Top: Toby Una, who assisted in the research trials, at one of the plots. Photos courtesy of Sally Brown

Sally Brown

Sally Brown

Compost makes everything better. Very often that is true. Sometimes it isn’t. A few years ago, I had this great idea for a study. Test compost (and other soil amendments) side by side against chemical fertilizer in urban gardens. I was sure that the amendments would make the soil healthier and give you more and healthier vegetables. I thought that the same way that organics heal the soil, they would yield even healthier kale (if such a thing is possible). The answer was not a resounding yes, more of an “it depends.”

We set up the field portion of the study at three sites. Each had a history of amendment use, enabling us to compare the impacts of long-term use of amendments to newly fertilized soils. At each site fertilizer was added to fresh soil at rates of 178 kg/ha for each of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium (NPK). One site was the prison in Monroe, Washington. Inmates had set up a great program where food scraps were turned into vermicompost. The prison has a garden where a wide range of vegetables are grown. In between two old brick structures and surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards, this seemed like an extreme version of an urban setting. The second site was at City Soil Farm on the grounds of a wastewater treatment plant in Renton (WA). City Soil Farm is used for demonstration and outreach as part of the King County (WA) Wastewater Division’s educational program. The plant and farm are right near a big mall and two major highways. The final field site was at the Tacoma (WA) wastewater treatment plant. We used an area that had been a demonstration garden for years and another area planted in shrubs as the control. The delivery trucks and customers’ vehicles drove between the two sets of plots with the train tracks just outside the gates.

At each site, the locally produced amendments were tested next to the chemical fertilizer. For Monroe that meant vermicompost. At City Soil Farm we used a biosolids compost, made from biosolids from the plant and sawdust. In Tacoma we used Tagro potting soil, a mix made from biosolids, aged wood, sawdust and a little sand. A range of vegetables were grown over two seasons. Broccoli and carrots for both seasons and kale, and Swiss chard for the second season. A range of soil properties were measured, including bulk density, total carbon and nitrogen, water infiltration rates, available nutrients and POX-C- (an extract used to estimate carbon available for microbial activity). For the plants, we looked at yield and also nutrient concentrations. We had hoped to look at vitamins and some exotic phytochemicals, but then COVID hit and labs shut down.

The field plot in Tacoma showed robust kale yield in the row amended with the Tagro biosolids product.

Field Trial Results

What happened in these trials wasn’t clear across the board, i.e., providing hands down proof of the universal superiority of organic soil amendments. You know how they say in ads that “results may vary”? Well, it turns out that the same is true for soils and vegetables. I’ll start with the soils.

At Monroe, there were a number of complications. The biggest one was the fact that a few years before we got there, a big truckload of manure had been brought in to establish the garden. The soil, despite the barbed wire and guard tower, was pretty rich. The same was true at City Soil Farm. The soil hadn’t been disturbed by construction or much of anything else. It was an alluvial soil, having received sediment from the nearby Green River. These are some of your most fertile soils. At Tacoma, it was night and day. The soil was likely subsoil dug up during construction of the plant.

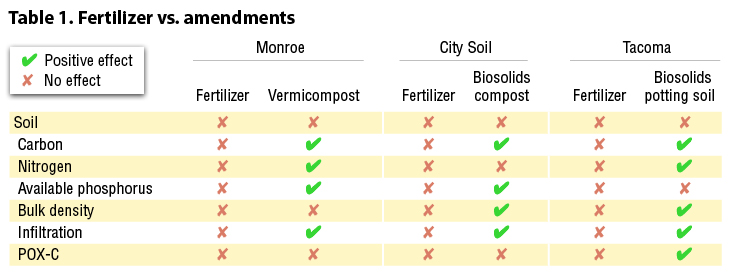

For all sites, the amendments made most things better in comparison to the fertilizer. In no case did the fertilizer make anything better than the amendments. The magnitude of the improvements varied by site. The least impact was seen at City Soil Farm where the compost increased total carbon and available phosphorus, lowered bulk density and increased the infiltration rate. At Monroe, the vermicompost increased carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus but showed no impact on bulk density or POX-C. It made a modest improvement in the infiltration rate for the second year of the trial. Tacoma was the shining star — the Tagro made everything a lot better with the exception of available phosphorus. Table 1 summarizes the findings.

The soil results were a dream come true in comparison to the plants. At both the Monroe and City Soil Farm sites, for most of the plants we grew, yields were better in the fertilizer than in the amended soils. The best I can say for the amendments was that for some of the vegetables in one or both of the years, yields were statistically similar to the fertilizer. Almost as good was not what I was hoping for. In contrast in Tacoma, there pretty much was no yield in the chemically fertilized soils. Grow those plants in the Tagro and they get big enough you can invite the whole family for dinner. The response as far as nutrients was also hit and miss. I can’t tell you the results from Tacoma as it is impossible to compare the nutrients in the control to the Tagro when there wasn’t anything to analyze in the control. At the other sites, there was no consistent pattern across the vegetables we grew and the nutrients we measured. One nutrient would be higher in one vegetable in the amended versus the control but another would be lower.

The soil results were a dream come true in comparison to the plants. At both the Monroe and City Soil Farm sites, for most of the plants we grew, yields were better in the fertilizer than in the amended soils. The best I can say for the amendments was that for some of the vegetables in one or both of the years, yields were statistically similar to the fertilizer. Almost as good was not what I was hoping for. In contrast in Tacoma, there pretty much was no yield in the chemically fertilized soils. Grow those plants in the Tagro and they get big enough you can invite the whole family for dinner. The response as far as nutrients was also hit and miss. I can’t tell you the results from Tacoma as it is impossible to compare the nutrients in the control to the Tagro when there wasn’t anything to analyze in the control. At the other sites, there was no consistent pattern across the vegetables we grew and the nutrients we measured. One nutrient would be higher in one vegetable in the amended versus the control but another would be lower.

Greenhouse Trial

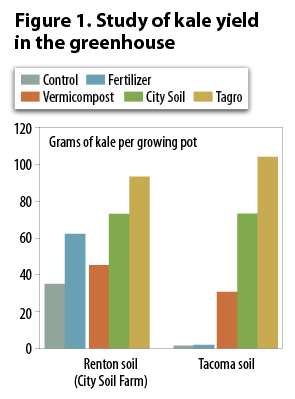

One of the flaws with the field trials was that we weren’t able to test each of the amendments at each of the sites. Each had been selected because of the long-term history of amendment use. Adding a whole lot of material to new plots would have created flaws in the study design. Plus, it was hard enough getting the prison to let us in to do the work; no way we would have been allowed to bring in buckets of compost. As a way to solve this, we set up a greenhouse trial. Enough soil was obtained from Tacoma and City Soil Farm to use those as controls. We were able to get vermicompost from the prison. Each soil had the full range of amendments added that we had used in the field trial. For this study a control soil with no fertilizer added as well as the fertilized control were used. Kale was the chosen crop.

Here the results made much more sense (Figure 1). For the plants grown in the Tacoma soil, all of the organic amendments made a huge difference. Kale Caesar versus no Kale Caesar. Portion size varied by amendment. The highest yield was in the vermicompost — the very same amendment that did only so so in the soil at Monroe. Next up was the Tagro, and coming in third was the biosolids compost. In the richer soil from City Soil Farm, the results for the biosolids compost that we had tested in the field version of the study were similar to the results that we saw in the field. A little less kale than you got from fertilizer. However, both the Tagro and the vermicompost grew the same amount or more than the fertilizer. The results for plant nutrients were again all over the map (Una et al., 2022).

Here the results made much more sense (Figure 1). For the plants grown in the Tacoma soil, all of the organic amendments made a huge difference. Kale Caesar versus no Kale Caesar. Portion size varied by amendment. The highest yield was in the vermicompost — the very same amendment that did only so so in the soil at Monroe. Next up was the Tagro, and coming in third was the biosolids compost. In the richer soil from City Soil Farm, the results for the biosolids compost that we had tested in the field version of the study were similar to the results that we saw in the field. A little less kale than you got from fertilizer. However, both the Tagro and the vermicompost grew the same amount or more than the fertilizer. The results for plant nutrients were again all over the map (Una et al., 2022).

The take home for me from the field and greenhouse study is that it depends. If you start with a really poor soil, or fill material that someone wants to pass off as a soil, any type of organic amendment will be a big step up. However, as we saw in the richer soils, not all amendments are created equal. With biosolids as the primary feedstock, the biosolids compost had much lower yield than the biosolids blended into a potting soil. The vermicompost made from food scraps used in the greenhouse trial had higher yields than the Tagro biosolids potting soil. In a previous study, the locally produced food/yard waste compost lagged way behind the Tagro (Batjaika and Brown, 2020). The point is that not all amendments made from food scraps are equal.

If you are in the business of making compost or making a potting soil blend with your biosolids, feedstocks and quantities matter. The best way to avoid having to add that caveat “results may vary” is to do extensive recipe development and materials testing before you go to market. I’ve talked about this before. The results from this study are just another example of this. The same way we prefer one recipe over another — it appears that the plants do too.

Sally Brown, BioCycle Senior Adviser, is a Research Professor at the University of Washington in the College of the Environment.