Craig Coker

The financial considerations related to starting, operating and/or expanding a composting facility — covered in Parts I-IV in our Compost Business Management series — are essential to understand and master. At the same time, there is a trend to assess nonfinancial considerations that might influence decisions. These types of analyses are referred to as “People, Planet and Profit,” also known as triple bottom line analyses.

Triple bottom line (TBL) analysis uses economic, environmental and social criteria to answer the question: “Is this [project or program] a good long-term investment?” It breaks down economic, environmental, and social evaluations into criteria and sub criteria that are both qualitative and quantitative. These criteria can then be weighted based on local contexts and applied to feasibility studies. Accounting for the impacts of each criterion over the project life cycle is important for a complete analysis. TBL analyses can be used to compare project alternatives, as well as to decide whether to move forward on a project or not.

Selecting Criteria

To select criteria for TBL analysis:

- Identify criteria that meet all requirements for sustainability.

- Ensure that the criteria are clearly defined and understood by all stakeholders.

- Develop a ranking system and weight system for the criteria to aid in the decision-making process.

- Include “upstream” and “downstream” impacts of choices made (i.e. technology choices) which are “directional, concise, complete and clear” (Jones, 2019).

A methodology similar to TBL is called the Weighted Criteria Decision Matrix, a decision-making tool used to evaluate alternatives based on specific evaluation criteria weighted by the importance of each criterion. This tool can be used to do a TBL analysis. Each alternative is scored against each evaluation criterion on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 = did not meet the criterion well, 3 = met criterion fairly well, and 5 = meets the criterion very well. For example, if buying an automobile, one evaluation criterion might be fuel economy. An alternative vehicle with an estimated fuel economy of 36 miles per gallon (mpg) would score around 4 or 5 (decimal scores, e.g., 4.3, are possible with this methodology) while one with an estimated fuel economy of 19 mpg would score around 1 or 2. This scoring methodology is inherently subjective for most criteria and is heavily dependent on the accuracy of the information supplied for this process.

The score of each alternative against each evaluation criteria (known as the “raw score”) is then multiplied by the weighting factor for that criterion. Weighting factors are also assigned on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 = criterion is not important at all, 3 = medium importance and 5 = extremely important. Different stakeholders assigning weighting factors may have different perspectives of importance, so differing weighting factors are averaged before applying them to the evaluation criteria. For example, a family of four considering buying a new car might give “engine horsepower” weighting factor scores of 3.5, 2.5, 4.8 and 3.9. The average weighting factor for that evaluation criteria would be 3.675.

The stakeholder-average weighting factors are multiplied by the raw scores for each evaluation criteria to arrive at a weighted score for each criterion. Weighted scores are then summed for each alternative to arrive at a total weighted score. The alternative with the highest weighted score is the preferred alternative.

By evaluating alternatives based on their performance with respect to individual criteria, a value for the alternative can be identified. The values for each alternative are then compared to create a rank order of their performance related to the criteria as a whole. This tool is important because it treats the criteria independently, helping avoid the over-influence or emphasis on specific individual criteria. The evaluation criteria should be developed by the staff, with input from stakeholders; the importance of weighting factors should be assigned by management.

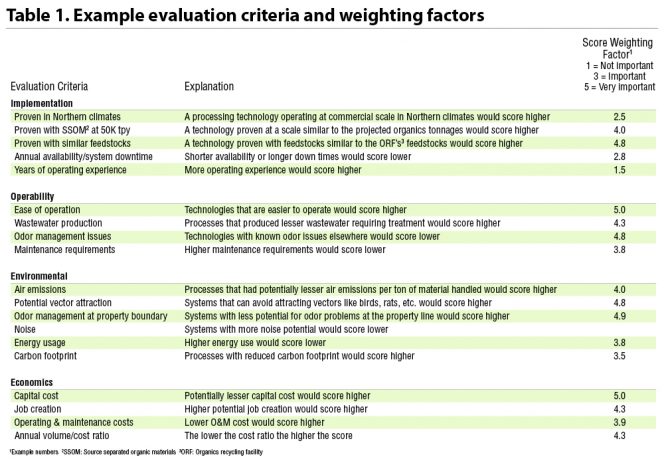

Composting Example

Table 1 illustrates use of this tool to evaluate alternative composting approaches for a large-scale source separated organic materials composting enterprise in the upper Midwest. Evaluation factors were developed in categories of Implementation, Operability, Environmental and Economics. For example, one Implementation-related criterion was Proven with Similar Feedstocks, where demonstrated use of the composting technology with similar feedstocks would score higher. The management of the composting enterprise felt that criterion warranted a weighting factor of 4.8 out of 5. Under Operability, the criterion was Maintenance Requirements, where higher maintenance requirements would score lower. That criterion was assigned a weighting factor of 3.8.

For a more in-depth discussion of this analytical approach, read “Weighting Factors In Organics Recycling Facility Development.”

For a more in-depth discussion of this analytical approach, read “Weighting Factors In Organics Recycling Facility Development.”

Series Summary

This Compost Business Management series reviewed several financial tools, procedures and approaches, along with procedures and approaches for assessing non-financial considerations that composters can use to evaluate their options for a new facility, for new equipment, for expanding or for whatever reasons they choose. These tools help guide you through the age-old adage, “Proper prior planning prevents poor performance”.

Craig Coker is a Senior Editor at BioCycle and CEO of Coker Composting & Consulting near Roanoke, VA.