Top left: Community composting training engaging families and youth; Top right: Food scraps delivery handled by CompostableLA (Los Angeles); Center: Black Dirt Farm’s bagged compost (Stannard, VT). Photos courtesy Institute for Local Self-Reliance and Census respondents CompostableLA and Black Dirt Farm.

Clarissa Libertelli

Even as community composting increasingly makes its voice heard in the national composting conversation, data on the sector — key for both advocates of community composting and the composters themselves — can be hard to come by. The newly released report, A Growing Movement: 2022 Community Composter Census, from the Institute for Local Self-Reliance (ILSR) aims to fill that gap. Its goal is to document the distinct nature of the community composting sector and to serve as a baseline for measuring its future evolution. The findings reveal that while it is true community composters face a unique set of challenges in an economic and political landscape that favors industrial operations, the sector has the potential to boom.

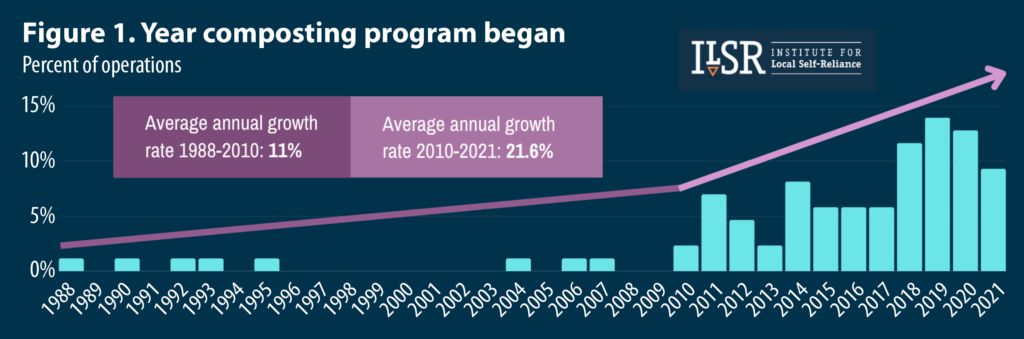

And perhaps the boom has already started. The Census data shows community composting operations are on the rise: 90% of composting operations started since 2010, with over half starting up since 2017 (Figure 1). These findings are in line with the increasing annual membership of ILSR’s Community Composter Coalition, which grew by 23% in 2020, 44% in 2021, and 48% in 2022.

The Census was sent out in 2022 via email to 359 community composters in ILSR’s database. A total of 86 responded (24% response rate). Because Census participants represent a wide variety of operational types, the ILSR report focuses more on describing the data collected rather than relying solely on statistics such as averages.

Operations And Scale

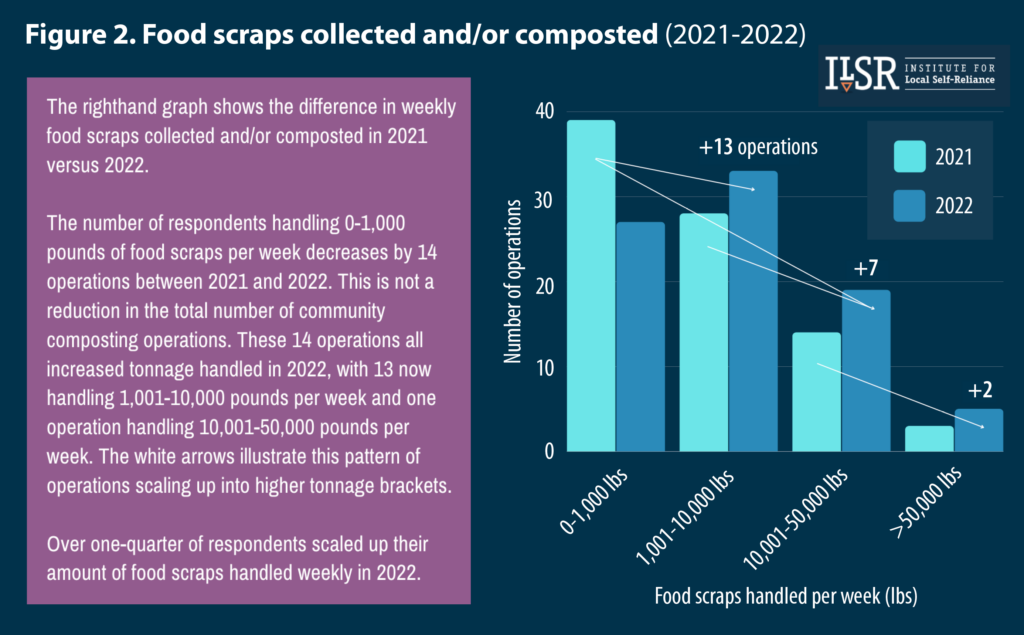

The results reveal that operations are scaling up, with over one-quarter increasing their weekly tonnage of food scraps handled from 2021 to 2022 (Figure 2). The method of scaling up varies according to specific needs, from a single site that ups its processing capacity to the development of a distributed network of sites. Because community composting is inherently locally-based, there is no universal model of what it looks like.

Solar powered three-bin system from Census respondent Peels and Wheels Composting. Photo courtesy Peels and Wheels Composting.

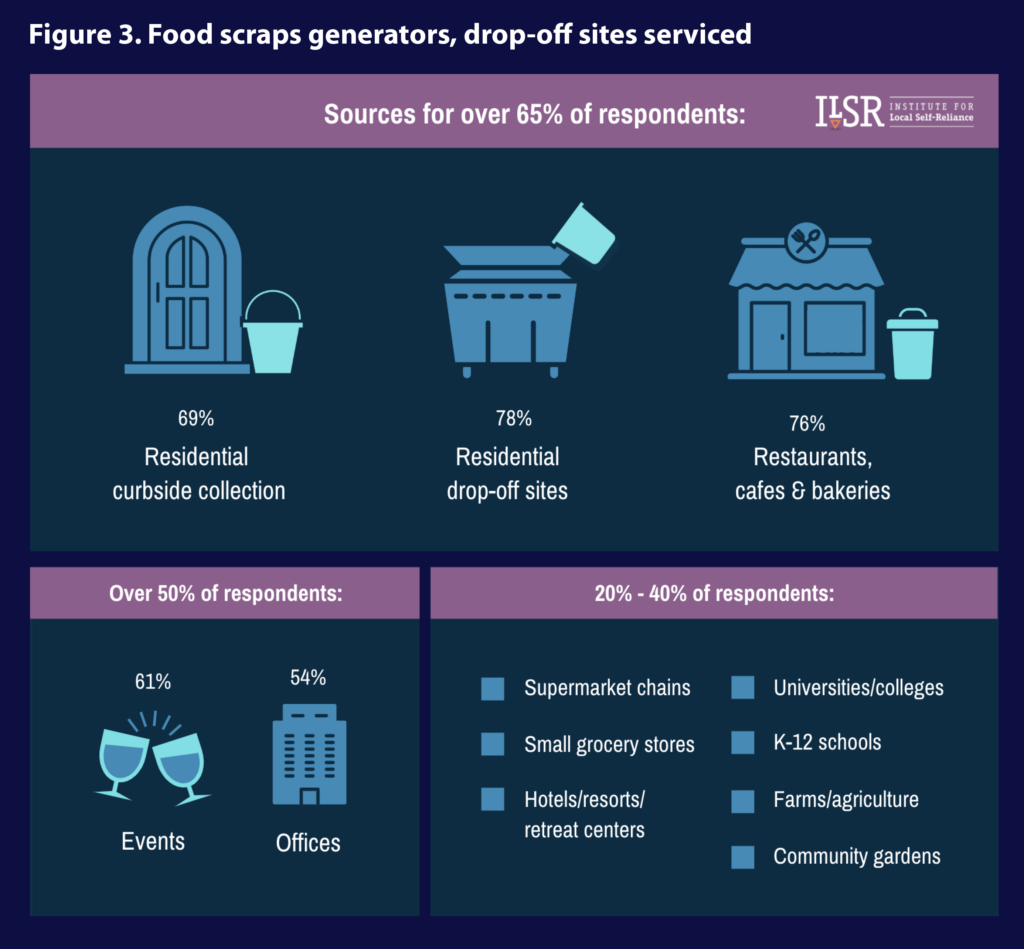

Similarly, the Census data reveals a wide variety of program types at vastly different scales. Respondents report a wide-ranging array of services provided, types of clientele (Figure 3), revenue sources, composting methods, compost end uses, and more (see Part I for more details). This diversity means that there are no one-size-fits-all solutions for many of the challenges facing community composters, such as how to scale up, find adequate equipment, and navigate local regulations. But diversity is also one of the strengths of community composting, in that operations are dynamic, flexible, and often sensitive to their local context. With 33 states, plus the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Canada represented, community composting is shown to be adaptable to a variety of situations and geographies.

Positive Impacts, Job Creation

Community composters are not only shaped by their communities. They also are uniquely positioned to impact them in return. In part, this is because the compost stays local. The vast majority of respondents with composting operations locate their sites within the areas they serve, and around half or more identify end uses for their compost as home gardens, community gardens, farms, and client giveback. As one respondent put it, “All the food we process comes [from] individuals, small businesses and CBOs [community-based organizations] within a mile of our farm. The compost produced returns back to gardeners within the community.” Models like these both cut down on transportation costs and keep the benefits of composting production and application close to home.

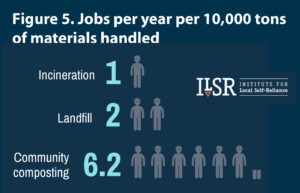

Local economic development is another positive impact. The non-industrial processing and distributed scale of community composting make an encouraging recipe for local job creation. Using the job factor from this Census’ data analysis based on full-time jobs only (Figures 4 and 5) and the U.S. EPA’s 2018 waste generation data, ILSR extrapolated that if half of the food scraps flowing to landfills and incinerators were diverted to community composters, over 50,000 new jobs could be created. (For context, the coal mining industry in the U.S. employs around 59,000 people as of 2023.) Furthermore, this number does not account for additional job creation from expanded collection services.

Local economic development is another positive impact. The non-industrial processing and distributed scale of community composting make an encouraging recipe for local job creation. Using the job factor from this Census’ data analysis based on full-time jobs only (Figures 4 and 5) and the U.S. EPA’s 2018 waste generation data, ILSR extrapolated that if half of the food scraps flowing to landfills and incinerators were diverted to community composters, over 50,000 new jobs could be created. (For context, the coal mining industry in the U.S. employs around 59,000 people as of 2023.) Furthermore, this number does not account for additional job creation from expanded collection services.

In addition, the Census indicates that community composting operations employ a significantly higher percentage of people of marginalized identities, such as women and members of the LGBTQ+ community, than does the commercial solid waste industry. For example, the traditional solid waste industry workforce is 83% male; conversely, community composters report an average of 33% male staff. Similarly, the communities these composters serve include rural areas, urban neighborhoods, and a relatively high percentage of people of color and people of Hispanic/Latino origin. This is significant as community composting has the potential to mitigate the environmental burdens that disproportionately face these same communities.

A majority of respondents (71%) also provide community engagement opportunities. Over half offer educational programming for schools, whether that means field trips to composting sites or traveling to classrooms to present to students. More than a third offer free training and volunteer opportunities; close to 30% offer paid training. On average, community composting operations have 7 volunteers involved. The impact of this kind of community engagement programming is difficult to quantify, but increased environmental education, community bonding, and encouraging local stewardship, are just a few of the potential impacts.

Census respondent Chickadee Compost (Sargentville, ME) utilizes the windrow composting method. Photo courtesy Chickadee Compost

Strengthening The Movement

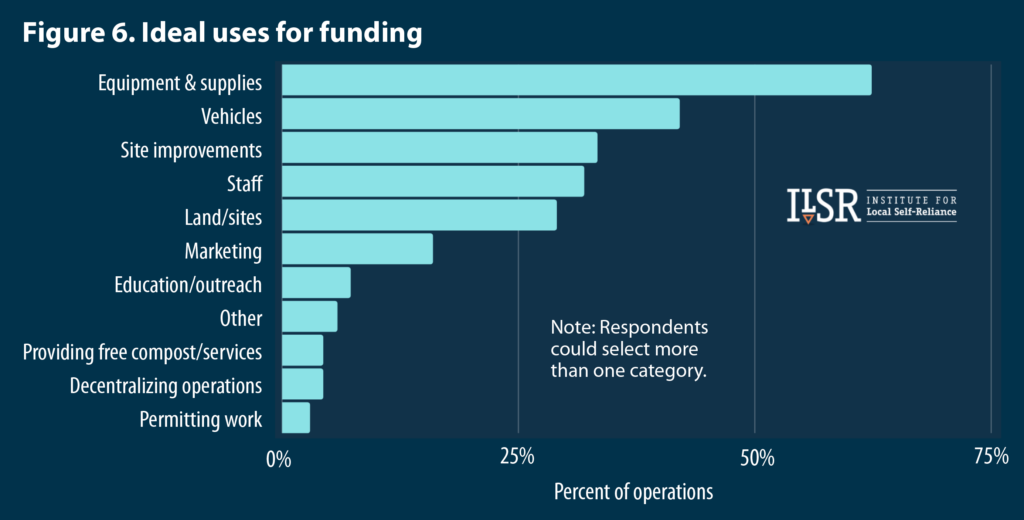

Despite these benefits, respondents report that policies surrounding composting often make it more difficult, not less, to run their program. To sustain or replicate operations like theirs, respondents call for regulation reform that creates allowances for small, decentralized, and/or start-up operations, as well as policies that prioritize rather than undermine community composting projects. In situations where community composters just starting up are struggling to handle large quantities of material and offer adequate benefits to their employees, partnerships with local government can provide contracts for services (e.g., curbside collection, servicing food scrap drop-off sites, Master Composter training programs) to make a larger, well-supported staff possible. To a question on what they would do with unfettered access to funding (Figure 6), one respondent replied, “Buffering startup payroll so that we can work full-time in getting our operation going and sustaining on its own (we both currently work other jobs to supplement our income). Also, paying for an office space in this startup phase.” Another respondent cited labor: “I would create well paying, life affirming jobs for marginalized communities.”

Getting this much-needed support will require recognition that investing in the community composting sector is much more than a waste management strategy — it comes with countless environmental, social, and economic co-benefits that amount to multiple community investment programs rolled into one. This first Census paints a picture of a diverse and dynamic array of operations with significant potential and increasing momentum. If community composters receive the same resources and attention as industrial operations from policymakers, equipment manufacturers, funders, and other key players, the numbers will continue to trend upwards.

Clarissa Libertelli is the Coordinator for the Community Composter Coalition, convened by the Institute for Local Self-Reliance’s Composting for Community Initiative. This Initiative is catalyzing decentralized local composting in order to cut food loss, enhance soils, support local food production, and protect the climate while addressing community prosperity and equity issues. This article concludes the 2-part article series from ILSR on ILSR’s report, A Growing Movement: 2022 Community Composter Census.