Craig Coker

There are numerous issues to evaluate and decisions to make if you are going to open a new, or expand an existing, composting facility — or grow into a second or third site. This 5-part series of articles will give you tools to organize these analyses efficiently to make sound decisions. Financial topics to be covered include revenues, capital costs, operating costs, net present values, and cash flow pro formas. The series also will provide methods for evaluating nonfinancial factors such as environmental and social impacts, job opportunities, and implementation realities.

While composting is certainly a more environmentally conscious means of handling biodegradable materials, the simple reality is that everything revolves around costs. It is necessary to learn how to estimate costs and revenues, evaluate different alternatives on the basis of their long-term costs, and assess the impacts of costs on cash flows and budgets. While this series is tailored towards private sector composters, these methods apply just as well to public sector facilities.

Part I covers the revenue side of composting. Forecasting revenues is needed to support bank loan requests or for seeking money from equity investors. Forecasts should be made on a 3- to 5-year basis. The composting industry is unique in the American business landscape as facilities can earn revenues from both incoming feedstock processing fees and outgoing product sales. Plus there are ways to bring in revenues from collecting feedstocks and delivering products along with vertical integration into related areas like contract grinding and/or contract bagging.

Processing Fees

Feedstock processing fees are also called “tip” fees, a term coined by the landfill industry to reflect a fee for “tipping” garbage into a landfill. In the composting industry, a more appropriate term is gate fee or processing fee.

In states or communities with bans on landfilling organics, your processing fee should be calculated on the basis of what it costs you to make a cubic yard of compost (we’ll discuss how to make that calculation later in this article). If you are not in a state that bans organics from landfilling and your facility is, or might be, located within 50 miles of another composting facility taking in feedstocks for a fee, then your processing fee could be discounted to attract customers away from your competitor.

If no competitor is nearby, your most likely competitor for solid feedstocks is the local landfill or transfer station. In this case, you want to set your processing fee at least at a 10% discount to what the landfill or transfer station charges, in order to create a financial magnet to pull feedstocks away from solid waste disposal and into organics recycling. Keep a close eye on your production costs, though, as you will have to make up for the impact of the discount in your product sales revenues.

If you have the ability to handle liquids, such as food processing plant process sludges (not biosolids), then your competition is likely a land application contractor, where land application costs are in the $15 to $20/ton range but who is more subject to weather interruptions than the composting facility. These types of industrial contracts are favored, as the feedstocks are very clean and contract terms can be as long as 5 or more years, but as contract length increases, expect downward pressure on your processing fee, which is another good reason to really know your processing costs.

If you want to take in biosolids, focus on what it is now costing the wastewater treatment plant to recycle or dispose of their biosolids. Often, biosolids disposal/recycling contracts are public bid events, so lowest responsible bidder will usually prevail. If you bid on these types of contracts and have to bid low to win, recognize it may be more difficult to make up the revenue shortfalls on the product sales side.

Compost And Soils Sales Estimates

Compost and soils sales estimates are more difficult to project, as factors such as your distribution model (retail, wholesale or both), presence (or absence) of competition, “eco-friendliness” of the demographic in your 50- to 75-mile market zone, and diversity of markets can all affect pricing and sales. A good way to start is by mystery shopping at every retail and wholesale outlet in your market zone to gather intel on what is being sold and at what price point. If you are well known in your community, you may ask friends and family to do the intel gathering using a prescribed method. Based on your assessment of the strength and market share of competition, you can make reasonable assumptions about how much market share you will be able to capture in the same 3- to 5-year forecast window.

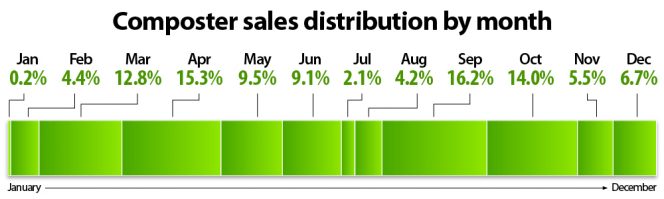

If you are currently selling compost, keep track of how much you sell each month (as a percent of annual totals) as this data can be used to forecast sales in cash flow pro formas (discussed later). If you are not selling yet, you can use the approximate percentages shown in graphic, adjusted for your seasonal variations. The data in Table 1 is from a mid-Atlantic municipal yard trimmings composter.

Revenues from trucking feedstocks in, and delivering product out, can be significant. One composter I work with has a fleet of 8 tractors and 30 trailers, billing out feedstock hauling and product delivery at $100/hour where his cost is $70/hour. In more congested areas where travel time is more important than travel distance, use Google Maps to estimate travel time and base delivery fees on the multiple of travel time, and hourly labor rate plus collection/delivery vehicle machine rate. In more rural areas, you can use a per mile factor of $4.50 to $5.00/loaded mile.

Contract grinding and bagging services can be a revenue source for composters. Photos by Doug Pinkerton

Related Services

Another area of revenue potential is diversifying into related business practices. For example, if you are going to invest in a grinder for particle size reduction of your carbon bulking agent, consider diversifying into contract grinding of yard trimmings, clearing debris and/or storm debris in your market zone. While these are normally competitively-bid projects and there is a great deal of low price competition, winning these bids helps secure a source of carbon bulking agent and can provide extra trucking revenue. Another diversification could be using bagging equipment to not only bag for your product lines, but to provide contract bagging for others offering noncompeting products like mulches.

Craig Coker is a Senior Editor at BioCycle and CEO of Coker Composting & Consulting near Roanoke, VA.