Top: Nursery trees are grown in a potting soil that contains compost. Photo by Ron Alexander

Craig Coker

It is now obvious that a systemic approach to developing source separated organics (SSO) programs is needed to increase diversion rates and quantities of feedstocks captured. The systemic approach involves careful consideration of diversionary strategies, collection options, processing technologies and end product usage plans. This article examines some of the barriers to end product usage, particularly for composts, and discusses market stimulation mechanisms at work today.

Types Of Compost Markets

Emerging new compost and soils markets with high potential include nonpoint source water quality management, illustrated above by installation of a compost filter sock for sediment control. Photo by Craig Coker

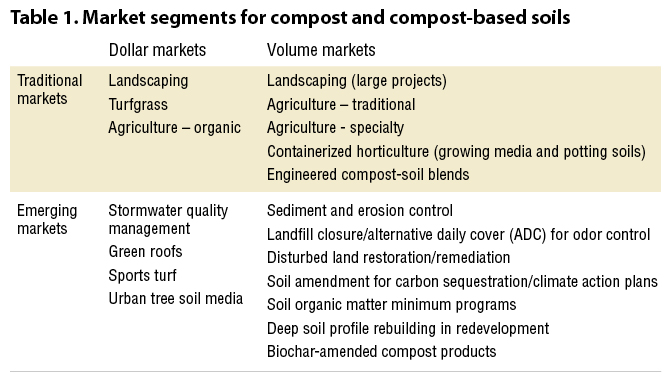

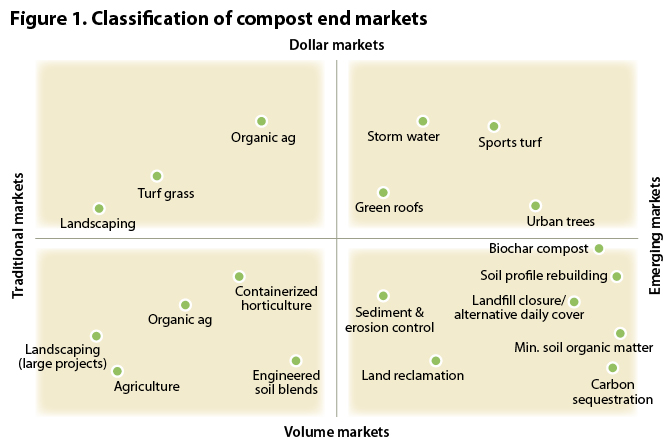

Market segments for compost and compost-based soil products can be classified as traditional and emerging. They also can be classified as “dollar” and “volume” markets (Tyler, 1996). Traditional markets are those in which a product is considered well-defined and has customers with well-developed buying patterns and established customer loyalty. The local residential and commercial landscaping markets would be considered traditional compost markets. Emerging markets are those in which the benefits of a product are still being defined. Emerging new compost and soils markets with high potential are in nonpoint source water quality management (i.e., rain gardens), sediment filtration and erosion prevention, low-impact development infrastructure, and in carbon sequestration/climate action plans. Examples of market segments are provided in Table 1.

Dollar markets can be described as those with higher unit price potential, but lower volume sales expectations. An example of a potential dollar market for compost would be residential landscaping and gardening. Conversely, volume markets are those with the capacity to support large product volumes but exhibit a lower unit cost and willingness to pay. Examples of volume markets for compost would be agricultural use or land reclamation/remediation. Similar distinctions are possible for compost-based soil products. Manufactured topsoil would be an example of a potential volume market, while sports turf growth media would be a potential dollar market. The distinctions between volume and dollar markets are not definitive, and potential compost markets can fluctuate between both dollar and volume depending on project size. For example, a small commercial landscaping job might be considered a dollar market but landscaping the grounds of a new shopping mall would be considered a volume market. Market segments are illustrated in Figure 1 below.

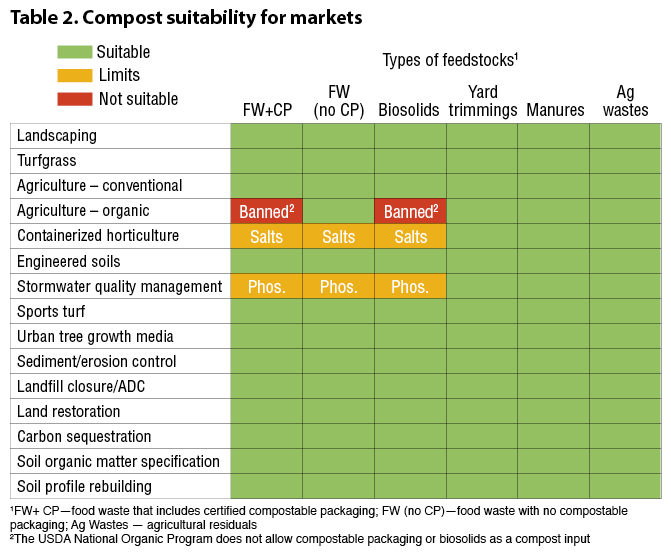

Suitability of various composts for various markets depends on the feedstocks processed. Six types are categorized: biosolids, yard trimmings, manure, agricultural wastes, food waste that includes certified compostable packaging, and food waste that does not include compostable packaging. Suitable end uses for these composts are shown in Table 2.

Barriers to Compost Market Development

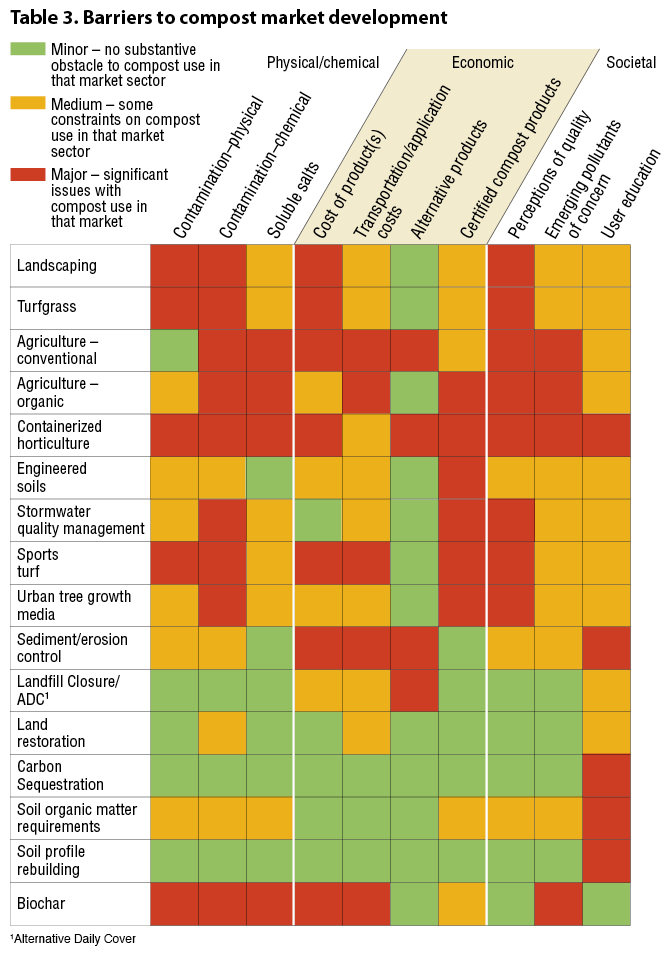

Barriers to compost market development can be classified as physical/chemical, economic and societal. These include:

Physical/Chemical

- Physical contamination: Non-compostable plastics, glass, metal, inerts

- Chemical contamination: Persistent herbicides, toxic chemicals

- Soluble salts: Problematic with food waste (FW) composts

- USDA National Organic Program (NOP): Rules for organic agriculture do not allow certified organic growers to use food scraps composts containing compostable plastics (viewed as made from synthetics); NOP also does not allow biosolids as an input

Economic

- Cost of product(s)

- Transportation and application costs; transport costs limit bulk compost distribution to about 50 to 75 miles

- Competition from less expensive alternative products, e.g., pre-seeded erosion control matting and fabric silt fence

- Certified compost products, such as the US Composting Council’s Seal of Testing Assurance (STA) program

Societal

- Consumer perceptions of product quality

- Lack of education of users by producers, e.g., need to educate engineers and architects about compost benefits in certain markets (Alexander, 2023)

- Emerging pollutants of concern not yet regulated (e.g., pharmaceuticals, PFAS, microplastics)

Certified compost products are an interesting example when considering market barriers. Small residential and commercial landscaping projects rarely require a certified product. For large volume commercial and government landscape projects (e.g., state Department of Transportation storm water management), however, the request for bids frequently requires an STA-certified compost that meets the project specifications. From a compost market standpoint, smaller compost manufacturers may not be able to afford the costs involved with securing and maintaining certification, so that requirement becomes a barrier.

Aspects of these barriers as they influence markets are presented in Table 3.

Market Stimulation Models

The impetus to recycle food wastes in the U.S. began to gather momentum following Vermont’s 2012 passage of Act 148 – the Universal Recycling Law, which banned disposal of all food waste by July 1, 2020. Today, nine other states (and 5 cities) have adopted various bans or restrictive laws on food waste disposal. But these legislative initiatives were enacted without corresponding legislation, policies or support for developing the processing infrastructure to handle the diverted organics and without legislation, policies and support for encouraging the use of recycled organic products, with the notable exception of California. In recent years, new initiatives to encourage the use of compost have been enacted. For the most part, these state and federal government initiatives incentivize greater use of compost in agriculture. A sampling includes:

- Urban Agriculture Grants: The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Compost and Food Waste Reduction Cooperative Agreements —a $9.5 million program for FY 2023 — support projects that develop and test strategies for planning and implementing municipal compost plans and food waste reduction plans in support of urban agriculture. Goals of the program include increased access to compost for agricultural producers, reduced reliance on chemical fertilizer, improving soil quality, and increasing rainwater absorption.

- USDA SARE Grants: USDA’S Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) program is a federal grant initiative supported by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture. SARE’s mission is “to advance innovations that promote profitability, stewardship of the land, air and water, and quality of life for farmers, ranchers and their communities.” Since 2016, the SARE program has provided $51 million of funding to 1,142 compost-related projects.

- Soil Conservation Standard: USDA/Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) Conservation Standard Practice 336 — Soil Carbon Amendment — was adopted in 2022 and covers application of carbon-based amendments derived from plant materials or treated animal by-products, including compost and biochar. The next step in the process is for states to adopt CSP 336 so more compost can be considered in conservation planning and made eligible for reimbursement through NRCS conservation programs. In states that have adopted CSP 336, incentive payments to farmers can be considerable. For example, in 2023, California farmers were eligible for reimbursement up to $270.21/cubic yard (cy) for compost produced on-site and up to $1,697.98/cy for compost procured from off-site.

- California Healthy Soils Program: The California Department of Food and Agriculture’s (CDFA) Healthy Soils Program (HSP) provides financial incentives to California growers and ranchers to implement agricultural management practices that sequester carbon, reduce atmospheric GHGs and improve soil health. A progress report released in 2021 found that using compost was the top healthy soil practice adopted by growers and ranchers. The HSP also funds on-farm demonstration projects that conduct research and/or showcase conservation management practices that mitigate GHG emissions and improve soil health. Since it began in 2017, CDFA has funded 1,600 projects with a result of reducing (through March 2023) 1.1 million metric tons CO2, and improved soil health on over 170,000 acres.

- Washington State Agriculture Incentive: The Washington State Legislature allocated grant funding in 2023 to reimburse Washington farmers for purchasing and spreading compost on their land. The Washington State Department of Agriculture (WSDA) launched the second year of the program in July 2024 with a new tranche of funding. The Compost Reimbursement Program (CRP) aims to encourage on-farm use of commercial compost. For eligible farms, the program pays up to 50% of the cost to obtain, transport, and spread compost, not to exceed $10,000/farm/year. Labor costs related to transporting and applying the compost and equipment purchased for transporting and spreading the compost are eligible expenses. The CRP also studies the benefits of compost application on soil quality. Participating farmers are required to collect and submit soil samples for several years from fields where compost was applied. Soil sample collection prior to compost application is required for participation. Changes to the CRP that take effect in 2024 include prioritizing applications based on the presence of food-waste feedstock in the compost to be purchased, as well as distributing reimbursement funding based on farm size.

Carbon Credits

Carbon credits were originally devised as a mechanism to reduce GHG emissions by creating a market in which companies can trade in emissions permits. Essentially, these credits create a monetary incentive for companies to reduce their carbon emissions. Those that cannot easily reduce emissions can still operate, but at a higher financial cost. Proponents of the carbon credit system say it leads to measurable, verifiable emission reductions. To date, there is no national carbon market. However, 11 states have adopted voluntary market-based approaches to reduce GHGs through a program known as the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI). Other voluntary programs, such as Indigo, focus on carbon credits for certain agricultural activities, such as converting to no-till, using cover crops and enhancing soil organic matter.

The impact of compost on carbon emissions can be recognized in a number of ways. On a broad scale, these include regulatory changes, protocols on carbon markets, and activity by companies or organizations (Brown, 2021):

- Food waste disposal restrictions: A landfill diversion ban is a legal mechanism to reduce emissions. In jurisdictions covered by a disposal ban, participation in voluntary carbon markets is no longer possible as the carbon markets view awarding credits where GHG emitting activities are restricted as double-dipping.

- Compost use, procurement: Where requirements exist for compost use, e.g., post-construction soil organic matter mandate, it is unclear at present whether those usage projects would be eligible for carbon credits.

The three voluntary carbon markets in the U.S. are the Climate Action Reserve (CAR), the American Carbon Registry (ACR) and Verra. It is recognized that a national Carbon Credit market that will have meaningful impact on compost sales is many years away.

CAR adopted a Soil Enrichment Protocol in May 2022 which provides guidance on how to quantify, monitor, report, and verify agricultural practices that enhance carbon storage in soils. The primary GHG benefit targeted is the accrual of additional carbon in agricultural soils, with hopes to incentivize GHG emission reductions from other sources, such as nitrous oxide from fertilizer use. To qualify, soil enrichment projects “must be located on land which is, as of the project start date, cropland or grassland (including managed rangeland and/or pastureland), and which remains in agricultural production throughout the crediting period. Projects shall not include areas which have been cleared of native ecosystems or other restored or protected areas (i.e., restored grassland) within the 10 years prior to the project start date. Project activities must not decrease carbon stocks in woody perennials on the project area. Projects should not introduce broadscale organic amendments to grasslands, because of the potential to shift systems towards lower grassland biodiversity, by excessively increasing nutrients in the system.”

ACR had a soil enrichment protocol for compost additions to grazed grasslands, but it was declared inactive and ineligible for carbon credits. ACR has determined that the methodology requires updates to measurement, monitoring, reporting and verification requirements to be consistent with the current version of the ACR Standard.

Soil Improvement Mandates

Compost engineered soils for rain gardens and other green infrastructure applications are an example of a high dollar, lower volume market. Photo by Craig Coker

Several regional and local programs have been adopted to improve storm water runoff quality that promote compost use to meet the program goals and objectives. These have been reported on in BioCycle for many years (McDonald et al., 2007; Ceransky, 2014, Coker, 2021). Two examples include:

- Soils for Salmon: The Washington State storm water manuals and local codes require 3 inches of compost to be tilled 8 inches into the soil for planting beds, and 1.75 inches of compost tilled in 8-inches deep for turf areas. (Alternatively, a “calculated rate” can be used to meet the organic matter content requirements, which are 8 inches of settled soil at 10% organic content for planting beds, and 5% organic content for turf.) The soil must be scarified an additional 4 inches to achieve a total depth of 12 inches of uncompacted soil after the calculated amount of amendment is added. Scientific trials in Washington and elsewhere have shown that these simple soil BMPs can reduce storm water runoff by 50% or more, and reduce the summertime need for landscape irrigation by 50% — which pays for the amendments in three to five years.

- Soil Profile Rebuilding Program: Arlington County, Virginia adopted a Soil Profile Rebuilding (SPR) specification developed by Virginia Tech. The county is a densely developed suburb of Washington D.C. where around 200 individual one-story ramblers built in the 1950s and 1960s are torn down and replaced with larger, multistory homes every year. This rebuilding process compacts the soils around the replacement homes, leading to increased storm water runoff, with attendant impacts on the water quality-impaired Chesapeake Bay. The County issues Land Disturbing Activity permits for these residential rebuilds and starting in September 2021 requires permittees to have more rigorous storm water runoff controls. All permittees are required to decompact their soils and use soil amendments to restore essential soil functions to absorb rainfall and runoff and support grass, tree, and other plant growth following the procedures of the SPR.

Several western U.S. communities have adopted irrigation water demand reduction programs, which require amending the soil with compost. Soil scientists report that for every one percent of organic matter content, the soil can hold 16,500 gallons of plant-available water per acre of soil down to one foot deep. That is roughly 1.5 quarts of water per cubic foot of soil for each percent of organic matter. Increasing the organic matter content from one to two percent would increase the volume of water to 3 quarts/cubic foot of soil (Gould, 2015). By increasing the water-holding capacity of soils with compost amendments, the amount of rainfall that infiltrates into the soil is increased, the amount of runoff produced by rainfall decreases, and decreased runoff quantities are positively correlated with decreases in runoff pollution concentrations (Glanville, 2002).

Shorter-term programs to stimulate compost markets might include:

- Expand the concepts behind the California and Washington agricultural compost use incentive programs to residential compost use in ornamental beds, vegetable gardens and turfgrass by reimbursing residential users who submit valid, verifiable receipts for compost purchases.

- Encourage the adoption by state and/or local governments to require a minimum soil organic matter content for all new development to reduce demand for irrigation water and to reduce pollutants associated with storm water runoff.

- In a similar vein, encourage local governments to adopt soil profile rebuilding requirements in their building permit programs to reduce water demand and storm water runoff.

Compost manufacturers cannot take it for granted that the compost they make will automatically be absorbed by markets at a fair price. Marketing efforts should be focused on tailoring the products to the appropriate markets and campaigning for state and local governments market incentives.

Craig Coker is co-owner of Star City Compost LLC in Roanoke VA, a senior editor at BioCycle Connect, and CEO of Coker Composting and Consulting. He can be reached at ccoker@cokercompost.com. Several graphics and portions of the article text originally appeared in Unleashing the Economic and Environmental Potential for Food Waste Composting in the U.S., A Guide For Investors, Policymakers And The Compost Industry, released in July 2024 by the Center for the Circular Economy’s Composting Consortium at Closed Loop Partners.