Top: Compost from the food waste program at the Washington Corrections Center in Shelton is used to grow flowers and vegetables (above). Egg-laying chickens (left inset), which feed on soldier fly larvae, have been incorporated into the program. The Center‘s food waste program is part of the Sustainability in Prisons Project (SPP). Student Felix Sitthivong holds SPP program materials (right inset). Photos courtesy Sally Brown

Sally Brown

Sally Brown

It wasn’t just the worms that were grieving when the Washington State Department of Corrections (WA DOC) shut down the vermicomposting program at its facility in Monroe, WA. The program, which also included black soldier flies and Bokashi treatment of the food scraps generated in the prison, had benefited a large number of the men incarcerated at Monroe. Budget cuts and a declining prison population forced the closure. Thankfully, Nick Hacheney and Juan Hernandez, along with a number of the other worm stewards, were relocated to another prison in Shelton, WA. There, with the support of the WA DOC administration, they were able to start again.

Juan Hernandez holds his “Foundations In Composting“ class completion certificate and a chicken from the SPP at the Shelton facility.

A few visits in, I can attest that both the worms and the men are thriving at the Shelton facility. The food scrap program is being run under the auspices of the Sustainability in Prisons Project (SPP). That program strives to “empower sustainable change by bringing nature, science, and environmental education into prisons”. It seems that the food scrap program at Shelton is achieving those goals. The worm bins, Bokashi barrels and black soldier fly cages are now located in outdoor sheds. While they don’t have the same visual impact as when they were all in a single indoor space at Monroe, they are still able to process significant amounts of food scraps.

Vermicomposting was not originally in the WA DOC initiative, but began at Monroe Correctional and is now at the Shelton facility.

In addition, the bins, barrels and cages are now surrounded by functional spaces that complement their mission. Chickens have been incorporated into the program. The flock feeds in part on the larvae from the soldier flies. They are lavished with attention and their eggs are used inside and outside of the facility. The compost is used in part in the gardens that now surround the sheds. These gardens are planted in both flowers and vegetables. During my last visit I was led to a pile of zucchini recently harvested from the garden. Forget the delicate courgetti, these gardeners were going for size. The clubs may not have had the best flavor but the ability to grow something of that magnitude seemed to be the critical measure of success. In addition, a new native American garden was put in, where species that are culturally significant have been planted. The sweetgrass was thriving, as was the lavender and many varieties of sage.

Past BioCycle articles chronicle the accomplishments of food scraps management at Monroe Correctional and the Sustainability in Prisons Project in Washington State. Links are in the Additional Reading box at the end of the article.

Composting Class

Education has been incorporated into the vermicomposting program. Foundations in Composting is now a for-credit class that is taught in the facility. The textbook for the class was authored by Nick and Juan with some help from outside experts. It is available for use at facilities that express an interest. The goals of the class are as follows:

- Define basic principles and terminology used to plan, maintain, and use different types of compost

- Describe the physical properties of soil

- Summarize the benefits composting has on soil and plant health

- Design small and large-scale composting operations

- Compare and contrast various composting processes, alternative methods, and small and commercial-scale systems

- Apply mathematical principles to calculate appropriate nutrient levels, ratios of materials, and water content

- Analyze soil composition, chemistry, and health

- Explain the relationships between composting, the environment, and food waste

- Design a plan for a composting related project at a WA DOC facility

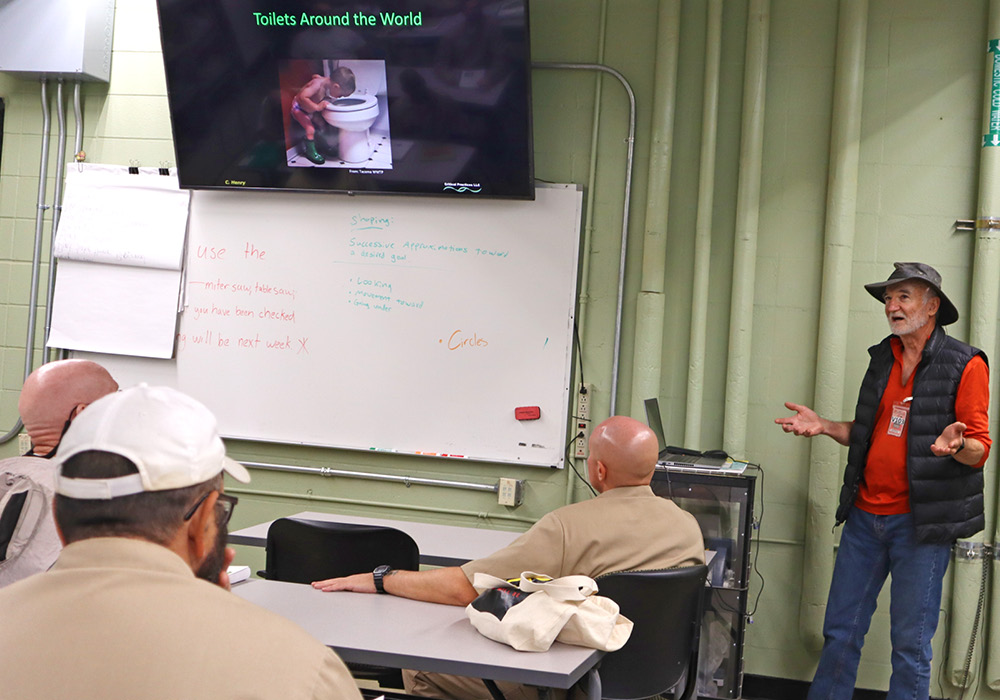

Students spend up to 35 hours in the classroom. Field work, including tending to the worms and the flies are a required part of the program. My husband, Chuck Henry and I recently taught a class for the second cohort of students in the program. A few weeks later we were able to attend the graduation ceremony for about 20 students. A third section of the class will be taught in 2025. It will be led by a new group of instructors. Nick and Juan are now working at the composting facility associated with the prison but outside of the prison gates.

The text is available for use in other facilities and a section has been taught at a prison in Nevada. One of the goals of SPP is to have programs like this — hands-on experience and classroom education — in prisons across the country. All facilities generate food scraps and all facilities have incarcerated folks who would benefit from this type of education. Washington State Department of Corrections has been trying to change the focus of its system from punishment to rehabilitation. A central component is treating incarcerated individuals as people. The vermicompost program, although started outside of this WA DOC initiative, certainly fits right in. The composting process is transformative, turning waste into a rich resource that fosters growth. Indications are that the program is doing the same.

Sally Brown, BioCycle Senior Adviser, is a Research Professor at the University of Washington in the College of the Environment.