Sally Brown

BioCycle August 2019

I distinctly remember the first time I saw maggots in action. I was visiting my friend Cheryl. While Cheryl had a wicked sense of humor, her housekeeping left a bit to be desired. She opened the oven door and this churning mass of white things had taken over the dinner that she had forgotten about days before. It was disgusting.

Time and knowledge can really change one’s perspective. Now when I see maggots (fly larvae), I see the potential for a big solution. Those contaminants in food scraps that plague composters? The maggots don’t mind a bit. Those dead fly larvae? May be disgusting to you but feed them to a fish or a chicken and you are talking finger licking good. Under certain conditions and using the appropriate type of fly, this method of food waste stabilization can provide solutions to multiple problems in a cost-effective manner.

Flies live and die quickly. It is only at the end of their lives that they actually look like flies. The female lays eggs, generally several hundred at a time. After a few days the eggs hatch as larvae. These larvae start out invisible to the eye (1 mm long) and after about 20 days, can grow up to 2.7 cm long. Then they stop eating and get ready to transform. This pupal stage is a week or two, after which the wings come out and you know what you are looking at when you see one. Adult flies can last for 1 to 2 months.

It is the larval stage that I saw in Cheryl’s oven and that is pertinent to organics. There are different types of flies with different eating preferences, life spans, and potentials. For pig manure you want one kind. For half empty ketchup wrappers you want black soldier flies (Hermetia illucens).

Black Soldier Flies

These black soldier flies are fussy about certain environmental conditions. They prefer warmer temperatures (about 30°C), like their food moist but not anaerobic. They don’t like too much zinc or other heavy metals in their diet, but glass and plastic don’t bother them one bit. In other words, typical food waste, with typical contaminants can keep thousands and even millions of fly larvae happy. If only they could, these guys would give food waste the highest rating possible on YELP. And talk about appetite — for each wet kilogram of food scraps (not counting the plastic wrappers), you get close to a 12 percent yield in fly biomass with 32 percent remaining as residue. While not quite wild caught King Salmon or filet mignon, these prepupal flies are 43 percent protein and 28 percent fat. You can eat them directly (I have), however the thought of feeding them to fish, chicken or pigs is much more appealing.

Black soldier flies come with challenges. They don’t like their food piled too deep. About 7 to 10 cm (3-4 inches) is a good depth. Standard aeration is also not the best option to keep things from going anaerobic. The food scraps dry out too much to be palatable near the air holes. Also, the flies like to lay their eggs in the holes, creating clogs. Turning the larvae and the scraps may be the best approach to maintaining the proper ambience to encourage gorging. It is also not clear how to best scale up a fly restaurant to treat high tonnages of food scraps. Coming up with the best all you can eat buffet is a challenge still facing this approach.

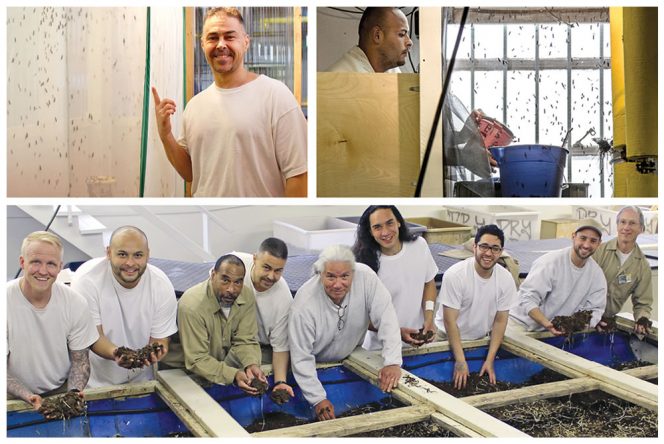

Lead technician for the BSF program shows adult flies in an updated enclosure (top, left). Photo by Erica Benoit

A technician attends to adult black soldier flies (BSF) in their enclosure (top, right). Nearly all sorted food waste at Monroe Correctional goes to the BSF. Photo by Ricky Osborne

Technicians lined up at processing bins at Monroe Correctional Complex’s worm farm explain how sorted food waste (fruits and vegetables) is processed by red wigglers (bottom). Photo by Erica Benoit

Imagining The Potential

Despite these challenges, think of the potential. If we re-envisioned food scraps recycling, at least in part to include black soldier fly consumption, the issue of contaminants can largely be ignored. At least it would not present an obstacle that shuts down programs. In addition, we get to skip the soil part (can’t believe that I just said that like it is a good thing) and produce animal feed directly from the waste materials. A life cycle assessment concluded that producing animal feed from fly larvae fed on municipal solid waste is a much more environmentally friendly option in comparison to traditional livestock farming and feeding. Cities could be making food for poultry and aquaculture with their food scraps. The remaining material after feeding the flies could be composted or even landfilled. The pupae from the flies is a marketable product that could be sold regionally. This type of operation would also employ people. Breeding and raising flies is not a high tech endeavor, but is estimated to require some labor and supervision.

Compost technicians on their program at Monroe Correctional Complex from SustainabilityIn Prisons Project on Vimeo.

The black soldier fly operation that I have actually seen in person is at the Monroe Correctional Facility in Monroe, Washington. The inmates there have a vermicompost operation that has been written up in BioCycle on multiple occasions (“Science + Prisons Create Innovative Solutions“, “From Drugs To Bugs“). You can watch a video clip of the whole operation (above) including the flies. It looks nothing at all like Cheryl’s kitchen with one exception: If you time the visit right, just after the larvae have been fed, you get that same writhing, frantic feeding action that I first saw in Cheryl’s oven. Here though, it is in a clean, controlled space. Take it out of the oven and put it in a bin and it quickly transforms from revolting to riveting. The program at Monroe Correctional just got a pulper so the quantity of food scraps fed to the flies can be increased. Hopefully, these guys can be trendsetters for other food scrap operations. It just might be a real solution for both waste treatment and sustainable food production. s

Sally Brown is a Research Professor in the College of the Environment at the University of Washington. She authors the Connections Column in BioCycle, and is a member of BioCycle’s Editorial Advisory Board.