Environmental center’s Food Cycle SD creates an exchange to “upcycle” surplus food to people, animals and as necessary, organics recycling.

Marsha W. Johnston

BioCycle December 2015

For over 30 years, the Solana Center for Environmental Innovation, formerly Solana Recyclers, has pioneered waste reduction initiatives in San Diego County, California. Over the last couple of years, as California increased its focus on organic waste diversion from landfills, and national attention to the monumental food waste problem gained momentum, Solana’s Executive Director Jessica Toth saw an expanded role for her organization.

“We saw the need, where the supply and demand of surplus food were not meeting each other,” says Toth. “After hearing from many groups that either want to discard or use organic material, we developed the concept of an organics exchange/clearinghouse, which we’re calling Food Cycle SD.”

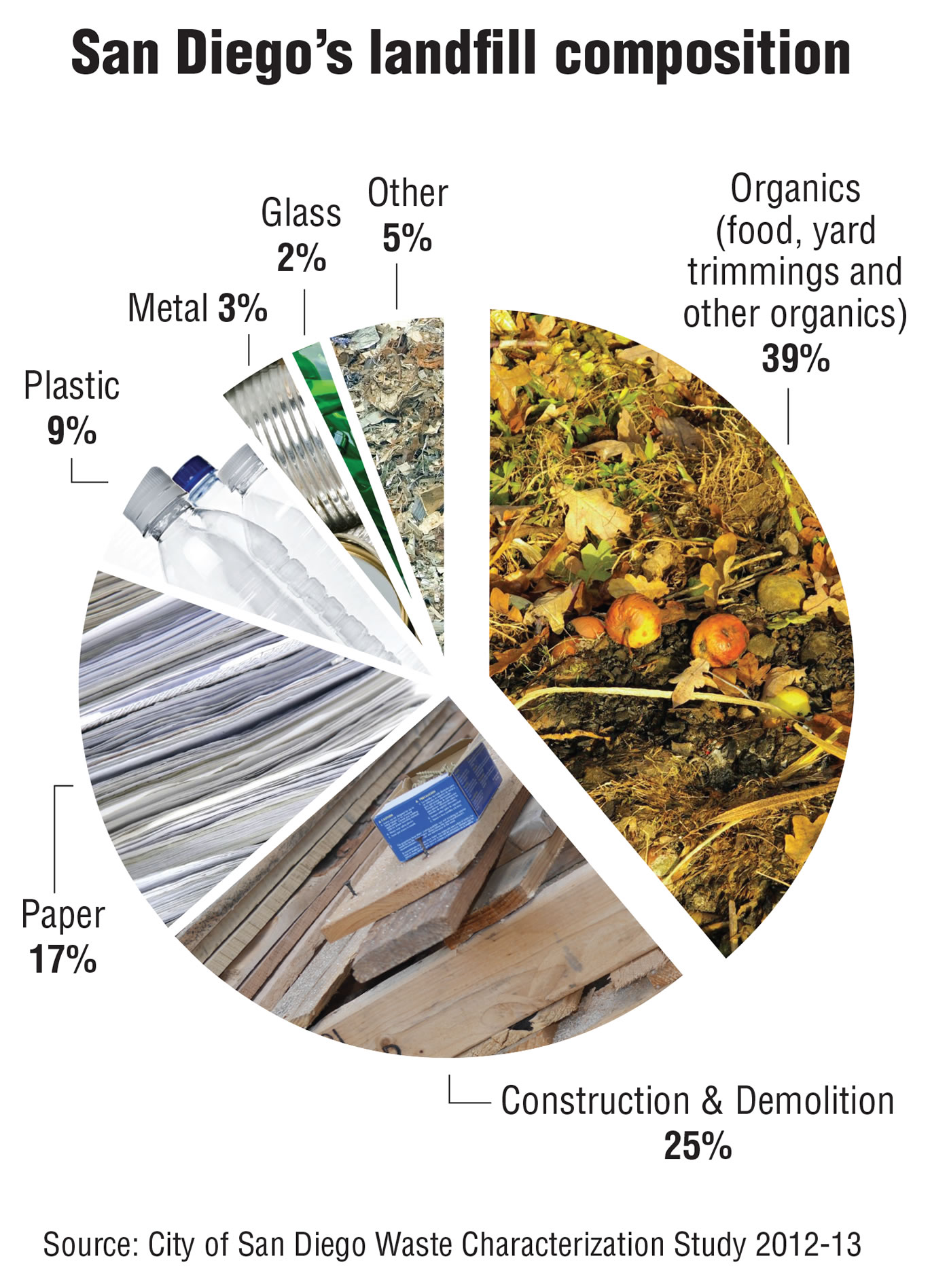

A recent Landfill Waste Characterization Study for San Diego County showed that “edible and compostable” organic waste was the largest single category, at 39 percent, or roughly 500,000 tons, while authorities estimate that they need only 46,000 tons to end hunger in San Diego County. According to Feeding America San Diego, 480,000 San Diegans live in food-insecure households and one in five children in San Diego County are at risk of hunger. For Toth, all of that food should be upcycled, in the following order: Feeding people, feeding animals, creating biofuels and other industrial uses, and composting.

“Feeding people in need is not a food shortage problem, but a networking and logistics problem,” explains Toth, adding that with its unique geography that boasts close proximity of agricultural, commercial and residential areas, San Diego County presents a

high number of potential outlets for both animal feed and composting. In fact, the county has 5,700 small farms, the highest number in any county in the country, according to the San Diego County Farm Bureau, not to mention a world-class zoo and wild animal park.

On the flip side, San Diego County, with 19 jurisdictions managing a population of 3.2 million, does not have a commercial composting facility with enough capacity to meet the need for turning nonedible food waste into compost. “If you’re within San Diego City boundaries, a small number of businesses, such as the University of California San Diego and the Convention Center, can divert their food waste to the City of San Diego’s Miramar Greenery, but it does not have the capacity to meet the County of San Diego’s needs,” notes Toth. The nearest facility with capacity for food scraps, she adds, is in Victorville, 135 miles away.

Food Cycle SD

Toth saw the opportunity for Solana Center in precisely the combined lack of a commercial composting facility and the County’s unique geography. “The fact that we don’t have a one-size-fits-all solution in San Diego County is actually good news for the environment,” she says. “That would make it too easy to just put food scraps in a bin and have it ‘go away’. We have to look at the highest and best uses because we don’t have a solution.”

For example, the Center’s food waste audits have prompted companies to change their practices. A local kosher kitchen was certain that it generated little food waste until a week-long audit showed 80 gallons a day were produced. “That caused the establishment to do some source reduction, such as not cutting up a bunch of lemons as garnish and then throwing the unused ones away,” notes Toth.

As a prelude to officially launching Food Cycle SD, over the last year, Solana Center has conducted both pre and postconsumer organic waste upcycling projects to demonstrate how the county’s unique characteristics can facilitate the best uses for excess food. A six-month preconsumer project, which ran from November 2014 to April 2015, began when the regional manager of a large national fast food chain asked Solana Center to help divert food scraps from its new store in Encinitas. “We are contacted by people because they know we provide composting education,” explains Toth. “In many of this fast food chain’s other locations, they have a channel for the preconsumer food waste.” Its preconsumer kitchen food scraps stream was comprised of extremely clean, inedible food, such as onion skins, potato peels, lettuce ends, and bits of tomato.

Six month pilot with a fast food chain restaurant captured preconsumer kitchen scraps comprised of clean, inedible food such as onion skins, potato peels, lettuce ends and bits of tomatoes. Photo courtesy of Solana Center for Environmental Innovation

Solana Center used the online exchange site Freecycle.org to advertise that it had 3 cubic yards per week of consistent produce scraps for any appropriate need. “We got a petting zoo that wanted it for animal feed and Coastal Roots Farm, a 67-acre organic farm that is 0.8 miles away, which needed soil amendment,” she says. The farm was purchasing expensive loads of finished compost, trucked in from the San Pasqual Valley, 25 miles away.

Solana Center engaged the existing waste hauler, EDCO, to take the fast food outlet’s scraps. “For EDCO, it was not cost effective,” notes Toth. “The hauler agreed to participate in the six-month pilot to test the concept.” She adds, however, that some San Diego County areas have franchise agreements, so the named trash hauler has to be part of the solution, as it, like EDCO, has the monopoly on “waste” leaving a serviced premise. The pilot illustrated that moving organic material from generators to end users is a logistically messier Point A-to-Point B process than is picking up from multiple places and hauling to a central station, and that it “starts to eat into the [hauler’s] margins.”

At the end of the six-month pilot, participants had diverted 53 cubic yards of food scraps, or the equivalent of 29.7 metric tons of CO2e emissions avoided. Coastal Roots Farm had two people managing the composting part-time and determined that the compost they made with the food scraps was four to five times more nutrient-rich than what they had been purchasing.

The fast food organics generator saved $250/month and found that its training costs were negligible. According to the food chain’s own report, “The program was rolled out during the regular crew meeting and follow-up consisted of a notice posted in the break area. Aside from forwarding [Solana Center’s] email reports and two follow-up phone calls, we achieved our success rate with no other effort.”

Despite the positive outcomes, the farm had to discontinue taking the food scraps as it is not permitted as a composting facility. Solana Center is working at the local, regional and state levels to see what can be done to permit mid-scale composting facilities. For example, because the farm is in a special agricultural zone, Solana Center requested that the City of Encinitas accept the project as being in conformance with permitted uses within the zone.

Postconsumer Pilot

The postconsumer pilot occurred in July 2015 during the annual Switchfoot Bro-Am beach concert and surf contest. The one-day event draws approximately 15,000 people and presented a prime opportunity to partner with the Rob Machado Foundation to further educate people about waste. In previous years, Switchfoot consistently diverted just over half of its total waste through standard recycling. “In the past, we did not include a food waste stream because we didn’t know how to handle postconsumer food scraps,” explains Toth. The diversion rate, with only recycling and trash options, was not able to get above 60 percent. Last year, for example, the event generated over 1,500 pounds of waste and 57 percent was diverted from the landfill through recycling.

Food Cycle SD conducted a postconsumer food scraps collection pilot at the one-day, annual Switchfoot Bro-Am beach concert and surf contest. Photo courtesy of Solana Center for Environmental Innovation

This year, the organizers and Solano Center decided to add a food waste stream and to use the Bokashi technique, a closed, in-vessel method of collecting food waste. “Bokashi” is a Japanese word meaning “fermented organic matter.” The technique combines organic wastes with any fine organic grain or grass-like medium, e.g., bran, rice, wheat mill run (a waste product from flour milling), used mushroom substrate, dried leaves and sawdust. The material is inoculated with beneficial microbes that flourish in anaerobic, acidic environments but smell less foul than do those in unfettered, natural anaerobic conditions.

Solana Center used 55-gallon industrial food-grade containers with locking lids along with inoculated spent barley grain from beer-making, and got authorization from the county to collect material at the concert and manage it at the Center. “The benefit of Bokashi for us was that we could take all of the postconsumer food scraps,” says Toth. With the aid of 100 volunteers who sorted through trash at 30 stations and educated visitors, as well as shout-outs from the band, this year’s event nearly doubled the total amount diverted to 2,923 pounds, of which 83 percent was either recycled (1,628 pounds) or fermented (785 pounds of food). The collected food scraps were transported to Solana Center, less than three miles away, where they fermented with the Bokashi-inoculated grain for two weeks. Then they were dumped into one-foot deep troughs in on-site garden beds and covered with soil. An intern conducted a study comparing irrigation needs on a Bokashi-incorporated bed and a control bed. She found that 41 percent less water was required in the Bokashi bed.

While the postconsumer pilot was hugely successful, Solana Center considers preconsumer organics to be the low-hanging fruit. “It’s a straightforward opportunity because, for the most part, it’s uncontaminated, abundant, readily compostable, but also good for animal feed,” explains Toth. Solana Center has “long lists of potential partners” to help proceed, but is currently seeking funding from foundations “interested in food issues.” The San Diego County Board of Supervisors has already provided the Center seed funding to help connect participants. It also is working closely with the well-organized San Diego Food System Alliance to address the very pressing need to feed the hungry. “First and foremost, when we identify edible foods going to the landfill, we must connect food-generating businesses with food recovery agencies,” she emphasizes.

Given the lessons learned from the two pilots, Toth adds the most pressing needs Food Cycle SD must meet to ensure smooth operation include:

Relaxed state-level restrictions on importing food scraps. Solana Center is working at all levels with organizations like Californians Against Waste to change regulations and incentives for diverting organics from the landfill. “We’ve proposed giving a tax credit to organics-generating businesses that divert from landfill,” she says.

More incentives to “donate” food scraps “in good faith” for all types of end uses. These include three- and four-way long-term ongoing partnerships, established using technology and speed dating-type events.

Consumer education. “The biggest barrier to making all of this diversion happen is not regulatory but education,” notes Toth. “The other part is connecting the supply and demand of surplus food, and that is the role we want to play.”

Marsha Johnston, principal of Earth Steward Associates, is a Contributing Editor to BioCycle.