A Massachusetts trash hauling and recycling company invested in a mechanical separation system for food waste, opening up outlets for the processed material.

Bob Spencer and Morgan Casella

BioCycle May 2017

Storage area for packaged dry foods such as bread and cereal, to be loaded into the Scott Turbo Separator, and recovered for animal feed. An entire pallet of packaged food, inside a large cardboard box, can be tipped into the hopper for processing. Photo by Bob Spencer

“We had hoped one of our composting partners would have made the investment, but they were not convinced there was a consistent supply of packaged food to justify the investment,” notes Harvey. “We toured the Exeter Agri-Energy anaerobic digester (AD) facility in Exeter, Maine, which has a Scott Turbo Separator, and were impressed with the capabilities of that machine to remove packaging, and produce a slurry acceptable to the AD facility.”

E.L. Harvey operates a comprehensive recycling facility at its site in Westborough, including a transfer station where food waste is consolidated into larger loads and taken to several composting facilities, as well as a construction and demolition debris processing plant, a single stream MRF, and an asphalt, brick and concrete crushing operation. However, its permits from the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) do not allow on-site composting, so collected food waste and yard trimmings have to be transferred from this site.

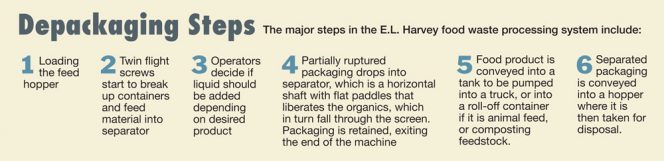

To process packaged and/or contaminated food waste streams, E.L. Harvey invested in the largest of three Scott Turbo Separator models, the T42. The system includes a feed hopper, twin-screw conveyor, stand and work platform, the separator, and a discharge conveyor. It was installed in late fall 2016 in an enclosed area next to the trash transfer station. Approximately $400,000 was invested in the equipment and system installation, and at the time of a tour in early March, the unit had about 250 hours of operating time. On average, E.L. Harvey is processing about 100 tons/week through the separator, which has the capacity to process 18 to 20 tons/hour.

Recycling Outlets

The company is able to prepare the food waste it processes for the most appropriate recycling outlet, which include animal feed, slurry for anaerobic digestion, and a semisolid material for composting. “Our location in central Massachusetts allows us to recover packaged food waste through the Scott Turbo Separator and we have been shipping it to anaerobic digesters located in Rutland and South Hadley, Massachusetts, with most going to the Exeter, Maine facility,” explains Harvey. “Our experience has been that the AD facilities are not always available to receive food waste due to many factors, and therefore, we can also produce a drier slurry that is hauled to composters, or we can produce a product that goes to a local company that makes animal feed.” He adds that E.L. Harvey is working to establish a value for the material, but at least it is not paying a tipping fee when sent to feed.

Twin screws in the bottom of the feed hopper (left) tear open cardboard boxes and other containers while conveying the contents to the separator. Access doors on the separator (right) allow removal of material that may jam the internal paddles, and enable entry for cleaning, maintenance, and adjustment of the screen and paddles. Photos by Bob Spencer

Food packaged in glass bottles and jars is not processed since the pieces of broken glass will contaminate the product. “We saw a separator in Minnesota that was processing products packaged in glass, but the final material contained too much glass for the composters and AD facilities we work with,” explains Harvey. “We also do not process frozen foods since they are too hard for the equipment to break apart, therefore we have a bin where we thaw frozen food before introducing into the equipment.”

Harvey estimates that residual packaging separated from the food is approximately 10 percent of the input by weight, and is generally not acceptable for further recycling due to contamination with food waste. It would require additional cleaning/drying to make it suitable, something that is not economically viable at this time.

Currently, two people operate the separator, one to load the hopper and manage the output, and another to operate the separator, which involves adding the appropriate amount of liquid, and making sure the separator is not overloaded (see Box). The amperage on the Turbo Separator shaft is closely monitored in order to not overload the unit. As amperage approaches levels that indicate clogging may occur, the operator backs off the infeed rate of the twin flight screws. Harvey notes that clogging of the unit at various points has been an operating issue, but they are getting more experienced at preventing jams in the conveyors and screw.

He adds that the unit works well with consistent feedstocks, particularly yogurt, soup, potato chips, and salad dressing, and yields excellent energy sources for the AD plants. One pallet of packaged yogurt typically weighs about 1,600 pounds. To reduce operating costs, the company plans to use recycled wash water from a large industrial washer used to clean Totes as make-up water for the separator.

Since E.L. Harvey has a MRF, a decision has to be made whether a large cardboard container is worth the time required to remove the contents before loading into the hopper. Generally, the entire pallet is tipped into the hopper so the cardboard is not recycled.

Residual packaging consists primarily of cardboard, plastic containers, and film plastic, and is typically too commingled for further recycling (left). Tanker trucks (right) are parked adjacent to the separator so liquid food waste can be loaded for transport to AD facilities in Maine and Massachusetts. Photos by Bob Spencer

Future plans include installation of a 20,000-gallon storage tank for the liquid destined to AD facilities, which will allow tanker trucks to be filled when they pull in rather than have a truck parked for a number of days until a full load can be produced.

Harvey points out that in order to take advantage of the processing capacity of the separator, it will be important for MassDEP to continue education and enforcement of the organic waste ban to the food manufacturing and distribution industry.

Bob Spencer is a Contributing Editor to BioCycle. Morgan Casella is with Dynamic Organics.