Top: Baby Hudson models a traditional disposable diaper

Sally Brown

Sally Brown

Since the time compostable diapers first became a goal of the industry, many of us have progressed from buying Pampers for our kids to Depends for ourselves. Compostable diapers are where it all began. Back in the day (1990) Proctor & Gamble (P&G) effectively kickstarted the compost industry by creating a $20 million research fund to look at, in part, the potential for compostable diapers. It was because of diapers that the US Composting Council (USCC) was formed (originally called the Solid Waste Composting Council).

In many ways this is a concept that makes absolute sense. The high carbon absorbent portion of the diaper married with the high nutrient and moisture content of #1 and #2 make a perfect feedstock combination. You pair that combination with parents who want to do everything to make sure the world is a better place for their newborns and what could go wrong? This is the point in the column where readers in the know start shaking their heads. “So much,” they say.

Chlorine-free and made with organic cotton are among the more “natural” offerings on retail store shelves.

Disposable diapers, and here I am just talking about the ones for babies, are a big deal from multiple angles. A recent study from the European Union (EU) points out just how big (Mendoza et al., 2019). In the EU, 21 billion diapers are used each year at a cost of about 4.2 billion euros. This requires 700 kilotons (700,000 tons) of raw materials. Disposing of these diapers amounts to the MSW equivalent of a city of 1.4 million people and emits 2.7 Metric tons (Mt) of greenhouse gasses. Diapers are just part of a category of products that in theory are all excellent composting feedstocks. This category includes feminine hygiene and incontinence products. In other words, products that carry us from cradle to grave. Unfortunately, very little progress has been made in lowering the carbon impact of this journey.

I came into the compost world after the first flush of cash for research on compostable diapers had been spent. When I was in graduate school, the big diaper conversation at the U.S. Department of Agriculture was about using chicken feathers to make the soft, carbon based portion of the product. Now when you do a search for diapers and chickens you get results for diapers for, rather than from, chickens. In other words, that innovation didn’t quite fly. The big innovation since those heady days of available funding for compostable diapers is the Diaper Genie. This product fits right into the nursery, comes in a variety of colors, has a carbon filter to take away any potential odors and squishes the diapers into a plastic bag that makes the trip to the black bin absolutely painless. In other words, diapers have gotten more convenient to toss but little has changed in terms of alternatives to the trash. In our world where food waste collection is approaching the everyday norm, this seems like the next obvious goal. But apparently, not everybody thinks the way that I do.

Diaper Innovations

There have been some innovations in diaper manufacture. If you think about it, diapers are the kid equivalent of toilet paper and I recently talked about what an impact bamboo or recycled toilet paper can have. Reducing the footprint of manufacturing in terms of virgin material use and process efficiencies can have a big impact. For example, the cellulose component of diapers is enhanced by superabsorbent polymer (SAP) and making SAP from recycled materials would reduce the environmental impact of the diapers (Lacoste et al., 2019). It turns out that a key component of SAP is carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC). Different materials have shown promise. It may be that in the future the CMC for the SAP is made from recycled newspapers, office papers, corn husks, cardboard, and cotton gin waste. It seems that the concept of using chicken feathers has flown the coop.

Another study I looked at considered ways to make the diaper without the glue (Mendoza et al., 2019). It turns out that you can use thermo-mechanical and ultrasonic bonding in place of glue. Doing so saves money and makes for a lighter weight (fresh not full) diaper. This in turn reduces the life cycle cost and impact of the diaper. All good but the authors of the glue replacement paper conclude the following:

“Nevertheless, product light-weighting (e.g. material optimisation of the absorbent core through eco-design) and cleaner production (e.g. use of alternative bonding technologies) will not resolve the critical underlying issue of linear material consumption and waste generation associated with the diapers. …. The authors consider that the application of nature-inspired circular economy approaches would not only bring novelty in the development of sustainability-oriented studies for the absorbent hygiene industry as a whole, but also provide relevant insights for future industrial innovations and development of strategic corporate sustainability plans.”

In other words, right back to those heady days of (P&G) and the compostable diaper. I am occasionally asked about the potential for compostable diapers — is this a product that would have consumer appeal? I always enthusiastically say “Yes!” I was most recently asked about this at the USCC conference in Austin. A woman who works for a large German company that specializes in adhesives was the one asking. Apparently, she hadn’t read the paper about the glueless option. She is tasked with identifying areas for footprint reduction. We had a great conversation and I referred her to a municipal solid waste person and a composter to get their feedback. The response from the composter was a resounding “no thank you!”:

“We have heard opposition from composters about this type of product, due to mainly contamination concerns (from non-compostable look-alikes). Because of these concerns and our focus on the bigger portions of the waste stream, this is not a priority for us at this time, and I am not sure what direction we could offer….”

The other was much more pleasing to my ears:

“I …. do not know of anyone who will take diapers because of the untreated human waste issue. I am happy to explore with her and even speak with the state as it would be great to get a program with compostable diapers in CA and beyond.”

Compostable Diapers

I also did a search to see if compostable diapers were available. There were none in my local supermarket. On line I found many listed that are not compostable but that contain fewer objectionable ingredients. Bamboo is now a key ingredient in some of these products, meaning that the environmental impacts of making the diapers is reduced. The ones that are compostable/ biodegradable are not suitable for home systems but require full scale municipal systems that reach time and temperature requirements for pathogen kill to fully decompose. One had compostable components but also portions that do not degrade.

This gets us to the reason that the last person who approached me on this was a glue expert. Diapers have evolved from the time of cloth nappies with safety pins. This evolution has been guided to assure a more pleasurable experience for the wearer and the changer. No leaks with the plastic outer layer in combination with some type of elastic to assure a perfect seal. No pricks with safety pins replaced by pull and stick fastening. A range of additives to promote absorbance and reduce the potential for diaper rash. This translates into a complex system where multiple parts have to work together to keep the tush dry but still degrade.

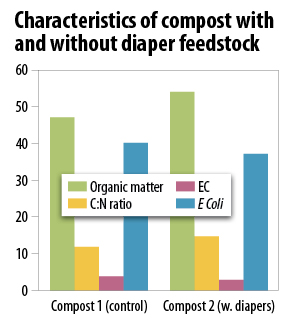

I checked in the literature to see if these complex diapers that claim to be compostable actually are. A study done within the last 10 years, so within the time that diapers that they tested looked a lot like the diapers you can purchase now, was the best I found. Colón et al., (2013) looked at full-scale composting of diapers as a component of the organic fraction of MSW. In the introduction the authors have a few more interesting diaper facts. After weighing over 600 of them, they conclude that the average soiled diaper weighs 212 g or just under half a pound. The authors also note that day care centers and nurseries are great places to test compostable products. (Any diaper manufacturers reading this should note that fact for future pilot studies.) For their trial, they outfitted kids in two nursery schools with two brands of compostable diapers for 11 days. Seventy-five kids and 1,100 diapers later, the soiled diapers were mixed with household organic waste at a commercial scale municipal composting facility. The facility used a static pile system with forced aeration. Cut to the chase — they composted just fine. In fact, the authors present characteristics of the compost with diapers and the compost without them (the control). Can you tell which is which in the figure?

I checked in the literature to see if these complex diapers that claim to be compostable actually are. A study done within the last 10 years, so within the time that diapers that they tested looked a lot like the diapers you can purchase now, was the best I found. Colón et al., (2013) looked at full-scale composting of diapers as a component of the organic fraction of MSW. In the introduction the authors have a few more interesting diaper facts. After weighing over 600 of them, they conclude that the average soiled diaper weighs 212 g or just under half a pound. The authors also note that day care centers and nurseries are great places to test compostable products. (Any diaper manufacturers reading this should note that fact for future pilot studies.) For their trial, they outfitted kids in two nursery schools with two brands of compostable diapers for 11 days. Seventy-five kids and 1,100 diapers later, the soiled diapers were mixed with household organic waste at a commercial scale municipal composting facility. The facility used a static pile system with forced aeration. Cut to the chase — they composted just fine. In fact, the authors present characteristics of the compost with diapers and the compost without them (the control). Can you tell which is which in the figure?

While compostable plastics and adhesives make this possible in an ideal world, in the real world the problem then becomes how do you tell which are which? Is this the compostable diaper or the conventional diaper? At the composting facility the specter of the compostable diaper translates into more headaches re: sorting and separating, much the same as we see with plastic utensils and containers. If all of the traditional diapers were to magically go away so that only compostable were available, it would be one thing. But in our universe that is a near impossibility. Over time and with appropriate pressure from regulators and cooperation (diversifying compostable options) from manufacturers, it might happen. Making a special diaper genie that would scan and only accept the compostable versions and bag them as such might be one option. Until this magic happens though, we are right back in the time before P&G all over again.

Sally Brown, BioCycle Senior Adviser, is a Research Professor in the College of the Environment at the University of Washington.