Top: Conceptional visual depiction of crop farming scenario used in the EPA PFAS in biosolids risk assessment. Graphic courtesy U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

Sally Brown

Sally Brown

Writing about the latest biosolids risk assessment makes me think of the Isley Brothers’ “Work To Do.” People are just trying to do their jobs, the definition of which seems to vary widely. Biosolids managers and users are currently in a giant state of confusion and panic, not sure of how they will be able to continue doing their jobs or exactly what those jobs might be. Just a week or so before President Biden left office, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released a draft risk assessment for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in biosolids. There is a 60-day comment period, which ends on March 17, 2025.

Soon (pending congressional confirmation) to be second in command at EPA is David Fotouhi. Among other highlights, he is known for his previous work defending International Paper against PFAS related lawsuits. On the one hand, you have the EPA modeling risk for 1 part per billion of PFOA and PFOS applied to family farms and pastures. On the other hand, you have their soon to be boss with a track record of defending the company that poisoned the soils in Maine (Lerner, 2025).

Pathways Of Exposure

Let’s start with and focus on the EPA risk assessment. Because our poop is a reflection of who we are, it contains the wide range of chemicals and microplastics that we are exposed to. You can find caffeine, drug residues, microplastics and PFAS in poop. Prior risk assessments have been done for chemicals and metals that came from industrial sources. Dioxins, PCBs, lead and cadmium are a few examples. Controlling the concentrations of those into treatment plants was pretty simple. Identify the source and require them to reduce concentrations in their discharges or find another sewer to call home. Look as hard as you can but it is very rare that you’ll find dioxins or PCBs in human waste for all but an unfortunate few.

That approach can also be done for PFAS and has been done effectively, as explained in my November 2024 column in BioCycle. By doing just that the State of Michigan lowered PFAS discharges by 85% in four of six plants identified as high in PFAS (MI EGLE, 2022). That leaves domestic sources as the primary culprit (Lin, 2024). If the PFAS coming into most plants is coming from people’s homes and their tuchus, there is a high chance that exposure in those homes will be far greater than indirect exposure through biosolids application to soils. But the risk assessment task had been described by EPA and the work had to be done.

The EPA risk assessment identified a few pathways to study in detail. One involved a family living on a farm that was their source of fruits and vegetables. The farm comes equipped with a pond where they get their fish and a portion of their drinking water. Hopefully they boil it first. They drink groundwater from their well and their kids occasionally chow down on some soil. The other farm that they modeled also came with a pond and also included drinking water from the pond and a well. Here however, the broccoli came from the supermarket. The cows and the chickens, providing eggs, milk and meat, were the focus, with the animals feeding on forage grown on the farm.

In an effort to be conservative, each family lived on the farm for 10 years and only drank a portion of their water from the well. Each farm had had 400 metric tons of biosolids applied (about 250 tons/acre or 40 to 50 years’ worth) before they moved in. That biosolids contained 1 part per billion (ppb) each of PFOA and PFOS. Those are exceptionally low concentrations.

The Translation

Let’s put that into some perspective. A recent study measured wastewater influent, effluent and biosolids from plants in the San Francisco area where 80% of the flows are from homes (Lin et al., 2024). The authors used the TOP (Total Oxidizable Precursor) assay — a way to test for versions of PFAS that have the potential to turn into PFOS and PFOA in the wastewater plant or in soils. The results from this extraction don’t mean that they all will turn into PFOA or PFAS. It means that there are a bunch of different types of PFAS that might make that transition.

A recent study measured presence of PFAS in wastewater influent, effluent and biosolids from plants in the San Francisco area where 80% of the flows are from homes. Photo by Azita Sayadi

The TOP assay showed that influent from residential sources was almost as high as the highest measured source — an industrial laundry. A portion coming into the plant ended up in the biosolids. The mean PFOA concentration in the San Francisco biosolids measured 2.63 ppb (0.5-14.7) and the PFOS measured 13.8 ppb (beyond detection is 49). The top 6 inches of soil weighs about 1,000 tons so adding 250 tons of biosolids to it (the quantity modeled by EPA) would dilute those concentrations by 75%.

The EPA used the data that was out there to come up with the different risks associated with all of the activities those farm families could do to cause harm. With the exception of doing laundry, eating take out or sitting on their sofas. They found that there were risks. Here are their biggest concerns:

- Drinking milk from the majority pasture-raised cows consuming contaminated forage, soil and water

- Drinking water sourced from contaminated surface or groundwater

- Eating fish from a lake impacted by runoff from the impacted property

- Eating beef or eggs from the majority pasture-raised hens or cattle where the pasture has received impacted sewage sludge

The risk assessment included drinking milk from majority pasture-raised dairy cows. Photo by John Haynes, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons (cropped and manipulated by BioCycle).

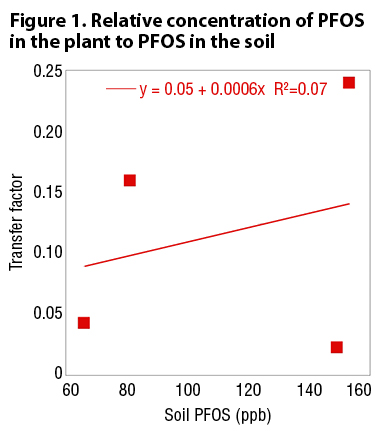

The problem was, in part, the data that they used. For uptake of PFAS into forage grasses, they relied on a single study that was done on fields where the biosolids were highly contaminated because the treatment plant accepted discharges from the 3M factory that made the PFAS (Yoo et al., 2011). They alluded to another study, done on farms in Maine where biosolids or pulp sludge that had received influent from coated paper production had been applied (Simones et al., 2024). At the one farm where there was a single source of PFAS they set up a field trial. One farm, one historically contaminated source. Across the different plots the soil PFOS concentrations varied from 55 to 153 ppb. The authors calculated a transfer factor or the relative concentration of the PFOS in the plant to the PFOS in the soil.

This was the basic number that EPA used to estimate risk. On the single farm with the single source, that transfer factor ranged from 0.021 to 0.4 (Figure 1). Not exactly what you would call narrow or precise. In fact, the whole exercise is characterized by insufficient data, typically taken from worst case historically contaminated sites. When I am talking contaminated here, I am not referring to discharges from industrial laundries. Instead, I am talking about from historic manufacturing of products that contained excessively high (not seen today) concentrations of PFOA and PFOS.

This was the basic number that EPA used to estimate risk. On the single farm with the single source, that transfer factor ranged from 0.021 to 0.4 (Figure 1). Not exactly what you would call narrow or precise. In fact, the whole exercise is characterized by insufficient data, typically taken from worst case historically contaminated sites. When I am talking contaminated here, I am not referring to discharges from industrial laundries. Instead, I am talking about from historic manufacturing of products that contained excessively high (not seen today) concentrations of PFOA and PFOS.

What Happens Next?

No one knows what is going to happen next. Will this be ignored or will there be a subsequent process to set limits? Will peer review have an impact? In the midst of this chaos some states are proactively considering banning land application. Others are making their own limits, primarily following the sensible approach used in Michigan. In the middle of this uncertainty, people keep flushing. The treatment plants keep operating and making more biosolids. There is work to do.

For biosolids programs and the farmers that rely on them, work has entailed using biosolids instead of fertilizers to grow crops. This practice has been studied and studied again and been shown to raise yields and soil carbon. I’ve argued that wastewater treatment plants (now often referred to as Water Resource Recovery Facilities or WRRFs) are true outposts of environmental stewardship. Using biosolids instead of synthetic fertilizer is a great way to also promote soil health and sustainability.

The authors of the EPA risk draft were doing their job within very narrow constraints. They had limited data and a rigid structure to follow. Even though they state repeatedly in the document that the primary source of PFAS at the levels that they were modeling was domestic influent, their task orders prohibited them from calling out the obvious. Domestic influent is the industry term for your house. In other words, the potential for exposure to PFAS in your house is orders of magnitude higher than any risk described in their document. And finally, we have a new second in command at EPA who has chosen to forget that the ‘E’ at the start of the agency name is Environmental and has seemingly chosen to replace it with an ‘I’ for Industrial. It seems that these various jobs will be far from complementary. But as the Isley Brothers put it many years ago:

Oh, I, I got work to do

I got work baby

I got a job baby

I got work to do, everybody’s got work to do

Sally Brown, BioCycle Senior Advisor, is a Research Professor at the University of Washington in the College of the Environment.