Top: Food scraps are collected from households and juice bars and composted at Sustainable Community Farms in Detroit. Photos courtesy Michelle Jackson

Neil Seldman

Detroit, Michigan households generate 240,000 tons of garbage annually. The city (pop. 620,376) pays an estimated $200 million to private haulers to collect and dispose of these materials, supported, in part, by a per household annual fee of $240, which is scheduled to increase to $300 over the next few years. The households and the city get little in return for this outlay. Yet these materials are not considered waste until someone decides to waste them. In fact, they are materials upon which to build a vibrant network of recycling, composting and reuse that can, at once, yield economic, environmental and social benefits sorely needed in Detroit.

Across the country, policies, programs and enterprises are demonstrating that Zero Waste is an ample substitute for dumping materials in landfills or burning in incinerators. Zero Waste is creating good jobs, tax paying businesses, reducing recidivism, and reducing the global impact of cities and counties. Detroit can readily do the same, at the same cost as the city is now paying for wasting its wealth.

Detroit’s Waste Management Landscape

The now closed Detroit Resource Recovery Facility was once the largest trash incinerator in the U.S.. Photo courtesy Gyre, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons (cropped and manipulated by BioCycle).

In 2019 the largest waste incinerator in the U.S., the Detroit Resource Recovery Facility, closed suddenly. The city successfully transitioned to landfilling its waste. Now the challenge is how to reduce the waste stream flowing to landfills and monetize the materials through recycling, reuse, and composting.

Detroit’s residential recycling program is opt in: households have to request a recycling cart, and pay $25. To date, 40% of Detroit residents — or around 80,000 households — participate in curbside recycling. The city’s recycling performance doubled in the last few years, with the amount of materials recycled increasing from 4% to 8%. While encouraging, this is still below the state recycling rate of 21%, up from 14% since 2019 and the national recycling rate, 35%, which has been steady, some say stagnant, for the past 20 years. Detroit hopes to double its recycling rate again within the next two years.

To put these figures in perspective, large U.S. cities — New York, Houston, Dallas, Boston and Washington, DC — have recycling rates in the 20% to 25% range. Philadelphia reached 20% recycling only to fall back recently to 7%. Chicago is at 10%, Baltimore is at 15%. Other cities are doing better: Minnesota’s Twin Cities’ rate is 49%, Texas’ Austin is 42% and San Antonio is 36%, and Phoenix is 33%.

The anticipation that Michigan’s statewide recycling rate, as well as Detroit’s, are expected to continue moving upwards is due to State Law 115 and NextCycle, an innovative program for attracting and expanding companies that use recycled materials. State Law 115 passed at the end of 2022 and directs resources to increase recycling and composting. The Michigan Department of the Environment, Great Lakes and Energy (EGLE) recently announced that more Michiganders than ever have access to recycling services. Since 2019, the state has nearly doubled the number of households with available curbside recycling carts and drop-off sites. Nearly 3 million households — three-quarters of the state’s population — now have access to recycling in their communities.

Grants have been made to business and local government partners in communities across the state totaling over $7 million, more than Michigan has ever invested in recycling infrastructure and technology and far surpassing last year’s record $4.7 million. A recent survey sponsored by EGLE found that understanding of recycling best habits has increased in every corner of the state. EGLE leaders attribute much of Michigan’s improved recycling success to the state’s award-winning “Know It Before You Throw It” awareness push featuring the Recycling Raccoons Squad.

The NextCycle program is helping the development of new recycling, reuse and composting businesses in and around Detroit. To date, Keira Higgins, a NextCycle Program Manager, reports there are nearly 30 projects across southeast Michigan, 14 of which impact Detroit and Wayne County. These projects and businesses range from architectural salvage, tire recycling, textile recovery and repair, composting, and battery recycling, among other initiatives.

Composting: An Elixir for Urban Agriculture

Composting is a source of optimism for higher waste stream diversion rates in Detroit. No other city in the country is as well suited for developing an efficient nutrient cycle than Detroit. Remarkably, since 2013 when Detroit passed the Urban Agricultural Ordinance that legalized farming and communal gardening, more than 2,000 gardens and farms are believed to be operating in the city, including 1,433 family, 383 community, 120 school and 93 market gardens or farms (according to Keep Growing Detroit, August 1, 2023). The Detroit Land Bank, the largest property owner in the city, has more than 63,000 empty properties that are available to the public.

Organics comprise one-third of the city’s waste stream. There is a thriving decentralized network that operates and/or supports community composting sites in the city. These include Sustainable Community Farms, Zero Waste Detroit, FoodPlusDetroit, local chapters of the Sierra Club and NAACP, Green Living Science, Recycling Here! and Detroit City Council’s Green Task Force. Deborah Stewart Anderson heads up Zero Waste Detroit, which fought for decades to shut down the incinerator. She also served as recycling Education and Outreach Coordinator under contract with the city. “We need to emphasize how recycling and composting information and public awareness can be combined for greater effectiveness among school children and families,” notes Anderson.

The plan for citywide composting is compatible with backyard composting, which can remove 10% to 15% of a household’s waste generation from disposal. FoodPlusDetroit, an accelerator of community projects that build Detroit’s capacity in all sectors of the food system, helps homeowners start composting. Its “People’s Compost Initiative”’ offers compost training and demonstrations for people of all ages.

The city’s grassroots composting movement is well represented by Michelle Jackson, director of Sustainable Community Farms. She sees progress towards composting as the City Council has begun to consider it, including the addition of “green” bins for each household for collection of source separated food scraps. At the same time, the Detroit Department of Public Works is coordinating new rules to govern the burgeoning grassroots composting networks in the city. Zoning and land ownership issues are essential to address to assure that composting operations can run smoothly without unnecessary burdens.

Jackson would like to accelerate the trajectory of composting by taking advantage of Detroit’s abundance of open spaces. The kernel of the concept is to collect clean source separated food scraps from households by bike trailers and vans and process the material into finished compost (and related compost products such as vermicompost and liquid soil amendments) in the very District where they were collected. This saves on route collection and transportation time and labor and provides an ongoing source of invaluable topsoil for urban agriculture. Finished compost would be distributed to Detroit’s farms and gardeners in exchange for data on how application of compost materials impacts agricultural yields, explains Jackson. Federal programs can provide the capital for the necessary infrastructure, while operating funds will be generated by business activity.

Sustainable Community Farm operates a food scrap composting facility on a city block that only has one house. The composting parcel is 60 feet by 200 feet. “We utilize static piles and only accept vegetative food scraps,” says Jackson. “Funding from a Robert Wood Johnson grant enabled us to establish this site about four years ago.” Some residents in the neighborhood drop off their food scraps, but most are collected via buckets distributed to participating households and some juice bars. Material composts for 8 to 12 months and then is sifted by hand. “Some people prefer to take the compost unscreened and then continue to cure it prior to use in their gardens,” adds Jackson.

To sustain the program after the grant expires, Sustainable Community Farms anticipates three sources of revenue: Tip fees from companies and government agencies that will bring their organic materials for composting; sale of excess finished compost and compost products; and shared savings resulting from the city diverting tons of material from the waste stream thus saving the city collection and landfill tip fees. For example, in Berkeley, California, the city pays Urban Ore, a materials management company, $41 for each ton its workers pull out of the waste stream for reuse and/or recycling. This is the same amount that the city pays to tip waste at a landfill. The city saves the cost of transportation and tip fees.

In Detroit this concept applied to composting would work as follows: Assume that the city pays $100/ton to collect waste and $100/ton to transport it and pay a tip fee at the landfill ($200 in total). The composting entity would earn 25% of this fee, or $50/ton, which would sustain the enterprise — thus rewarding both parties.

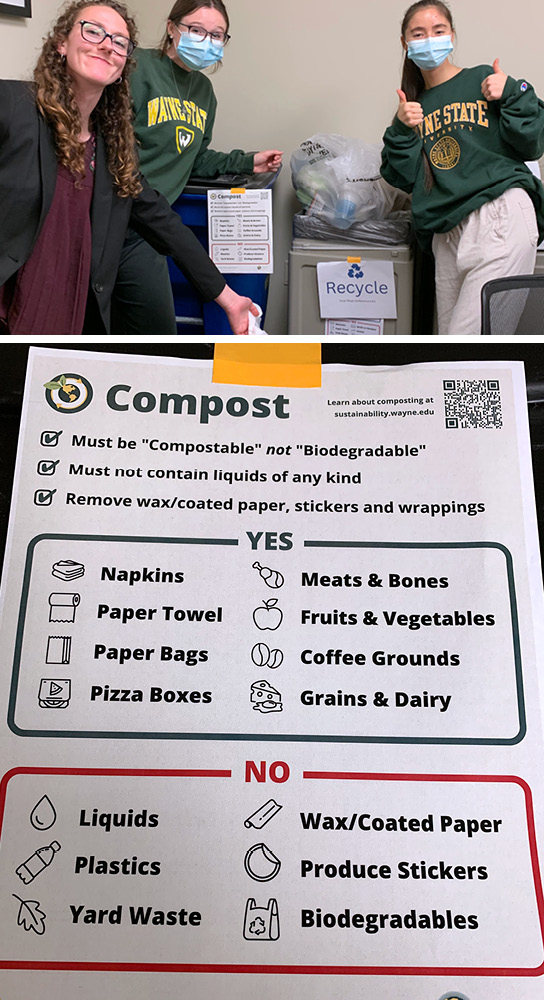

Students at Wayne State University collect and deliver food scraps from the campus to the Georgia Street Community Collective’s composting site.

Another community composter in Detroit is the Georgia Street Community Collective, which illustrates the braiding between nature, family and community. The Community Collective compost garden center was started by Mark Covington, who applied the skills he acquired growing up gardening with his grandmother to rescuing two vacant blocks on the East side of Detroit. Since 2021, the site has composted 50,000 pounds, or 25 tons, of food scraps from homes and Wayne State University’s food service. University students, known as the Compost Warriors, deliver 9 tons of food scraps annually through a project facilitated by Food Plus Detroit.

The Collective produces over 35 varieties of vegetables and spices — from tomatoes, peppers, and okra to watermelon, cayenne, kale, broccoli, eggplant and more. “It is easier to let you know what we don’t grow than what we do,” says Covington. Finished compost is applied to the garden soil and increases yields. Produce from the garden is made available to neighbors through a “free refrigerator” maintained at the garden. Overall operations involve 150 volunteer neighbors — 120 in the garden and another 30 in composting.

Neil Seldman, PhD, has been a student of Detroit’s solid waste management since 2007 when he became a founding member of Zero Waste Detroit. He is a nationally known expert on recycling and local business development. He is also co-founder of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, the National Recycling Coalition, Zero Waste USA, Save the Albatross Coalition and the International Zero Waste Alliance.