Top: Photo by Tom Fisk

Nora Goldstein

Nora Goldstein

I think it is accurate to say that most news these days about climate change and what we can realistically do to significantly reduce carbon emissions is dismal and sometimes terrifying. That could be why I got so excited after reading a recent article in the New York Times (11/20/21), “The Midwestern City Where Rounder is Greener.” The article tells the story of Carmel, Indiana, a city of 102,000 north of Indianapolis, which has 140 roundabouts, with more on the way. Turns out roundabouts solve multiple woes, including changing human behavior.

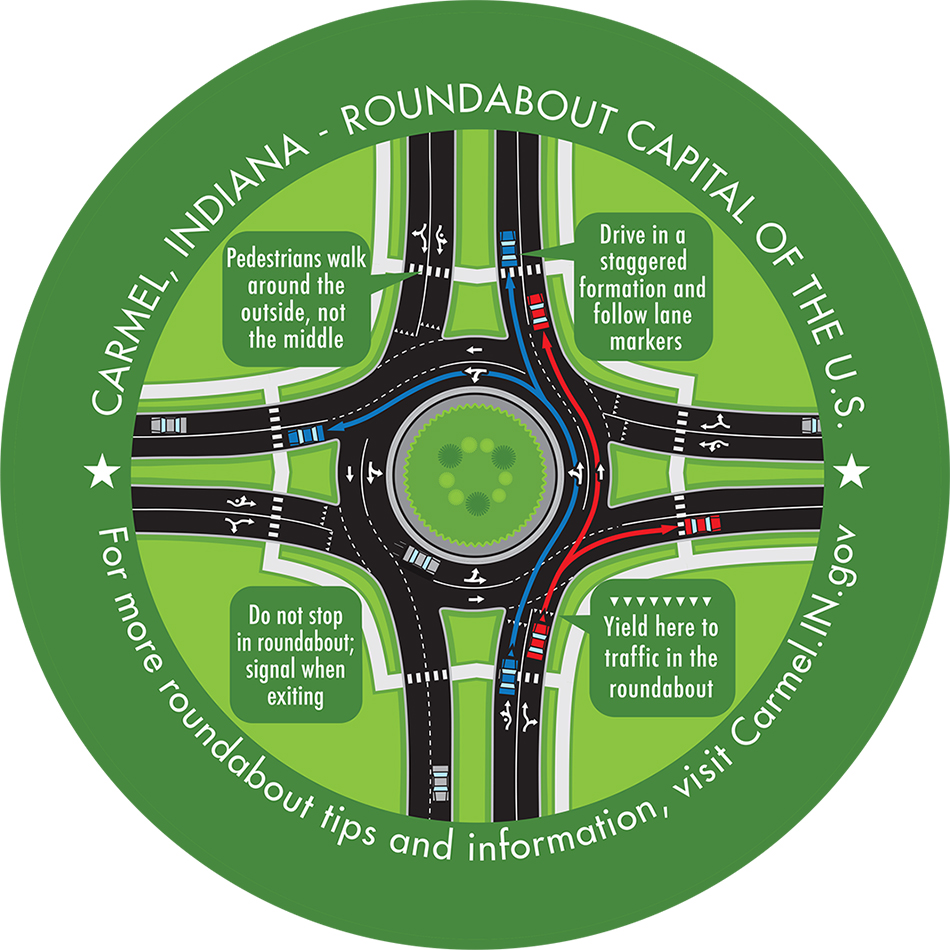

A roundabout is a type of circular intersection or junction in which road traffic is permitted to flow in one direction around a central island. They are intentionally designed to limit vehicle speeds to approximately 20 mph. Roundabouts typically are used on higher volume streets to allocate right-of-way between competing intersection movements, controlling vehicle speeds on four streets simultaneously. Entering vehicles yield to circulating traffic in the roundabout. Explains the Times article, “unlike traffic circles where cars enter at 90° angles, traffic flows into modern roundabouts at a smaller angle, drastically cutting the chances of getting T-boned.” Also, unlike rotaries or traffic circles, today’s roundabouts are compact (have a smaller diameter) and generally have fewer lanes. Upon entering the roundabout, drivers choose a lane based on their desired exit or destination. The graphic illustrates how traffic flows in a roundabout.

Climate Benefits

Because modern roundabouts don’t have red lights where cars sit and idle, less fuel is burned, leading to fewer emissions. Mike McBride, the former city engineer in Carmel, told the Times reporter that each roundabout saves about 20,000 gallons of fuel annually, resulting in 30 fewer tons of carbon emissions annually. Later in the article, it states that “carbon emissions per roundabout are highly dependent on location, construction, volume and time of day. A study of two roundabouts in Mississippi found a 56% decrease in carbon dioxide emissions; another calculated cumulative decreases at six roundabouts of between 16% and 59%. …. Overall, the Federal Highway Administration (FHA) has found roundabouts cause fewer emissions compared to signalized intersections, and said the differences can be ‘significant.’”

In addition to carbon emissions reductions, roundabouts offer climate resiliency benefits. When a storm knocks out the grid and thus power to traffic signals, roundabouts aren’t impacted, and thus traffic nightmares, like at traditional intersections, are avoided. And roundabouts typically are designed with green space — both in the center, and around the perimeter entry/exit points. This is an opportunity to amend the soil with compost post-construction, and create a bioswale in the center using engineered soil (with compost) to infiltrate storm water from the roundabout and support plant growth. In fact, greenery and sculpture in the center shifts the driver’s focus to the left, where it needs to be when entering the roundabout.

Traffic Safety

In addition to measurable climate benefits, roundabouts improve traffic safety. According to the FHA, more than half of all serious vehicle crashes happen at intersections. A recent study in Carmel by the Insurance Institute of Highway Safety (IIHS) “found that injury crashes were reduced by nearly half at 64 roundabouts in Carmel, and even more at the more elaborate, dogbone-shaped interchanges,” reports the Times article. That’s not to say this solution is accident-free, e.g., there are sideswipes and fender-benders. But drivers are traveling at much lower speeds, hopefully reducing vehicle damage.

The article also cites this statistic: “Vehicle fatalities in Carmel, according to a city study, are strikingly low; the city logged 1.9 traffic deaths per 100,000 people in 2020. In Columbus, Indiana, an hour or so south, it was 20.8.” Key to traffic safety, according a video on the Carmel website, is to go slow, always yield to vehicles in the roundabout, once in the roundabout drive in a staggered formation and follow the lane markings, and do not stop or pass another vehicle.

Behavior Change

It is hard to argue with all the advantages that modern roundabouts offer, especially when compared to signaled traffic intersections. Equally striking when I read the article is how well drivers in Carmel, as well as other cities, adapt to roundabouts once they are installed. Most people are initially skeptical but warm to them once they become accustomed to the new driving pattern, especially during rush hour. Noted Carmel Mayor Jim Brainard, “People love them here. You couldn’t take one out.”

A page on the IIHS website about roundabouts acknowledges that drivers may be skeptical of or even opposed to roundabouts when they are proposed. However, several IIHS studies show that opinions quickly change when drivers become familiar with them. “In three communities where single-lane roundabouts replaced stop sign-controlled intersections, 31% of drivers supported the roundabouts before construction, compared with 63% shortly after. In three other communities where a one- or two-lane roundabout replaced stop signs or traffic signals, 36% of drivers supported the roundabouts before construction compared with 50% shortly after. Follow-up surveys conducted in these six communities after roundabouts had been in place for more than one year found the level of public support increased to about 70% on average.”

These statistics resonate when thinking about how to implement solutions to reduce carbon emissions that involve changing human behavior. Some solutions give people a financial choice, e.g., you can pay less for trash service if you source separate your organics along with your recycling. Others are done “behind the scenes,” such as an electric utility shifting its energy supply to non-fossil renewables without a significant increase in rates.

Roundabouts fall into a different category as they are essentially “forced” on people as a solution. Carmel installed one in 1997 on the city’s outskirts and added another two the following year. Drivers had to change their behavior when encountering them but as it turns out, they quickly realized the benefits. Today, there are 140. This story has a happy ending.

What other significant carbon emissions challenges can we solve with a “roundabout” solution that also comes with measurable public benefits?