Top: One of the requirements to be able to land apply biosolids is to meet standards for vector attraction reduction, which is measured by the volatile solids reduction. Photo by Ned Beecher

Sally Brown

Sally Brown

What do Chanel #5 and horse flies have in common? Not much you might guess. But one is the ying to the other’s yang. One’s purpose is to attract and the other is what may be attracted. People wear perfume or cologne to smell enticing. It is a tool to attract other people. Not necessarily on purpose, rotting food also can pack a powerful aroma. With that aroma, the flies come flying and the rats come running. Same thing, different target audience. This is the basis of attracting vectors.

People wear perfume or cologne to smell enticing to other humans. Rotting food has a similar attraction due to its smell, but entices flies and rats. Photo by Sally Brown

Vector attraction is one of those phrases where the reality hits home with much greater impact than the words on a page. A lot of people can recite the meaning, especially if you work with organics or wastewater. Vectors are bugs or animals that can build the bridge between potential disease-causing pathogens and the unwitting victim. Making your compost pile smell a little less appetizing is a way to reduce the potential for it to attract vectors. If you are working with biosolids you know that one of the requirements to be able to land apply the material is to meet standards for vector attraction reduction (VAR), which is measured by the volatile solids reduction. Volatile solids are carbon-based compounds that will emit gasses. More words that mean something very different on the page than they do in reality. Or at least they hit with much greater impact in real life than they do on the permit application. A way to think of this is deodorant.

Preventing Pathogen Spread

In wastewater the requirements for land application of biosolids include proof of pathogen reduction as well as volatile solids reduction. There is a reason for that — pathogens and vectors can be fast friends. The flies come for the smell and leave with the pathogens. Here the flies are the vectors. In addition to flies, likely culprits include rodents and birds. In each case, the vector provides the critical link or pathway between any pathogens in the biosolids and a person or other end receptor. A salmonella bacteria sitting in a pile of poop isn’t going to hurt anyone if it is left to itself. Only when the fly, rat or crow arrives does that salmonella have a way out. If/when that same fly, rat or crow comes into contact with a person or animal, the salmonella may have a new place to call home. One where it can do harm.

In wastewater, as in compost, killing the pathogens is often the same process as reducing the volatile solids. If you count on bugs (microbes) to eat the bugs (pathogens), easily digestible carbon will be eaten at the same time. Biological treatment, the basis for most wastewater processes and for composting, involves microbes transforming the easy to eat carbon compounds to longer chain and more stable compounds. The more complex and stable the carbon is, the less likely it will turn into gas and emit odors. Purely chemical processes like lime stabilization may kill pathogens but they will have limited impact on volatile solids reduction. This can translate to a smelly final product.

Pile of Class B biosolids on dryland wheat outside of Denver and boy did the flies come, recalls the author. Photo by Sally Brown

The typical processes in wastewater are centered around eating — adding air for the bacteria to eat the organics (secondary treatment) followed by anaerobic digestion. During secondary treatment, bubbling air through the influent degrades a good bit of the available carbon and destroys a portion of the pathogens. Anaerobic digestion is more eating but without oxygen, it goes at a slower rate. Assuring sufficient residence time in the digester is a way to both meet pathogen reduction requirements and reduce volatile solids.

In real life that means that primary sludge smells a lot worse than biosolids from the digester. Typically, anaerobic digestion will get you to PSRP (Process to Significantly Reduce Pathogens), which is typically a Class B product. You’ll need additional treatment to get you to PFRP (Process to Further Reduce Pathogens). Another term for biosolids that have reached PFRP (along with other requirements) is Class A. Depending on how you do this you have the potential to kill those two birds — pathogens and volatile carbon. Take the advanced thermal hydrolysis process used at DC Water in Washington, D.C. It increases heat and pressure prior to anaerobic digestion, causing microbial cells to burst and making their contents easy to eat. The resulting product, Bloom®, is low enough in vector attraction (read: it smells like soil and not poop) that it is a great product for your home garden. Here the heat kills the pathogens and the enhanced digestibility makes for sufficient volatile solids reduction to reach PFRP.

VAR In Composting

In the compost world, the issues of vector attraction and pathogen kill are a little different than in wastewater. Vector attraction is something that you worry about early on in the process, not at the end. Including food scraps in your compost pile creates the potential to start with some nasty smells. If your pile is initially anaerobic those smells will only intensify. With the smells come the vectors. The guaranteed place to spot eagles in the Seattle area is at one of the large composting facilities. The eagles happily come for the rodents who come for the rotten food. The composting facility is effectively an “all you can eat dinner” for the eagles with the buffet open 24/7. Those eagles are most likely to be found near the tipping area and will only frequent the curing piles as a place to nap and digest. No self-respecting rodent is going to use the curing pile as its home base.

As the microbes decompose the organics in the pile, the volatile solids and the pathogens are also reduced. Maintaining a pile at temperature (55°C) is the standard way to kill pathogens during composting. Those temperatures are reached early on as microbes are frantically feasting. Efforts at odor control at a composting facility are typically centered at the receiving area and for the initial stages of the process. This is the front end of the process in contrast to wastewater where odor mitigation centers on the final product. I’ve written about tools to reduce volatile solids — finished compost on top and even adding some biochar to the mix are both good options The key is to keep the pile aerobic and get it to temperature as quickly as possible. Both of these practices are or should be standard practice at commercial facilities. Both of these practices are much more of a challenge for home composters.

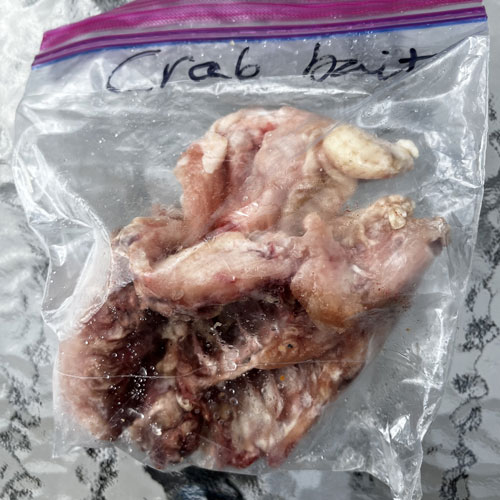

The guidance to leave meat and dairy out of a backyard compost bin is not based on their suitability as a feedstock (both compost just fine), but rather as a safety measure to reduce the potential for vector attraction. Photo by Nora Goldstein

In your backyard pile it is very difficult to get your pile to 55°C unless you compost in Phoenix in July. And even if they also bring eagles, no one wants to be the Pied Piper and have rodents making a b-line to their pile. That is why guidance often recommends leaving meat and dairy out of your backyard compost. Both compost just fine, making for a rich addition to your pile and a high nutrient compost. But both also have a high tendency to rot and smell like the Chanel #5 equivalent for those vectors. The guidance to leave them out is not based on their suitability as a feedstock, but rather as a safety measure to reduce the potential for vector attraction.

Hopefully this column has taken the terms vector attraction and volatile solids reduction out of the technical realm and given you a visceral understanding. Writing it, I was not intending to drive you to an immediate shower or to second guess your perfume preferences. But vector attraction is something that we see and smell every day.

A rose by any other name … And realize that your rotten chicken is a rose to a rodent.

Sally Brown, BioCycle Senior Adviser, is a Research Professor at the University of Washington in the College of the Environment.