2016); however, the value of this level of detail to planning and community engagement is significant and helpful. Qualitative goals are sufficient to drive actions while local communities learn to understand the needs and resources of their particular situations more quantitatively and individually.

Converting meals into pounds of food is aided by estimates of the average weight of a meal — 1.2 pounds per average meal (U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) (c), n.d.). Food weight, though, is a bulk measurement that is not related to nutrition. Calorie content is another important measure of nourishment but is not routinely used in Meal Gap analyses even though many studies have linked calories to obesity and other indicators of malnutrition (Condon et al., 2015, Feeding America(a)). In spite of its limitations, using weight as a measure does provide communities with a familiar and easy parameter or estimating how much food needs to be put back into the local food chain to project that sufficient food is available. Sourcing this food and then getting it into the hands of food insecure people is another chapter of the story that is well explored through the efforts of hunger relief organizations around the U.S.

Meal Gap Severity

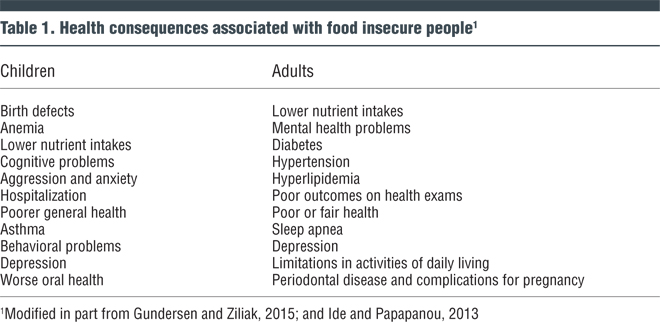

Feeding America methodologies identify those people who by nature of their response to the Community Population Survey live under conditions of very low food security. By recent estimates, 5.6 percent of U.S. residents were in this category in 2013 during part of the year, not including people and children who were homeless (Coleman-Jensen, et al., 2015). This helps to further refine an acute population that hunger relief agencies are trying to reach. New insights are available that demonstrate that people who are most food insecure suffer more from poor nutrition and do need new, more effective solutions. For example, Gundersen and Ziliak (2015) have shown that food insecurity leads to diminished health (Table 1) in a wide spectrum of viewpoints. Tarasuk and others (2015) have shown that health care costs increase dramatically among food insecure people. Surplus foods, properly managed and distributed, can improve the nutrition profile of the meals that severely food insecure people choose to eat, and thereby, the likelihood of reduced health care costs. This is a subject of upcoming articles in this series.

Local Meal Gap In West Philadelphia

The authors’ Urban Model for Surplus Food Recovery in West Philadelphia previously reported on Census Tracts in this section of the city, which are noteworthy for housing prestigious universities and hospitals (O’Donnell et al., 2015(a)). However, the rest of the neighborhood and adjacent Promise Zone Census Tracts have concentrated low income households with high levels of food insecurity. Analysis has been completed for the University City section of West Philadelphia that does not include large institutions. This report uses the Meal Gap, i.e., food insecurity values that Feeding America calculated for this project.

The “Calculating A Meal Gap” sidebar on page 32 describes the calculation methods and sources of data used to estimate the number of meals needed to match the Meal Gap, emphasizing surplus food donations. Each calculation applies best available metrics to determine a relationship between food insecurity and local food requirements expressed as pounds of food. In this case, pounds are useful because these are the same measurable units reported by donors and hunger relief organizations that receive and distribute food. The cost of food is based on purchasing food identified in the USDA Thrifty Food Plan (USDA (d), n.d.).

Pricing adjustments to the local cost are made by comparing the cost of a standard basket of food in different communities. The differential is reported as cost of a single meal. Another important metric is the percent of people who are eligible for government SNAP and WIC (Women and Infant Children) safety net programs.

Food insecure people who exceed the income or asset-based requirements for government support are left to rely on charitable donation sources for additional support. In addition, many people eligible for WIC or SNAP benefits do not use them. The reality is that some people will seek help with their food needs from the government or local hunger relief organizations and others will not. The Food System-Sensitive Methodology (FSSM) for transforming surplus food by developing productive new ways to keep it in the food chain (see sidebar), currently groups food insecure people who are not taking government support as part of the charitable component of the Meal Gap. Planning for surplus food availability is therefore determined for a portion of people who are eligible and all who are ineligible for SNAP benefits.

The Meal Gap sidebar shows a calculation data set for food insecure residents living in the University City census tracts that are west of the major institutions in the neighborhood. Confining the analysis to this section removed the reporting bias of low income university students who are attending high cost private colleges and universities. The project area’s income profile is similar to Philadelphia as a whole — 24.1 percent versus 21.7 percent low income residents — so Philadelphia values were used to fill any gaps in data for the project area.

The Feeding America Meal Gap for the project area is $1,296,449, which is equivalent to about 538,318 pounds of food. Of the 4,118 food insecure people, we calculate that 2,414 may seek only donations to meet their food needs. This estimate is dynamic, with different people passing through stages of food insecurity while the situation of other people is improving. The ranks of food insecure people, their numbers, severity of their situation, overall health and capability of meeting their own nutrition needs fluctuates along with other broad indicators of economic conditions. People who become sick or injured may find themselves food insecure for a time. As unemployment rates drop, more people are able to get jobs and move out of the realm of food insecurity. Severely food insecure people however, are least likely to be able to fend for themselves due to their many hardships. This analysis indicates that on average 44,860 pounds of food is needed each month to match the Meal Gap for people who would rely on charitable donations for supplemental food.

Estimating Surplus Food Availability

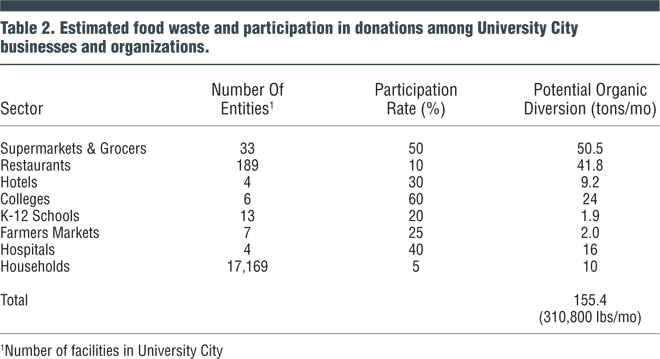

Potential surplus food availability was estimated using standard U.S. EPA and USDA data methods reported by other organizations (Buzby et al., 2014, Gunders, 2012, Drapper/Lennon, 2002). However, we supplement the standard source data with actual local data provided by experts on our project team, primarily food waste business leaders who are familiar with the organics management programs used in University City. Their local expertise allowed published average estimates of food waste to be calibrated to this specific community. A unique advantage of organics management specialists is their ability to provide evidence-based insight on participation rates as well as amounts of generated food waste from their experience in a community.

Table 2 shows the number of different food sectors in University City, along with a best estimate of food waste generation and current participation in diversion programs. The amount of wasted food from the different sectors that is suitable to feed people versus portions better used to feed animals, supply anaerobic digesters, or for compost is not known; however, experience suggests that the amount varies by location. Based upon reported donations (Feeding America (b), n,d.), a conservative estimate of 20 percent of total monthly poundage of wasted food can be captured and appropriately distributed, which would match the Meal Gap (FSSM). Regardless, it is evident in this example from University City that there is sufficient surplus food to shrink the local meal gap significantly.

Closing The Meal Gap, Providing Healthy Foods

Strategic hunger relief planning using the Urban Model guided by FSSM becomes a local community activity that connects key stakeholders across the food and health spectrum and creates new job opportunities. Continuing work of this type in many communities should lead to enthusiastic responses from local media, economic development groups and educators, which in turn may achieve other important components for success — outreach, education and social marketing to an engaged local community.

The ability to understand the local potential and approach to providing enough food to match a community Meal Gap with a focus on healthier, locally produced value-added products both encouraged and supported by local product purchases, is a recipe for success (FSSM). Otherwise one element of a real solution, a healthier population of individuals, is lost. Calorie counting for example, is too one-dimensional and should be integrated with measures of nutritional need fulfillment. A solution also should to be paired with public health measures — including child growth assessment, adult health indicators such as blood pressure and body fat and mental health indicators — to assess the health status of food insecure people. These linkages now provide ways for the organics waste management industry to align its goals to the larger public health industry. New opportunities for innovation exist at the nexus of these two national sectors of the economy.

The challenges of getting surplus food to those who can use it for various purposes is ever present and in need of a solution. Creating food delivery social enterprises that are financially sustainable through fee-for-services is an option for consistent, safe, and reliable delivery of surplus food to recipients. In this manner, the complex system of volunteer food pick-up and delivery is replaced with skilled trained people with a customer-facing perspective. Larger but still dispersed sources of surplus foods of the type created at institutions or by caterers may also create early success for this novel practice.

Upcoming articles in this series will address some of these circumstances and provide possible actions towards solutions. Now that sustainable food security and wasted food are becoming more prominent in communities, businesses and government at all levels, FSSM will continue to focus on issues of prevention, sustainable business solutions and associated health and wellness, all in the light of new national goals to reduce wasted food by 50 percent by 2030 or approximately two billion pounds each year in the U.S. alone. The good news for now is that enough surplus food appears to be available in many communities to meet the needs of people who rely on donations to help their situations. Our society spends a great deal of money on “Health Care”, treating preventable chronic illnesses that are directly linked to poor diets. The FSSM approach that makes better use of healthy foods that would otherwise be wasted, strongly suggests that investing more resources in “Food Care” will substantially increase health and well-being while reducing overall costs.

Thomas H. O’Donnell, Land and Chemicals Division, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, N.A.H.E. Region 3, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and Cabrini University, Radnor, Pennsylvania (odonnell.tom@epa.gov); S.H. Katz, Krogman Center for Research in Child Growth and Development, University of Pennsylvania and CEO World Food Forum, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (skatz2001@aol.com).

Note

This article was written in T. O’Donnell’s personal capacity, and not on behalf of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Any views expressed in this report do not necessarily represent those of either the United States government or the EPA. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.