Prince George’s County, Maryland began a food scraps composting pilot using a covered composting system, and is processing about 125 tons/month.

Nora Goldstein

BioCycle May 2015

Food scraps, some arriving in compostable bags (inset photo), are unloaded onto a bed of mulch, then mixed in with a front-end loader. Photos by Steven Birchfield, Maryland Environmental Service

For almost 25 years, Prince George’s County, Maryland has owned and managed the Prince George’s County Organics Composting Facility (aka: Western Branch) in Upper Marlboro, which is operated by Maryland Environmental Service (MES) through an intergovernmental agreement. The facility processes leaves and grass clippings into a trademarked compost product called Leafgro™ which is sold for landscaping, erosion control and green infrastructure projects. It also processes Christmas trees, brush and small branches into mulch that is given away to County residents each year during an Earth Day event. “Leafgro is such high quality, it has been used on the White House lawn,” notes Marilyn Rybak, Prince George’s County’s Section Manager of the Recycling Section, proudly. Between yard trimmings composting and materials recycling, the county has been very successful in “recovering value” from its waste stream, and has pushed Prince George’s County to number one in the state for waste diversion, she adds.

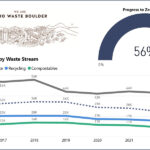

In April 2014, Prince George’s County hired SCS Engineers to conduct a waste sort of its residential and commercial streams. Food waste comprised 22.8 percent of the residential loads (yard trimmings were 7.3%) — the largest category by weight residentially. In the commercial stream, paper was 26.7 percent, and food was 26.1 percent by weight. “When we looked at that slice of the pie chart, we recognized a resource that could be captured instead of disposed,” says Adam Ortiz, Director of the Prince George’s County Department of the Environment. “The county’s landfill is slated to close around 2020, and to make the transition, we want to make smart policy decisions that are sustainable, economically and environmentally. Composting has been a real winner in both of those categories.”

The county decided to start a food scraps composting pilot at the Western Branch Composting Facility in May 2013. It selected Sustainable Generation LLC’s SG Mini™ System utilizing GORE Covers. The system includes three covers that can accommodate three 80-foot long by 25-foot wide positively aerated “heaps.” Up to 45 tons/week of separated food scraps from both residential and commercial sources are received, along with soiled or waxed corrugated and some paper products. Food Scrap Demonstration Pilot Project Partners include the University of Maryland (UMD), the cities of University Park and Tacoma Park, and several commercial haulers — Apple Valley, Progressive Waste Solutions and Compost Crew. Apple Valley brings in organics from Whole Foods Markets.

“Our model over the past few years is to partner as much as possible with other entities that can contribute to our common goals,” explains Ortiz. “Sustainable Generation brings a tremendous amount of expertise to the program, and partnering with UMD, the municipalities and Whole Foods has been working well. They are supplying high quality organics. And then we have our longstanding partnership with MES, and the many retailers that sell Leafgro products. Without all of those pieces working together, Prince George’s County would not have the success that we’ve had.”

Composting Logistics

The Western Branch Composting Facility is on a 200-acre site, of which 52-acres are paved asphalt. It receives between 55,000 and 60,000 tons/year of yard trimmings. Finished compost is screened to about three-eighth inch; roughly 45,000 to 50,000 cubic yards/year of Leafgro are produced.

About 165,000 households in Prince George’s County receive curbside yard trimmings collection on a weekly basis. For many years, yard trimmings could be set out in plastic bags, which became a significant litter challenge at the Western Branch site. “The plastic would shred during debagging or grinding operations and while the working area was fully netted, when placing the material into the open windrows, small pieces would go airborne,” recalls Rybak. “Not only would it blow on to neighboring properties, the shreds had the potential to litter the Western Branch tributary.”

Prince George’s County Council adopted a plastic bag ban for yard trimmings collection in November 2012, which became effective on January 1, 2014. It applies to the residential and commercial sectors. Yard trimmings in paper bags or loose in containers are allowed. Images illustrate sharp contrast pre- and

post-ban. Photos by Steven Birchfield, Maryland Environmental Service and Nora Goldstein

In November 2012, the Prince George’s County Council approved a plastic bag ban, which went into effect on January 1, 2014. “The ban applies to both the residential and commercial sectors,” explains Denice Curry, Senior Planner with the County’s Waste Management Division-Recycling Section. “We educated county residents and businesses about the ban via inserts in the tax bills, direct mail post cards, door hangers, press releases and fact sheets, as well as at community events. Yard trimmings had to be set out in paper bags or in a can or cart. When the ban took effect in January 2014, there was a three-month grace period to comply. Inspectors were equipped with door hangers to remind residents about the ban. Plastic bags set out after the grace period were tagged with a highly visible orange sticker and left at the curb for proper setout preparation. Residents and businesses did change their behavior, which is encouraging if Prince George’s County decides down the road that it wants to implement county-wide residential food scraps collection.”

Incoming yard trimmings are processed in a Peterson horizontal grinder, and then put into windrows, which are turned once a week with a Scarab turner. Water is added as necessary. The composting process takes 6 to 9 months, depending on weather conditions.

For the pilot, food scraps can be placed in preapproved compostable bags. MES builds a small windrow out of mulch, and then places about a foot of mulch in front of the windrow. Incoming loads are tipped onto the bed of mulch, and workers will pick out any contaminants that are in the food scrap stream. “We try to help our haulers help the generators to provide clean material,” notes Steven Birchfield, an MES employee managing the food residuals pilot program. “We invite generators to tour the composting site to see first-hand why keeping contaminants out of the separated organics is necessary.”

Because there are only three covers, MES currently composts in batches. “As a result, we must hold the food scraps until we have the correct tonnage,” adds Birchfield. After any visible contaminants are removed, the material is commingled with the mulch from the bed using a front-end loader. “We then cover the material with yard trimmings which act as both a biofilter and the batch recipe,” he continues.” Right before it is placed under the GORE cover, the material is ground to approximately 3-inch minus and mixed.”

The initial mix going into the covered system is about 50 percent food scraps and 50 percent yard trimmings. Once the heap is constructed, two front-end loaders pull the cover over the width of the pile. “It comes over like an accordion,” explains Randy Bolt of MES. Material remains under the cover with positive aeration for 4 weeks. Pile temperatures are about 165°F. After 4 weeks, the pile is uncovered, turned and covered again for 2 more weeks, after which the cover is removed and the material stays under positive aeration for a final 2 weeks for drying. Following the 8-week composting period, the compost is cured in windrows for 10 to 12 weeks.

For the food scraps composting pilot, the county selected Sustainable Generation LLC’s SG Mini™ System utilizing GORE Covers. Construction of a heap (left) and the covered piles are shown (right). Photos by Steven Birchfield, Maryland Environmental Service

The compost containing food waste is sold as Leafgro GOLD Blend. “It is a little higher in nitrogen than Leafgro, and the pH is spot on,” says Birchfield. “One of the users of Leafgro GOLD is the University of Maryland’s farm in Prince George’s County, which grows produce that is served in the dining halls. That is a true illustration of going full circle!”

Among the reasons Prince George’s County selected Sustainable Generation’s technology for food scrap composting was to evaluate how it could decrease the composting footprint at Western Branch. The pilot project has demonstrated that a smaller footprint is needed when using the covered system. “The Western Branch site can definitely accommodate expansion,” explains Rybak. “In fact, if we expand with a covered composting system, space will be freed up for management of other MSW.”

Prince George’s County is evaluating its next steps with regard to food scrap composting. “The goal is to expand the program substantially to meet the demand for food scraps diversion and to be a leader in the industry,” notes Ortiz. “We are getting demand from every angle — from municipalities, businesses and large institutions that are seeking an outlet for food scraps to the back end, where we sell out of Leafgro every year. We can’t put enough of the product on the shelves. Taken together, composting looks like a great growth industry for Prince George’s County.”