Top: Mass Natural Fertilizer Co.’s composting facility in Westminster (MA) was ordered to cease operations on July 20, 2022.

Nora Goldstein and Craig Coker

Mass Natural Fertilizer Co. in Westminster, Massachusetts, was one of the first fully permitted solid waste composting facilities in the Northeast, opening in 1987 as an adjunct operation for Westminster Farms, an 800,000-hen egg farm. Realizing it needed a full-time manager of the composting operation, Bill Page, Sr. was hired in 1989 to be the composting facility manager. He acquired Mass Natural Fertilizer Co. (Mass Natural) as a stock purchase in 1994; in 1995, Page purchased Westminster Farms and changed the name to Molly Hill Farms.

In 2002, because of the competition from larger egg farms, Page was going to lose the land through foreclosure (he had already closed the egg farm). He contacted Seaman Paper, which diverted its short paper fiber to Mass Natural for composting, to see if the company would come to the auction and bid on the land so that it would still have an outlet for its short paper fiber — and thus help keep Mass Natural in operation. Otter Farm, Inc., a subsidiary of Seaman Paper, was the high bidder at the auction.

In addition to a Site Assignment from the Westminster Board of Health and the solid waste composting permit from the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP), Mass Natural also had an agricultural composting permit. In 2018, MassDEP recommended that Mass Natural replace its existing permit with a Recycling, Composting or Conversion (RCC) permit. That permit was finalized in October 2020 (it also replaced the Site Assignment from the town).

In addition to a Site Assignment from the Westminster Board of Health and the solid waste composting permit from the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP), Mass Natural also had an agricultural composting permit. In 2018, MassDEP recommended that Mass Natural replace its existing permit with a Recycling, Composting or Conversion (RCC) permit. That permit was finalized in October 2020 (it also replaced the Site Assignment from the town).

Primary feedstocks composted by Mass Natural include short paper fibers, cranberry hulls, and industrial food processing wastes such as potato chip residuals and tea leaves, and yard trimmings. “We do not take residential and commercial food waste,” says Bill Page, Jr., who along with his wife Diane purchased Mass Natural from Bill’s father in 2016. “Our focus is clean food waste streams — the cleaner the better.” Mass Natural’s permit did not allow wastewater treatment biosolids to be accepted. Markets for its compost products and blends include landscaping, turf establishment, landfill cover and soil remediation.

Enter PFAS

In October 2020, MassDEP finalized a Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) for PFAS (Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) in drinking water of 20 nanograms per liter (ng/L) or 20 parts per trillion (ppt). MassDEP’s MCL applies to six PFAS chemicals: Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA), Perfluorooctane Sulfonic Acid (PFOS), perfluorohexane sulfonate (PFHxS), perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), perfluorohepatanoic acid (PFHpA), and perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDA). The MCL is an enforceable standard, set at a level that is safe to drink that water for an entire lifetime. There are currently no established federal regulatory limits for PFAS in drinking water. (EPA has issued drinking water health advisories for PFOA and PFOS, and is working towards establishing National Drinking Water Regulations in late 2022/early 2023.) MassDEP also established cleanup standards for the same six PFAS compounds in groundwater and soil that are 20 ppt and 0.3 to 2 micrograms per kilogram (µg/kg) or parts per billion (ppb), respectively.

In a fact sheet on the MCL for drinking water, MassDEP points out that “there are many gaps in the current scientific literature, but it is believed that PFAS may affect human health. Some of the research about health effects of PFAS is based on animal studies, and scientists are still unsure of the difference between how animals and humans respond to PFAS. …. It’s also important to keep in mind that health effects associated with PFAS are not specific to just PFAS — they can also be caused by many other factors. As a result, it is not possible to link a person’s drinking water exposure to PFAS with any former, current, or future health effects.”

In February 2022, private drinking water wells along Bean Porridge Hill Road in Westminster — the same road that Mass Natural is on — were found to contain certain PFAS chemicals regulated by the drinking water MCL. PFAS concentrations in the private wells were found to exceed Imminent Hazard Levels as described in the Massachusetts Contingency Plan (MCP), a set of regulations that includes the new PFAS drinking water, groundwater and soil standards. Subsequent additional sampling revealed PFAS impacts in additional private wells along Bean Porridge Hill Road, including the property where Mass Natural is located (65 Bean Porridge Road). “MassDEP has identified Mass Natural, as operator of the composting facility, and Otter Farm, as owner of the property, as Potentially Responsible Parties (PRPs) for the private well contamination under the MCP based upon MassDEP’s belief that the PFAS contamination is migrating in groundwater from the 65 Bean Porridge Hill Road property to the impacted private wells,” according to a website established by Mass Natural and Otter Farm and their Licensed Site Professionals (Lessard Environmental, Inc. and Tighe & Bond).

On March 31, 2022, MassDEP issued Notice of Responsibility (NOR) letters to Mass Natural and Otter Farm. “Upon receipt of the NOR letters, Mass Natural and Otter Farm have been working cooperatively to test additional private wells, provide bottled water, and install Point of Entry Treatment (POET) systems for private well owners with PFAS-contaminated wells as part of an Immediate Response Action Plan (IRA Plan) under the MCP,” notes the website. “Mass Natural and Otter Farm also continue to investigate the full extent of private well contamination allegedly emanating from the 65 Bean Porridge Hill Road property, as well as whether other potential sources of PFAS contamination that may be present in the study area.” Documents available on the website, including results of PFAS sampling of compost and materials (i.e., feedstocks) at Mass Natural and weekly drinking water well sampling, were utilized by BioCycle when writing this article.

“Mass Natural has been operating as a fully permitted composting facility for more than 30 years, and the first time it was required to test for PFAS was on March 15, 2022,” notes George Hailer, an attorney with Lawson & Weitzen who was retained by Mass Natural. “It also is important to point out that the stringent MCL for PFAS were established for drinking water, groundwater and soil, not materials like the ones composted at Mass Natural. Also, why did MassDEP implement a level so low when there will be exceedances everywhere? And PFAS chemicals are not like asbestos or lead, where there is a direct causal connection between pollution and illnesses.”

As an aside from the authors, one point of view is that PFAS chemicals are like heavy metals, in that they don’t decompose or chemically modify in a compost pile so that input equals output (this presumption needs to be scientifically validated). This is one reason why composters evaluating some new feedstocks will review feedstock heavy metal concentrations against their state’s applicable compost product heavy metals limits.

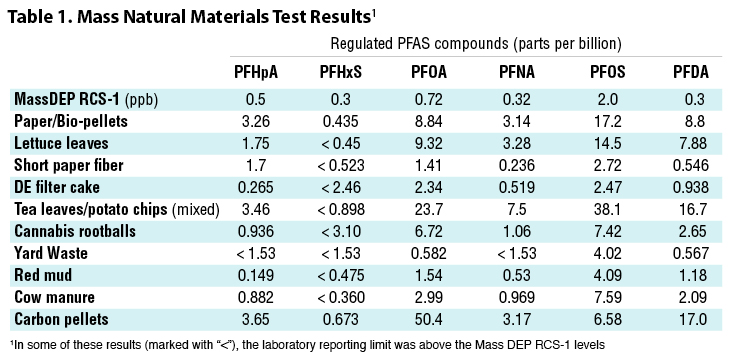

Materials tested at Mass Natural were landfill cover, golf course material, fiber biopellets, potting soil, finished compost, the composting windrows, loam, paper, lettuce waste, tea leaves waste, and cannabis roots. The findings were compared to the six PFAS compound limits established for soil, which the MCP defines as “any unconsolidated mineral and organic matter overlying bedrock that has been subjected to and influenced by geologic and other environmental factors, excluding sediment.” The Massachusetts regulations (310 CMR 40.0361) set forth two reporting categories for soils: RCS-1, which applies to locations with the highest potential for exposure, such as residences, playgrounds and schools, and to locations within the boundaries of a groundwater resource area. Reporting Category RCS-2 applies to all other locations. RCS-1 reporting thresholds were used in the findings.

Elevated levels were found in almost all the materials tested based on the PFAS MCLs for soils as shown in Table 1. The data in Table 1 are the highest readings among multiple samples of each material and are reported in parts per billion (equivalent to 1 inch in 15,782.8 miles). Clearly, these PFAS chemicals are ubiquitous.

Source: Table 4a, Summary of Raw Material Pile Composite Sample Analytical Data, Compost and Material PFAS Sampling Program

On May 17, 2022, MassDEP issued a Universal Administrative Order (UAO) to Mass Natural to “immediately cease and desist from selling or otherwise distributing any material that would exceed Reportable Concentrations of PFAS if used in an area designated as ‘Groundwater Category GW-1’ [of the MCP] and to, within 10 days, plan for sampling the products offered for sale or distribution at the Site described as ‘Screened Topshelf Loam,’ ‘screened compost,’ Farm Mix (unscreened compost), ‘Pick-up Truck of Soil,’ and ‘BYO 5 gallon bucket.’” In Massachusetts, there are three classifications of groundwater: GW-1, which is “Concentrations based on the use of groundwater as drinking water, either currently or in the foreseeable future”, GW-2 which is “Concentrations based on the potential for volatile material to migrate into indoor air”, and GW-3, which is “Concentrations based on the potential environmental effects resulting from contaminated groundwater discharging to surface water.”

The GW-1 groundwater limits were chosen by MassDEP as it “could be used as drinking water, including private wells,” said the UAO. At the end of June 2022, Mass Natural voluntarily submitted 30 additional sampling results to MassDEP (taken in late May and early June) showing that most of the materials sampled at the Site contain one or more PFAS compounds at levels exceeding MCP standards (see Table 1). The specific materials with exceedances included landfill cover; golf course material; fiber biopellets; potting soil; compost; “turkey pad” materials; Greif paper, “windrow;” and Top Shelf (loam). The data were inconclusive for Seaman paper, lettuce and tea leaves waste, and cannabis roots.

Mass Natural sampled and submitted all the materials again during a 5-day period (7/7/22-7/13/22). On July 20, 2022, the company received a second UAO that suspended its RCC permit immediately, requiring that composting operations at the site cease. “MassDEP has determined that operation or maintenance of the facility poses a threat to public health, safety, or the environment due to the presence of PFAS contamination in materials and groundwater on the Site and in over 100 private drinking water wells off-site,” stated the UAO. “…Within 30 days of the date of this Order, [Mass Natural] submit to MassDEP for its review and approval a plan to take appropriate remedial measures to protect public health, safety, and the environment, including but not limited to removal of all materials … exceeding PFAS standards from the Site.”

On August 9, 2022, Mass Natural and Otter Farm, Inc. filed an appeal of MassDEP’s permit suspension. The appeal, submitted by the two companies’ attorneys, points out that the UAO “is not consistent with applicable laws and regulations.” It explains that the UAO “does not apply the proper standards and metrics for assessing acceptable levels of PFAS in the materials at issue, ignores proper testing protocol in the MCP, and fails to identify crucial background levels for PFAS. …. Critically, however the UAO ignores the constituents and contents of the material that has been tested for PFAS.” Specifically, states the appeal, “the PFAS contained in the materials tested is measured against the RCS-1 values under the MCP, which apply to soil.”

What’s Next?

BioCycle interviewed Diane and Bill Page, Jr., along with their attorney George Hailer, on a video call in August 2022. The tragedy of the situation for all parties impacted was palpable. “The PFAS situation took us by total surprise, and now we are under the gun,” says Bill Page. “Up until a couple months ago, we were never asked to test for PFAS. The first round of tests we did was the first time we ever had to test. We’ve been doing everything that MassDEP and others have asked us to do. We’re not sure what direction this is going to head, but as soon as MassDEP comes up with a protocol for materials testing, we will follow it. It has been a learning curve.”

Hailer adds that Tighe & Bond, one of the licensed site professionals being used, has submitted testing protocols to MassDEP seeking the agency’s oversight and approval. “The methodology of some of the originally proposed testing couldn’t be done because the MCLs established for PFAS couldn’t be used with an EPA-like methodology,” he says. “It’s a situation of having so many samples being analyzed and labs being available that are capable of testing these kinds of chemical compounds — and in some cases the lab’s detection limit isn’t as low as MassDEP’s soil standards (for S-1 soils and GW-1 groundwater). The bottom line is that Mass Natural’s operations have been suspended and we don’t know where the facility needs to be with testing results in order to reopen.”

A critical next step for the organics recycling industry is to ensure, as more states and the federal government take steps to regulate PFAS chemicals, that the limits being established are based upon rigorous toxicology and risk assessments, along with analyses of background levels of PFAS, explains Hailer. “The science has to support limits that people can live with and at the same time, address the environmental impacts.”

Mass Natural has not started a piece of equipment since July 22. “All the vendors that we were servicing, where are they taking their materials,” asks Page. “Where are the tea leaves, chips and paper going? They can’t go to a landfill. Waste reduction has been a huge push by this Administration. When MassDEP does allow us to open up, it will be quite a bit more expensive to operate. And the situation didn’t just kill the reputation of Mass Natural. It has the potential to kill the reputation of composting across the board. PFAS is everywhere, and it is just starting to hit the radar. The situation is very, very frustrating. For 33 years, it has been fun coming to work. It is not fun anymore.”

Nora Goldstein is Editor of BioCycle.net and BioCycle CONNECT. Craig Coker is CEO of Coker Composting & Consulting near Roanoke VA and is a Senior Editor at BioCycle CONNECT. He can be reached at ccoker@cokercompost.com.